Home and Happenstance: How Chance Encounters in the Archive Can Become Sources of Invention

Katie L. Irwin, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

In Working in the Archives: Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition, editors Alexis E. Ramsey, Wendy B. Sharer, Barbara L’Eplattenier, and Lisa S. Mastrangelo interject among the chapters that offer specific archival research strategies stories of “serendipity in the archives.” In these short narratives, scholars reflect on their unexpected archival moments and how “the role of chance” can shape one’s research.[1] Following their example, this post shares my own serendipitous journey of stumbling onto my dissertation topic – and my family – in an archive.

In the Spring 2012 semester, I was taking an Art History graduate seminar and was researching illustrations of farm women that appeared on the cover of The Farmer’s Wife magazine during the early 1930s. Thanks to my university’s library, which made available the full run of the magazine through its Illinois Digital Newspaper Collection, I had an enormous corpus to sort through. I was drawn to the 1930s in particular because the cover art didn’t match, or even slightly mimic, the photographic evidence that visually defined what American life was like for millions of people during the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl.

To understand this discrepancy, I needed to develop a sense of how women had been photographed during this time. I thought of Dorothea Lange’s iconic “Migrant Mother” photograph of migrant farmer Florence Thompson and her three children from their time at a California pea picker’s camp in 1936. Knowing that Thompson worked for the Farm Security Administration, I headed to the Library of Congress’s digital collection of FSA/Office of War Information files. I was curious to see if any photos from my hometown were included, so I narrowed my search and navigated to the Charles County catalogue within the Maryland record. While reading through the names of image files, I saw a name that I knew well: Hardesty, which is my grandmother’s maiden name. Sure enough, my next click opened a photo that made me gasp because the woman pictured looked just like my mother:

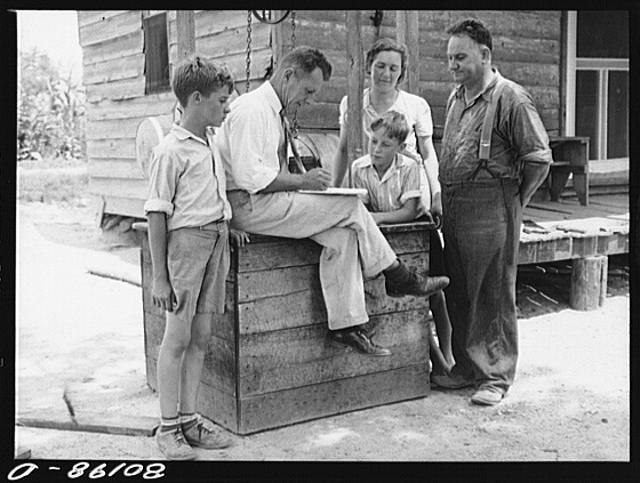

John Collier, photographer. County supervisor talking over home plan with the Hardesty family resting on removed well top. Charles County, Maryland. July, 1941. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/fsa2000051215/PP/. (Accessed August 22, 2016.)

The woman in this photograph is Esther Hardesty, my great-grandmother. Her husband, John, is beside her, and two of their four children join them at their removed well top while a county supervisor explains the new water system for their tobacco farm. Once the initial shock had settled, I started poring over the other 27 photos contained in the “Hardesty Well Project” collection. Their captions revealed that FSA photographer John Collier visited the Hardesty farm in July 1941 to document a new well installation; as he photographed this project, Collier also took a few photographs of my then-eight year old grandmother, Joyce, and her three young brothers. I had only seen one of these photographs before, and I didn’t know the others existed, let alone were available through the Library of Congress. Yet the photograph that I could not turn away from was one that pictured my great-grandmother sitting on her porch with her husband, a health officer, the supervisor of home economics, and a county supervisor surrounding her from all sides.

John Collier, photographer. Health officer, county supervisor and supervisor of home economics discuss home plan with the Hardesty family. Charles County, Maryland. July, 1941. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/fsa2000051219/PP/. (Accessed August 22, 2016.)

At first, it was the symmetry that grabbed me – how the four figures visually echoed one another in both posture and gaze as they turned to the sitting Hardesty. Their framing appeared almost too perfect, which Nan Johnson noted when she mentioned that the photo looked like a tableau during my talk at the 2015 Feminisms and Rhetorics conference. As I lingered with the photo, its composition raised questions specific to the scene: What was my great-grandmother thinking as these people surrounded her? How did she view the agents’ arrival at the family farm and their instruction about water management? Did she have a conversation with them or perhaps question what they advised, or did she accept the knowledge they brought into her world?

My training in visual communication led me to other interpretations. When I teach Visual Politics, an upper-level Communication course that explores the role of the image in shaping public life, my students and I spend the semester reading photographs and other modes of visuality (like public memorials and embodied performances). We situate those visuals in their unique historical, social, political, and ideological contexts to understand their effects, both in the short-term and across time and space. Just as I challenge my students to interpret in multiple ways the subjects of our consideration, my critical sensibilities invited me to read Collier’s image with the same spirit. On the one hand, it looked like everyone was turning to Hardesty for her acceptance or approval. Read this way, the photo communicates the notion that she was, at least in this instance, the decision-maker; she had power. Yet I also saw the opposite: everyone was telling her what to do. Read this way, it seemed like Hardesty was denied the opportunity to make judgments about issues significant to her and her family’s wellbeing.

Of course, rural women’s lives and labor are never as black-and-white as these photographs. As I recently learned, the agents were turning to my great-grandmother because she could read the information, whereas her husband could not.[2] Her literacy, I’ve realized, signified a claim to power within the complicated matrix of gender in rural culture. Her labors of literacy included keeping the family’s records, managing account books, and submitting recipes to local papers for prize money to supplement the family income. In 1987, Hardesty spoke with John Wearmouth as part of the Southern Maryland Studies Center’s Oral History Collection project. During their conversation, Wearmouth was noticeably fascinated at my great-grandmother’s account books. “Lots of people did these things,” he said about the innovative practices that earned extra money. “The difference is you kept track of it.” Hardesty, who had earlier noted that she always enjoyed math in school, replied: “I just made up my mind I was going to do it.”[3]

I didn’t know it then, but my research trajectory changed that day in 2012 when I happened upon Collier’s photos of my family. I read histories of rural life and rural change. I became fascinated with President Theodore Roosevelt’s Country Life Commission and its task of visiting rural people and learning about their problems so that it could recommend how to improve rural life. I found inspiration in Charlotte Perkins Gilman when, in a January 1909 Good Housekeeping article, she questioned of Roosevelt’s all-male assemblage: “Why are there no women on this commission?”[4] I came to see my great-grandparents’ well demonstration project as an echo of the Smith-Lever Act and earlier agricultural extension and home demonstration programs.

I’m now writing my Ph.D. dissertation about U.S. rural women from the 1920s and how their words and practices sustained, challenged, complicated, and redefined popular perceptions of rural womanhood and rural life during an era of change. I’m analyzing a broad range of materials including farm women’s letters, magazine articles, photographs, advertisements, conference proceedings, speeches and other public statements, home demonstration reports, and rural women’s club materials. My goal is to understand how these materials constituted various forms of agency within rural women’s lived experiences. Now, I see that Collier’s photo of my great-grandmother sitting on her farm porch with the agents around her organizes the research questions I’m asking in my project: Whose knowledges, experiences, and worldviews matter when rural culture is viewed as requiring assistance? How did home and field technologies influence how rural women talked about power and choice in their everyday experiences? In what ways did women’s interactions with authorities shape women’s possibilities for public expression? What types of appeals did white and African American women make as they negotiated raced, classed, and gendered perceptions of rural womanhood?

While visiting my family in Maryland this July, I had the opportunity to sit down with my grandmother to talk about her memories from Collier’s visit, the well project, and her life on the farm more generally.

Katie Irwin, photographer. Joyce Cooksey, daughter of Esther Hardesty, discusses Collier’s visit to the Hardesty farm. July 26, 2016. La Plata, Maryland.

As we pored through her mother’s materials that she has collected and preserved over the years, I realized the wonderful irony that has settled over my research. My archival trips have taken me to the Iowa Women’s Archives, the Minnesota Historical Society, and soon, to North Carolina State University’s Special Collections. I’m also incorporating primary sources from the University of Illinois Archives, the University of Iowa Special Collections, and Cornell University’s Rare and Manuscript Collections.[5] Yet despite all of these travels and amazing resources, I never would have imagined that the archive I would come to find most enriching is the one in my grandmother’s house.

Katie L. Irwin is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Communication at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she is the Nina Baym Dissertation Completion Fellow for 2016-17. She serves on the Board of Directors for the Rhetoric Society of America. You can reach her at

kl******@il******.edu

, and you can find her on Twitter at @katieirwin.

[1] See Lori Ostergaard, “Open to the Possibilities: Seven Tales of Serendipity in the Archives,” in Working in the Archives: Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition, ed. Alexis E. Ramsey, Wendy B. Sharer, Barbara L’Eplattenier, and Lisa S. Mastrangelo (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2010), 40-41.

[2] Joyce Cooksey, interview with the author, July 26, 2016.

[3] Esther L. Hardesty, interview by John Wearmouth, February 18, 1987, La Plata, Maryland. Courtesy, Southern Maryland Studies Center, College of Southern Maryland, SMSC Oral History Collection.

[4] Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “That Rural Home Inquiry,” Good Housekeeping, January 1909, 120.

[5] A special thank you to Chris Skurka for helping with the Cornell materials.

I love this story and research. It fits in nicely as a model that we could use in our course at Utah State University, English 3630, The Farm in Literature and Culture. Thank you!