“Dear Miss Cushman”:

The Dreams of Eva McCoy, 1874

Sara Lampert, University of South Dakota

As an early republic historian working on the gender history of commercial entertainment, I am always on the lookout for Carrie Meebers, or women and girls who can open up the longstanding trope of the country girl seduced by the city. Carrie Meeber is the heroine of Theodore Dreiser’s turn-of-the-century novel Sister Carrie. This is a quintessentially urban tale: Carrie is awakened to the seductions and possibilities of mass culture and urban life by her explorations of the city. Her rural girlhood and the dreams that brought her from Waukesha to Chicago are dispensed with in the first page as the rural landscape of her Wisconsin childhood rushes by on her train bound for Chicago. These gestures deploy familiar tropes, rural girlhood as ennui. Carrie releases a faint sigh for “the flour mill where her father worked by the day” and the “familiar green environs of the village,” but as then train picks up speed, “the threads which bound her so lightly to her girlhood and home were irretrievably broken.”[1]

Dreiser does not give us a chance to spend more time with Carrie in Waukesha, to read her letters with sister Minnie in Chicago, survey the sheet music on her parlor piano or open the chest in which Carrie might have kept press clippings and women’s periodicals and catalogs. How might her rural girlhood have shaped her expectations about the world she would exit into at other end of the train line?

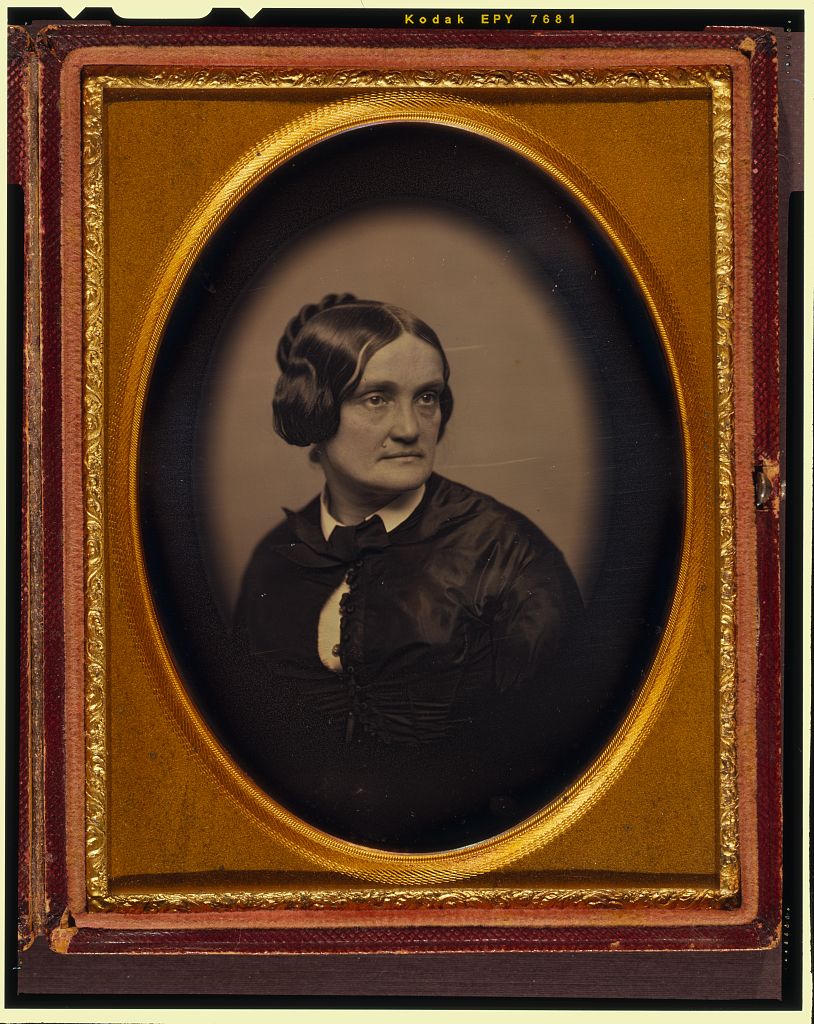

Charlotte Cushman. Half plate daguerreotype, ca. 1855. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division LC-USZC4-13410.

In Washington D.C. while researching 19th century American actress Charlotte Cushman, I briefly stumbled into the world of Eva McCoy, a girl from rural Illinois who penned a piece of fan mail to her idol in 1874.[2] The letter survives today taped into a red bound volume in the Charlotte Cushman Papers in the Library of Congress. It is likely that the letter was received and read by Cushman’s life partner Emma Stebbins, and later saved by Stebbins, who took on the weighty task of managing Cushman’s legacy after the actress’ death from breast cancer in February 1876. The letter was preserved and later mounted, along with miscellaneous fan mail, much of it from the 1870s and much of it from other women.

In 1874, when McCoy wrote to Cushman, she was living in Thomson, Illinois, a town on the Mississippi River that by 1880 counted a population of only 390 people. McCoy painted a portrait of financial depravation matched by frustrated ambition. At only twenty-three, she was “‘alone in the world’ having my own resources to depend upon for existence.” Like Cushman’s other correspondents, McCoy balanced appeals to necessity with testimonial to her passion for the stage. She explained, “Since I was a very little girl, I have been desirous of becoming an actress; however, I have never had an opportunity of becoming educated for the Stage.”

Here was the reason for her letter. McCoy wanted instruction, but not from the “gentlemen…managers of the Stage.” Though she readily admitted to an “adventurous and courageous nature,” McCoy feared for her virtue: “strange men may be ‘hideous monsters’.” Instead, she fantasized about coming to live and study with Cushman. She promised, “I will love you as a darling sister, or a mother,” “be obedient,” and “become your own.” Whether as a “servant or companion,” McCoy only hoped to “sustain a relation” to Cushman in “whatever capacity it may please you to place me.” She enclosed a photo.

McCoy’s desperate and passionate appeal was not unusual. Other women and girls who wrote to Cushman struggled to frame professional desires and naked worship of their celebrity object in a more socially acceptable narrative of economic necessity, often describing poverty and family need. Like McCoy they collapsed the fantasy of student in the role of devoted servant to their desired object. As Cushman’s biographer Lisa Merrill has demonstrated, throughout Cushman’s life and career, women were drawn to her, whether because of her performances and the inspiration and lessons that they read from her life and career. Cushman’s determination to be breadwinner for her widowed mother and siblings was an established feature of her biography, which also shaped her reputation as a true woman who was both virtuous and charitable. Merrill points out, however, that some women may well have read the “code” of female erotic desire in Cushman’s relationship with Stebbins or her performances of male roles like Romeo.[3]

Correspondents like McCoy dreamed that Cushman would be moved to aid them. McCoy’s letter in particular reminds us that Cushman’s publics included girls and women who had never seen her perform, would never see her perform, but for whom Cushman’s celebrity held significance and inspiration.

But was Eva McCoy exactly as she appeared? Was her careful appeal actually a careful manipulation of sympathy or did it conceal an even sadder truth?

McCoy had lived in rural Illinois her entire life. Her parents John Vallette and Clarinda (Walker) Vallette came to DuPage, Illinois from the Northeast in 1839 during a period of rampant land speculation in the Big Woods.[4] Their daughter Evaline was born a decade later, the eldest of three. In 1860, her father was earning a living as a “homeopathic physician” with only $100 to his name owning real estate worth $1000.[5] After serving briefly as a hospital steward with an Illinois regiment toward the end of the war, he seized the opportunity of new settlement made possible by postwar railroad construction.[6]

In 1866, he went into partnership in the dry goods business with the widow of a local physician and druggist. Their new home would be a small village laid out by the Western Union Railroad in a valley on the banks of the Mississippi River at the western edge of the state.[7] The new partnership and move to Thomson was a boon to the family fortunes. In 1870, Vallette boasted a personal estate worth $5000 and $3000 in real estate. The former “homeopathic physician” now titled himself “medical doctor” on the federal census. His son clerked in the family business and his daughter was married to a young lawyer, Daniel McCoy.[8]

The couple had married in November 15, 1865. He was twenty-two, she eighteen.[9] By 1870, Daniel possessed a respectable personal estate of $1000. After 1870, he disappears as does Eva McCoy, though we know that in 1874 she was writing Charlotte Cushman hoping for…something.

Where was Daniel McCoy in 1874? Born in Ohio, he was one of the many Daniel McCoys who served in Illinois regiments in the Civil War. Was he the Daniel McCoy who had served with the 45th Illinois Infantry and died March 18, 1873, laid to rest in Peoria, Illinois?[10] Perhaps he had been mustered out for the very injury that would cause his death eight years later. Perhaps Eva’s loneliness was not that of a widow but of a deserted wife. Most likely he died and she hauled stakes. Though its unlikely she received a reply from Cushman, perhaps writing the letter gave her the courage to leave the comfortable estate her father had built for himself in Thomson and try her luck in Chicago, travelling by the Western Union Railroad, a little bit older and perhaps with a bit more saavy, though less ultimate success, than Sister Carrie Meeber.

[1] Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie (Penguin Books, 1994), 3.

[2] Eva McCoy to Charlotte Cushman, November 15, 1874, Charlotte Cushman Papers, Library of Congress.

[3] Lisa Merrill, When Romeo was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and her Circle of Female Spectators (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999).

[4] The History of Carroll County, Illinois (Chicago: H. F. Kett & Co., 1878), 425.

[5] 1860 U.S. census, Wheaton, Du Page, Illinois, page no. 195, dwelling 1451, family 1494, John O. Vallette, digital image, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com).

[6] Rufus Blanchard, History of Du Page County, Illinois (Chicago: O.L. Baskin & Co. Historical Publishers, 1882), 121.

[7] History of Carroll County, 365.

[8] 1870 U.S. census, York Township, Carroll, Illinois, page no. 36, dwelling 278, family 278, John O. Vallette, digital image, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com); 1870 U.S. census, York Township, Carroll, Illinois, page no. 34, dwelling 257, family 257, Daniel McCoy, digital image, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com).

[9] Illinois State Marriage Records, Illinois Marriage Index 1860-1920 [database online], Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com) based on Illinois State Marriage Records.

[10] Daniel McCoy, Pvt. Co. C, Regt. 47, Illinois Infantry, date of death March 18, 1873, digital image, Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, 1879-1903 [database online], Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com) based on Card Records of Headstones Provided for Deceased Union Civil War Veterans, ca. 1879-ca. 1903.