Gary Gillman, Beer Et Seq

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Following is an extract from Harry J. Boyle’s (1963) Homebrew and Patches, a memoir of farm life in 1920s and early-1930s Western Ontario. The book earned Boyle a Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour, one of two gained in his career, among numerous other honors. The extract describes in cinematic fashion the baked bean dish his mother made, indeed orchestrated in a family performance:

The baking of beans was a household project. Mother sorted the white beans, soaked them and brought up the big, gray crock with the heavy lid. We watched fascinated, when, after the long soaking, she put layers of onions and beans or smoked pork and beans in the crock and spread over them a magic potion of molasses, brown sugar, mustard and home-made chili sauce. The pot went into the oven in the quiet time after supper, the fire being tended with extra care that night. Soon a delicious odour permeated the house. I would close my eyes and imagine the rich, seething conglomeration inside the big pot. The aroma went to bed with me and got up with me in the morning. It haunted me at school and I hurried home to it with the teeth of the winter wind slashing at my cheeks and biting at my lungs.

We did the chores with a great burst of unprompted energy. Everybody, even Grandfather and Father, was washed up and ready, long before Mother had called us to supper.

This was the time when Mother was an actress. She set the plates and the knives and the forks with deliberate care. She surveyed the table setting, then vanished into the cellar, and returned with a special jar of pickles. She stacked dishes beside Father’s plate. She was maddeningly slow in spooning out the preserves. And just when we were certain she was going to call us to supper, she made another trip to the pantry.

Then the moment came. Mother opened the oven door, and, without being asked, we moved to the table.

“Here, let me heft that,” Father would say pulling on his old leather pullovers, and soon the great crock arrived on the bread board in front of his plate. The mixture was alive with the beans popping inside the tawny, reddish black crust on the top. From the warming closet on the stove came a pair of crusty loaves of brown bread. Our dinner was enough to give heart failure to a modern reducing faddist, but to us it was a feast fit for kings.

“You’ll burst,’’ Father warned me, ladling out more of the delight; and then as an afterthought, he spooned more onto his own plate, saying, “Guess I can’t see this go to waste”.

Grandfather puckered his moustaches in a fierce way and simply handed his plate. He didn’t want any comment. When it was full again and he had taken a piece of the still-hot bread, he stopped eating for a moment and stepped back into memory.

“The people that run down beans now don’t know what they’re talkin’ about. Why, when I was in the woods we lived on them. Had them four times a day.”

I left the table feeling that I had appeased the desire of a lifetime for baked beans. Just the same, near bedtime, there was another treat in store for me. Without attracting attention I slipped into the chilly pantry and made myself a cold bean sandwich. Nowadays, people shudder at the thought of it, but in those days cold beans with portions of meat and onion between two slices of bread and with a dab of hot “man’s” mustard was a delectable snack.

“You’ll have nightmares,” warned Mother, but she was secretly pleased with our craving for her beans.

I don’t remember having nightmares after one of these bean-orgies. My sleep may have been heavy, but it didn’t compare with the diet-conscious, induced nightmares of thirty years later.

Harry Boyle (1915-2005) grew up in a Canadian family, son of William Boyle and Mary Adeline Leddy Boyle (1893-1979).[1] Boyle’s paternal great-grandfather had homesteaded in early 19th century Ontario. He acquired land in St. Augustine, a hamlet not far inland from Lake Huron.[2] He built a log house that endured in Harry Boyle’s youth, used by then for storage and other miscellaneous purposes. Circa 1930, St. Augustine counted just 700 people. This and other biographical or related detail in these notes comes from Homebrews and Patches, also Boyle’s Mostly in Clover (1961) and Memories of a Catholic Boyhood (1973), further works of memoir. Together they paint a picture of his adolescence and education. Further biographical information on Boyle, and a bibliography of his work, are set forth in Kelly Burns’ entry in the (2011) Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 362: Canadian Literary Humourists, ed., Paul Matthew St. Pierre, p. 25 et seq.

After finishing high school, Boyle attended one year at St. Jerome’s Catholic college in Kitchener, Ontario, today part of the University of Waterloo. His studies and future at the college were continually impacted by a lack of money. Having sold a few short stories to Canadian and American magazines he made the decision to leave college for the working world.[3] Initially he worked in a labouring job, at a trucking firm where an alcoholic ex-newspaperman helped further his education.[4] Soon Boyle worked as a stringer for Ontario newspapers, and then for five years in radio broadcasting in Wingham, Ontario, a larger town near St. Augustine. Next, he spent a year in Stratford, Ontario as district editor for itsBeacon Herald. In 1942 he resumed broadcasting by joining the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in Toronto, enjoying a long career there. For the CBC he did farm broadcasts and later farm and general programming, as well as writing radio and stage plays.

In the 1950s he wrote columns of reminiscence for the Toronto Telegram, some of which were collected in the books mentioned. Having joined the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission in the late 1960s, he rose in the next decade to its Chairman, retiring in 1977.

Boyle died at 89, by then a nationally known writer and broadcasting eminence, quite a career arc for an Ontario farm boy. Mary Leddy Boyle’s presence and evident influence on Harry are constant and impactful through the memoirs. She was a full partner with her husband in running the farm, with distinct responsibilities assigned to each. Father handled all matters concerned with livestock, cows and pigs in this case, and dealt solely with the bankers who held the mortgage. Mother raised market vegetables from her garden and had charge of egg, butter and cream production, to augment the family income. Cash still was often short, the smallholder’s life ever parlous, and more so as Depression encroached.

The respective parental roles on the farm were typical for North American families in the period. In the writings of Boyle that we canvassed, neither he nor the mother express dissatisfaction with the assignment of roles. It does not appear Boyle or his mother considered her ambitions thwarted by conventions of the time. Rather, it seems each parent accepted their role as reflective of the natural and prevailing order in their world. In Memories of a Catholic Boyhood Boyle wrote:

H. G. Wells was [ca. 1930] urging the need for a world dictator. We didn’t know or really care about all this because the countryside and the village of Clover [St. Augustine] bore little relationship to what Marshall McLuhan today calls the “total electronic environment” Our environment was scarcely even mechanical, because the horse collar was still vital. Hard times were not such a visible factor as you might imagine. People didn’t mind saying, “We can’t afford it.” Collectively they felt they were lucky to live in the country…. This was the easy, casual life of our valley… [and] our nearest village, Clover. Everyone knew his place, and woe betide the stranger who came along to upset the even tenor of the village ways.

Boyle’s family, as appears from his books, was a sub-unit of an orderly, conservative community. Harry Boyle’s ambitions to write, and experience life outside the valley, departed to a degree from farm and village norms. The books suggest his mother wanted the family to live a conventional life, in tune with public expectations, in other words to maintain propriety in the eyes of neighbours and other actors in the valley, including the Church. The family attended Church weekly for mass, apart various special attendances including at Lent. Up to a point, mother was understanding of life’s realities as they impacted her children, provided the family’s image in the eyes of neighbours and local notables remained intact.[5]An instance may result from a story Boyle tells where mother required the lamp in the parlour to be turned high when his sister “entertained a beau”. Boyle explained:

Mother was constantly reminding my sister that it was indecent to turn [the lamp] too low on a Sunday evening. I have often wondered if she was as concerned with my sister’s morals as she was about what the neighbours might think if they saw only a faint glow coming from the parlour window.

Boyle describes another incident where it was mother’s turn to host a Women’s Institute function, which ended being ruined when the cow Brownie got loose in the house and gobbled some of the confections. Harry, and even father and grandfather, saw the humor in the situation more than she did. Mother was just starting to get over it when:

… the local paper decided to write a humorous article about it. Mother wanted to cancel our subscription as a result. Father said that cancelling our subscription was silly and tried to soothe her feelings by saying that the story hadn’t mentioned our names.

Mother was not consoled, noting it had been her turn to host the function, and everyone in town knew the story centered on her. In time mother’s hurt feelings ebbed and she would even pull the old newspaper account for a family chuckle.

Her teasing, orchestrated way to prepare and serve baked beans can be interpreted as allowing the family to enjoy a toothsome dish in a way that complied with expected public standards of behaviour. In a word, the family could enjoy her baked beans, but not too much. In that period taking a pointed interest in matters of the table was not a tradition, indeed culturally in the anglosphere. This entailed that one should not express overt enjoyment of food. See for example a lengthy account of contemporary dining customs in an 1885 New York Times article, which states in part:

…to take a serious view of eating is commonly considered in all Anglo-Saxon communities as the mark of a frivolous, if not depraved, mind… The Puritan looked upon a good dinner as a ‘snare’ and his descendants have retained the same view”. [6]

Mother’s play-acting can be viewed as ensuring food retained its proper place in the natural order: appreciated but not over-emphasized. Mary Leddy Boyle was training the children to develop an appetite for food that met societal expectations of appropriate, genteel if you will, behaviour Showing physical and verbal restraint when dining were hallmarks. This is underpinned by the way grandfather and father proffered their plates for a second helping. Father excuses his appetite, saying food should not go to waste. Grandfather, for his part, “didn’t want [to make] any comment”, yet clearly enjoyed his food, lapsing into memory how beans were a staple when out on logging expeditions in his youth.[7]

Also telling is the family took seats at table “without being asked”. They were avid for the beanpot to arrive, but mother delayed asking them to table to emphasize the ritual of dining, versus a “Come and get it, everyone!” approach. Boyle describes many other dishes in the book, e.g., an aunt’s herb-stuffed roast chicken as big as a turkey. His mother’s training ensured he would eat with decorum in such contexts, or at school, etc. Dining was not simply a matter for the home, just as the children entertaining their dates at home was not, or indeed Harry’s predilection for higher studies. Harry writes he tried to earn pocket money for his first year at St. Jerome’s College by delivering eggs and cream to local families for tips. He notes some customers observed tartly he was son of a family that could afford to send him to college, and refused to tip him.

In his un-Victorian way, by memorializing his family’s cuisine, Boyle did his part to evolve social mores in the 20thcentury.[8]

Mother controlled the household’s teapot bank, its cash reserve tidying the family over when barter was not possible, for example to pay annual taxes. She was a canny manager, insisting that “loans” from the battered vessel be repaid to keep the fund solvent. Boyle writes that at any one time only she knew the state of its accounts. From Mostly in Clover, this passage attests to his mother’s savvy management:

The teapot with the cream and egg money was scrutinized very carefully just before Christmas by Mother. She met the cream man and demanded the envelope before the family could get their clutches on the cash. She took the eggs to town and would not leave the cash balance as a “due bill” for the leaner months when cream and egg production slackened.

Despite the division of responsibilities with father, mother would stray occasionally into his realm, reminding him to visit the mortgage-holder when the year’s interest payment was overdue. The town’s bankers inevitably accommodated the family, sometimes accepting as payment a mix of money and goods, cut lumber, often. While a good manager she had an instinctive fear of “business”, considering that the parents’ ability to feed the family was anchored to staying on the land.

Boyle describes his discovery of books in a chapter of Mostly in Clover, “The World of Imagination”. He writes that reading and studies were viewed suspiciously in St. Augustine. After basic education the boys were expected to join the farm and ensure its succession. A teacher in the one-room St. Augustine school, probably detecting Boyle’s sensitivity and precociousness, gave him a copy of Kipling’s Captains Courageous, which he read multiple times over a blizzard Christmas. Then she gave him Black Beauty. With family influences to follow, this triggered a life-long immersion in writing and the arts. Initially, mother was not books conscious. Father and grandfather, even less so. However, seeing Harry’s unwillingness to give up books, rather than turn him against them they did the opposite, buying him more books. Mother started by giving him selections from Anne of Green Gables, which he read in his bed by stealth and candlelight. An uncle gave him an Edgar Wallace book. Father provided a boys’ annual-type volume. Harry soon amassed a shelf of books, and the interest burgeoned from there.

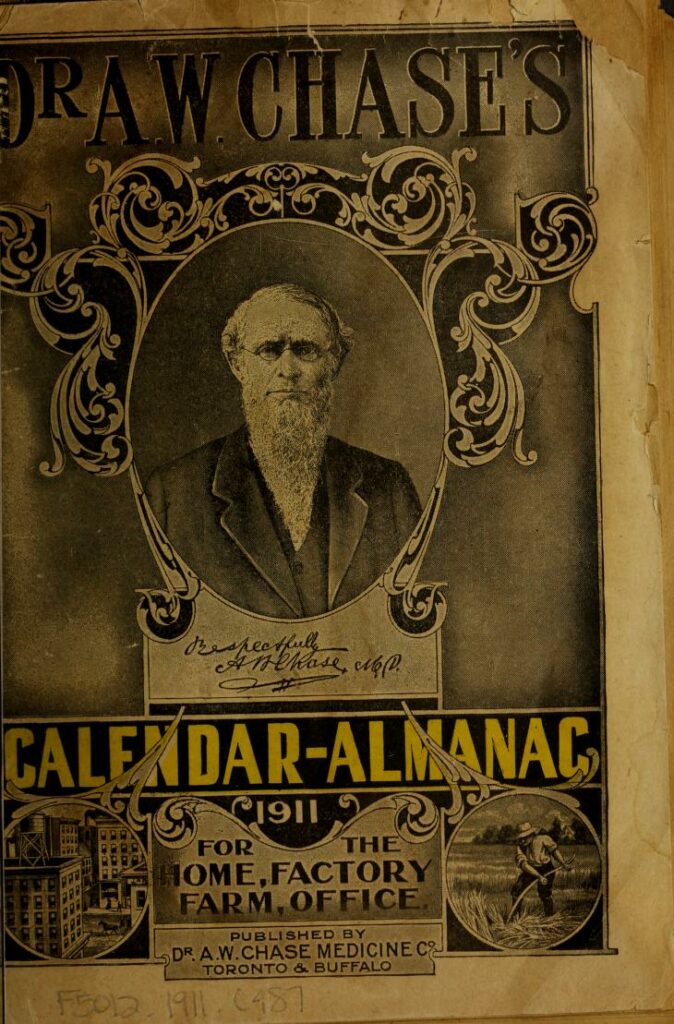

The parents started to read more as part of this process. Finally, the family read together, Silas Marner, say, this in the years before radio was introduced (a shape-shifting development in St. Augustine, Boyle explains). Boyle absorbed not just imaginative writing for his recreation, but also the almanacs the family regarded as totems for everything from weather prediction to knowing one’s fortune. Included in these notes is the cover of the 1911 Dr. Chase’s Almanac. In Mostly in Clover Boyle remembered:

… the almanac…was a great source of entertainment for us. I can still see the cover of it, showing the bespectacled and bearded face of Dr. Chase, hanging on the nail beside the newspaper rack whose fancy lettering proclaimed “Home Sweet Home.” On evenings when the wind dashed snow against the windows and drifted it against the door, the almanac came in handy.

It seems fair to infer that the parents’ own reading, especially mother’s, inclined them later to favour Harry’s further education, whereas absent that development, the vision to do so would have been lacking. This started with high school, viz. finding the money to send Boyle to Wingham’s “continuation school”, as it was called. He boarded in a musty rooming house during the week, returning home for weekends. The lodgings were rented by a Miss Havisham-type figure. Mother would pack him lunches meant to last the full school week, as each student had to provide his own larder. The supply inevitably dwindled toward the weekend, and probably Boyle’s memories of farm meals were sharpened by the extra appetite gained on reaching home Friday nights.

Boyle’s aptness for college was not in doubt: the real problem was money to pay for it. Finally, mother cashed a Victory Bond, given her at marriage and a precious family asset.[9] That sacrifice paid for one year’s college, a last resort. Church money was not forthcoming since in an interview with the local prelate Harry disclaimed having “the vocation”. A local politician, also canvassed due to Harry’s evident promise, proved equally unhelpful in the result. Mother agreed to use the bond money hoping, Boyle wrote, the Catholic environment of St. Jerome’s College would propel him finally to the priesthood, but Boyle implies she made the gesture anyway, realising he would never be a priest.[10] One can argue the maternal and affective side of her nature – the desire to see her son achieve his wishes and dreams of writing and a wider world – trumped finally her more conservative, conventional side. Boyle stresses she handed over the bond, it was her money that made the one year at St. Jerome’s possible.

When Boyle returned to the family after a year at St. Jerome, it was made clear there was no more money to fund studies at college. Father and grandfather told him he was unsuitable for farm work, a book lover usually is, they said. The only course open to him, therefore, was working outside the farm, which he did initially in Wingham, as mentioned. Still, his year at St. Jerome’s was an important “threshold”, as he put it, for a long career in writing, newspaper work and radio. He credits more though, in affecting language, the family hearth in St. Augustine.[11]

Mother’s key influences on him are manifest in the books. Not only did she gladden his interior through her cooking so resonantly recalled in his later years, she helped form the person he became intellectually and vocationally. In their way all the family did, comprising (as limned in the books mentioned), his father, mother, and grandfather, who lived with them.[12] In our estimation his mother’s influence was foremost. This results not so much from his express tribute but rather the ensemble of accounts and descriptions of Mary Leddy Boyle in the books. Not least was her gift to perceive and encourage his aptness to read more and for higher education, implying as it did a desire to know life outside the limits of the Boyle farm and village St. Augustine. The gesture gains additional poignancy in that quite possibly it foreshortened the family’s future in farming.[13]

Acknowledgement: many thanks to Assistant Professor Jennifer Helton for her good assistance to finalize the text of this blogpost.

Gary Gillman, August 2024.

[1] See the page for Mary Leddy Boyle at Find a Grave, which links to other family members including Harry Boyle.

[2] In these notes I use the real names of localities. Boyle used pseudonyms, for example Clover was St. Augustine.

[3] One story he mentions is “Revenge of the Hurons”, which an American magazine published. He writes in Memories of a Catholic Youth of his sensitivity (this in his teens) to the fate of the area’s Indigenous population, whom he calls “Huron Indians”, replaced on the land by the European pioneers. This is an early manifestation in Canadian literature of what is today a national pre-occupation, to reckon with the impact on First Nations (as termed in Canada) of the European arrival and settlement.

[4] Among reading the ex-newspaperman suggested were Thomas Babington Macaulay, Samuel Johnson and Sherwood Anderson.

[5] Instructive is a 1974 radio interview Harry Boyle conducted of fellow-author Alice Munro (much in the news lately as it happens). The tape has been streamed in the CBC archives. Alice Munro was raised in Wingham, where Boyle had attended high school and later worked in radio for years. Both writers traded notes on the importance of maintaining propriety in pre-war southwestern Ontario society, citing sexuality as an instance. Liquor prohibition (we are noting) is a further example, frequently addressed by Boyle in his books. St. Augustine was officially a dry area in the period he covers, but the prohibition was widely ignored, including in the back room of the local Commercial Hotel. The 1974 tape is also of interest to hear Boyle’s actual voice. In one book he notes the family had a quiet, measured way of speaking, and his own voice was like that. In a sense a voice from 1930s rural Ontario is speaking to us today.

[6] Early Ontario foodways, while a separate topic, was heavily influenced by both British and American practices, the latter coming in initially via the heavy United Empire Loyalist influx in the wake of the American Revolution.

[7] The grandfather of Boyle’s accounts was his maternal grandfather.

[8] Of course, others were doing similar in the United States and Britain. M.F.K. Fisher, James Beard, Elizabeth David, Julia Child, the list goes on.

[9] See last pages of Memories of a Catholic Boyhood.

[10] Boyle writes she noticed early his interest in town girls, of which she was understanding.

[11] See again concluding portions of Memories of a Catholic Boyhood.

[12] Boyle had one sibling, sister Rita, who is largely omitted from the accounts this writer reviewed.

[13] When Boyle entered the working world, the family had stopped farming and opened a general store whose early operation he describes in typically evocative language. The store was not doing well as Depression deepened, which meant no money was available for further studies at St. Jerome. Despite the family’s struggles, Boyle portrays them always with warm language.