The Catholic Worker Farm in Tivoli, a View into the Past

Sally Dwyer-McNulty, Marist College

The Catholic Worker Movement Collection is held at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Beyond Marquette’s vast repository, however, there are some Catholic Worker artifacts that could never be stored in a traditional archive. And, as luck would have it, the “document” I was most eager to examine, was not far from my home in upstate New York. It was the farm that Dorothy Day purchased in Tivoli, New York in 1964. Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin launched the Catholic Worker Movement in response to the Great Depression in 1933. They used The Catholic Worker newspaper to communicate the value of voluntary poverty and mutual aid, and they relied on their Houses of Hospitality, and various farms to live out their values with other likeminded individuals and those in need. Tivoli, was the location of one such farm.[1]

There are few detailed accounts of the Tivoli Farm, but what has been recorded, is not very favorable. Oral histories and reminiscences note the farm’s beauty, but most historians conclude that it was a chaotic residence, which was often overwhelmed by non-contributing visitors.[2] Ultimately the farm community could not be sustained. Although the Farm has been closed for almost 40 years, I wondered what I might learn about its attraction and demise by simply walking through the property and observing the land and buildings. The present owners, kindly agreed to let me visit, and I took an afternoon to explore the grounds and think about what brought Day to Tivoli and the significance of this location.

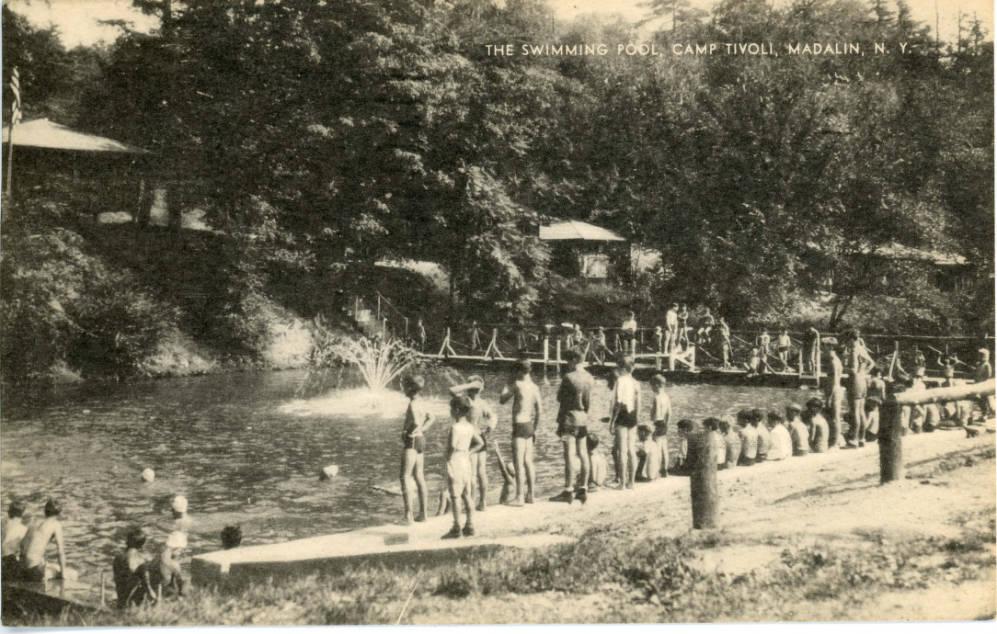

According to Day’s granddaughter, Kate Hennessy, not long after learning of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Day saw an advertisement for an 87 acre farm “on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River,” in Tivoli, NY, just 100 miles north of New York City. The property was “suitable for a religious group,” and included a thirty-two room boarding facility, a 19th century mansion, and a carriage house. The mansion also had a swimming pool.[3] Upon visiting the grounds, Day saw a plaque with the words “Beata Maria” or Blessed Maria prominently displayed on the mansion. All the signs were there for Day: ample space for a new farm and plenty of rooms for workers and guests, “a stream of living water”, and a reference to Mary, the mother of Jesus.[4] Day decided to use the proceeds from the sale of another property on Staten Island to put a down payment on the Tivoli Farm.

Bob Fitch, Catholic Worker Farm, Tivoli, New York 1968. Dorothy Day and John Filliger. Bob Fitch photography archive, © Stanford University Libraries

Scholars tend to associate the establishment of Catholic Worker farms with Peter Maurin, Day’s “cradle-Catholic” mentor and partner in establishing the Houses of Hospitality and newspaper. Maurin was born to a farming family in Langeudoc, France in 1877. He spent time in a religious community, as a Christian Brother, but left the order in search of a different model of Catholic service. Influenced by decentralist agrarians such as Hilaire Belloc and G.K. Chesterton, along with monks of the Benedictine Order, Maurin imagined creating an integrated community of “cult, culture, and cultivation” where scholars and workers could distance themselves from the capitalist system and come together to learn from each other and build a community with a foundation of work and prayer.[5] The Catholic Worker established farms on Staten Island, New York; in Easton, Pennsylvania; and in Newburgh, New York. Maurin appeared to be the strongest advocate of combining farm communes with their New York City efforts.[6] Nevertheless, by the time Day bought the Tivoli property in 1964, Maurin had been dead for 14 years. Tivoli was her first independent farming venture.

It’s unclear if Day knew that Tivoli had, itself, been founded as a kind of utopian inspired community at the end of the 18th century, but perhaps the street that intersected her future property, “Friendship Street” gave her some indication of its intentional origins.[7] Back in 1795, Frenchman and successful New York City merchant, Peter DeLabigarre, purchased 248 acres along the banks of the Hudson River in Upper Red Hook and married the daughter of a prominent Hudson Valley family, Margaret Beekman.[8] DeLabigarre chose the name “Tivoli” for his ideal community after the picturesque town of Tivoli in central Italy.[9] According to a copper engraving of his community, commissioned by DeLabigarre, he imagined “a gridiron of house lots and sixty foot streets” as well as “a market and docks along the river and, on higher land a community park or ‘pleasure ground.’”[10] The community, as other street names indicate, would promote “Commerce, Plenty, Peace, Liberty, and Friendship.”[11] By 1807, however, DeLabigarre was bankrupt and his utopian dream ended.[12]

The Tivoli land that would become the Catholic Worker Farm, was established in 1843 as a summer home and country retreat for General John Watts de Peyster and his family. They named the mansion and property Rose Hill. Shortly before de Peyster died, he transferred Rose Hill to the Leake and Watts Children’s Home for $1.00.[13] Over the next forty years, Rose Hill would function as an orphanage. And during World War II, the former dormitory for the young boys would house members of the “land army” or “young city people who volunteered to work in the area’s farms” while the local men were off at war.[14] By the time Day acquired the Rose Hill property it was fairly run down from hard use, but the bones of excellent architecture were still apparent.

Swimming pool, Camp Tivoli, Madalin N.Y. Ward Manor Collection, Historic Red Hook. https://www.hrvh.org/cdm/ref/collection/hrh/id/141

Not unlike Tivoli’s founder DeLabigarre, Day had elaborate plans for the Catholic Worker Farm in Tivoli that include many similar goals, especially liberty, peace, and friendship. As an anarchist and believer in voluntary poverty, Day would not have shared DeLabigarre’s interest in commerce and plenty. The property would function as a farm, but also, a House of Hospitality, Folk School, a place for silent retreats, and peace conferences. The newspaper press would also be housed in Tivoli, and there would be a chapel, library, and plenty of space for sleeping workers and visitors. According to Day, in this last agronomic university, “the entire school will be staffed by our ‘community of need’… The scholars will become workers, and the workers scholars…” just the way Maurin proposed so often in the past.[15] The Catholic Workers, visitors, observers, needy, and ill came to Tivoli, but Day’s last rural community only survived until 1978.

On my visit to the former farm, I wondered what I would be able to sense about the allure of the location and the problems that beset the community at Tivoli. Parking at the end of a backroad that came down to the Hudson River, I was surprised by property’s close proximity to the water. It was indeed a beautiful location, with magnificent views, but not an ideal site for any intensive farming. It was clearly a sharp drop to the Hudson and the land near the water was rocky. Matt, the caretaker, met me by the water and I climbed into his SUV for a drive to the mansion. As we made our way up the dirt road, I noted that like several of the 19th century mansions on the Hudson River, there were thickly wooded areas with narrow trails shooting off in different directions. This environment was perfect for collecting natural specimens or a meditative walk, but again, I wondered about where they would farm.

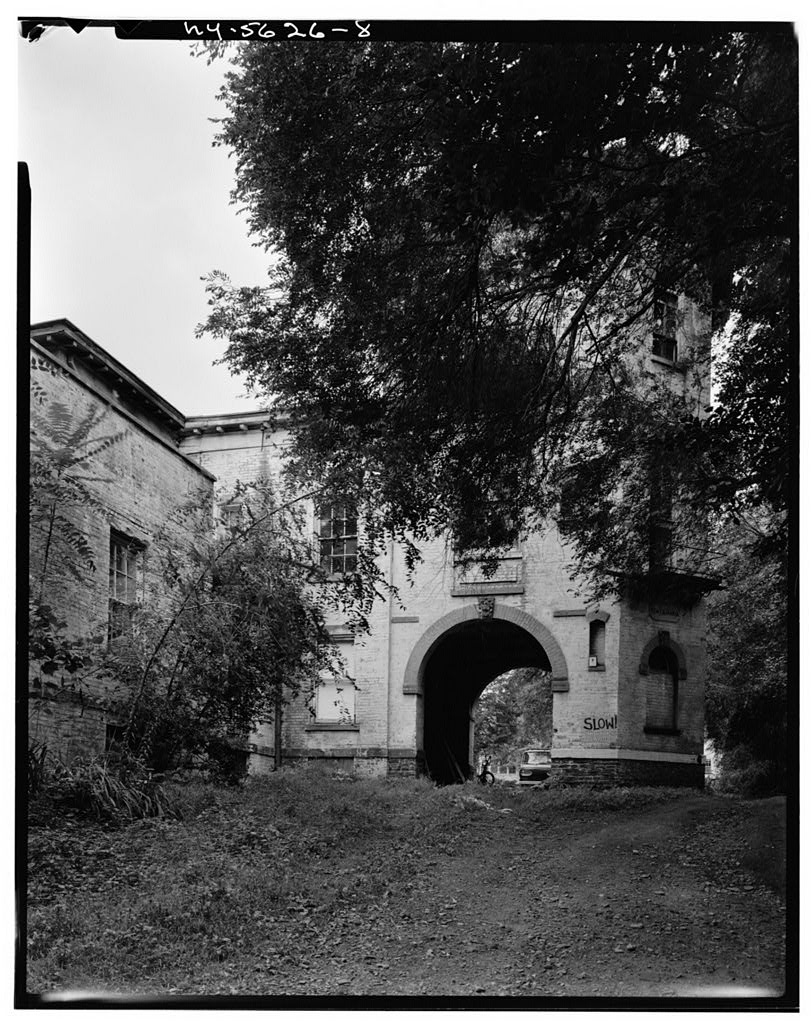

Arriving at the top of the road, I took my first glimpse of the mansion. I could see, immediately, that its Italianate architecture conveyed a Catholic feeling and space — one that would have been comfortable and familiar to Day who so frequently sought out Catholic places. The architecture, just like the chiseled sign Beata Maria, imbued the location with Catholic associations. Inside the mansion, many of the doorways were small arches, like those in Catholic monasteries throughout Italy. While a concern for the poor is a consistent Catholic priority, official Catholic spaces, especially those built in the 19th and early 20th centuries, are not known for their impoverished appearance. Instead, the churches, convents, monasteries, and schools are often identifiable by their architectural impressiveness whether it be stonework, size, tile, or art. I imagine Day appreciated this common Catholic juxtaposition of grandeur and poverty. Day easily reconciled the opposing Catholic interests in a hand-lettered sign prominently painted on a lovely stone wall in the mansion vestibule. “Men’s Pants” with an arrow facing down indicated where visitors in need of clothes could find trousers in the grand estate. Fortunately, the current owners recognized this curious feature of their home’s history, and decided to keep it. The potential majesty of the mansion did not obfuscate the basic requirements of its residents.

SOUTH FRONT OF TOWER WITH ENTRANCEWAY AND ARCH – Rose Hill, Woods Road, Tivoli, Dutchess County, NY. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ny0195.photos.116215p/

The dormitory was another large structure on the site, not splendiferous like the mansion, but nonetheless similar to another kind of Catholic space, the school institutions or the houses of the religious. Catholic orders frequently carried out their charism or special service, and financially sustained their religious families, through the administration of schools and orphanages. The former Leake and Watts Children’s Home, while not Catholic, shared that same dedication to benevolent institutionalization. Again, I thought this building too, would have excited Day, since her own leadership was similar to that of an abbess in an alternative-style monastic order.

Day, in particular, was devoted to the Benedictine tradition, and made her profession as an Oblate of St. Benedict in April 1955 at St. Procopius Abbey in Lisle, Illinois.[16] One of the long time Catholic Workers who knew the Tivoli Farm well, Stanley Vishnewski, noted the importance of the monastic influence on the Catholic Worker. “I am sure that without the influence of the Benedictines,” he explained, “there would be very little in the Catholic Worker Movement – For from the Benedictines we got the ideal of Hospitality – Guest Houses – Farming Communes – Liturgical Prayer. Take these away and there is very little left in the Catholic Worker Program.”[17] Monastic traditions, whether in prayer, silence, or community living deeply attracted Day. She even had monastic neighbors whom she liked to visit, less than 2 miles away. The Carmelite Sisters for the Aged and Infirmed came to Avila-on-the-Hudson in 1947 and welcomed Day into their home when she arrived in the neighborhood. It was easy to see how Day could imagine living out some of the Benedictine traditions in Tivoli.

Despite the comforts of Catholic symbols, spaces, and inspirations, the Farm would need to be productive to sustain an active community. And, it was the farming that I failed to picture. According to local historian Bernard B. Tieger, “only about an acre of land was even cultivated, and farming never became a dominant feature of the Farm.”[18] Rather than a Farm, it seemed like a large and potentially diverse garden with fruit trees occupying some of the open and flat areas of the property. There are many farms in Northern Dutchess County and surrounding counties, but as Tieger observed, the most popular crop in the area was fruit, which accounted for 84% of area farm production by 1936.[19] It didn’t mean that other crops or livestock were not possible, but there was not enough evidence of land under cultivation, grazing areas, or animal shelters to support an active and often crowded anarchistic community.

I went home from this fieldtrip with a better sense of why Tivoli was so attractive to Day, and also at least one reason why it didn’t work out as she had hoped. Maybe as she approached the end of her life, it was the natural cloister and religious spaces that inspired her decision to purchase the Tivoli Farm. Clearly crop yield and farm production did not greatly influence her choice. The land had limited potential for sustaining its often needy residents. After having appreciated my local “archive,” I am eager to view and listen to another set of artifacts at Marquette, and study more texts about Day’s years at the Tivoli Farm.

[1] Audrey H. Cole, “The Catholic Worker Farm: Tivoli, New York 1964-1978,” The Hudson Valley Regional Review, March 1991, 8, no. 1 (March 1991): 25-27.

[2] Ibid., 34-35.

[3] Kate Hennessy, Dorothy Day, The World Will be Saved by Beauty (New York: Scribner, 2017), 229-30.

[4] The reference to “living water” comes from Dorothy Day’s diary entry of 13 December 1963 included in Robert Ellsberg, Ed. The Duty of Delight: The Diaries of Dorothy Day. (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2008), 345.

[5] Anthony Novitsky, “Peter Maurin’s Green Revolution: The Radical Implications of Reactionary Social Catholicism,” The Review of Politics 37:1 (January 1975): 90, 100-1.

[6] Mel Piehl, Breaking Bread: The Catholic Worker and the Origins of Catholic Radicalism in America (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982), 65.

[7] Richard C. Wiles, Tivoli Revisited: A Social History, (1981), 5. Local History Collection, Tivoli Library; Tivoli, NY.

[8] Joan Navins, Tivoli 1872-1972: A Historical Sketch (Rhinebeck, NY: Jator Printing Company, 1972), 12.

[9] According to The Utopian Impulse, an 2009 exhibit at the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University, from the 15th through the 18th there was an notable increase in “expressions of the utopian impulse” or “planning of ideal cities and societies” in Europe and the Americas. The humanistic values of the Renaissance coupled with the possibilities offered by the discovery of the “New World” inspired visionaries to reimagine society. The exhibit creators identified New Haven, Connecticut, the home of Yale University, as an 18th and 19th century community inspired by the desire for “safety, plenty, and freedom.” Likewise, its nine-square plan was a recognition of the priority of a “planned” community.

See http://www.library.yale.edu/exhibitions/ideal/images/utopian_impulse.pdf (accessed October 10, 2017).

[10] Navins, 16.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Bernard B. Tieger, Tivoli: The Making of a Community (Tivoli, NY: Village Books Press, 2012), 87.

[14] Ibid., 137.

[15] Cited in Brigid O’Shea Merriman, Searching for Christ: The Spirituality of Dorothy Day (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1994), 160, from Dorothy Day, “On Pilgrimage” The Catholic Worker (June 1964): 1, 2, & 6.

[16] Merriman, 106. An oblate is a lay person who professes an association with a religious order and maintains certain rules such as participating in the Liturgy of the Hours or saying prayers at designated times of the day.

[17] Stanley Vishnewski to Brother Benet Tvedten, O.S.B., 14 August 1968, Marquette University Archives. Dorothy Day- Catholic Worker Collection, W-12.3, Box 3, cited in Merriman, 107.

[18] Tieger, 138.

[19] Ibid., 121.

One of the photos is mislabeled. The man with Dorothy Day is John Filliger, not Stanley Vishnewski. Both men were with the CW since its early days in the late 1930s and its first farm in Easton PA. John Filliger was the main farmer on all five CW farms including the one at Tivoli. I was born into the CW in 1942 and knew these people all my life.

A number of the Bob Fitch photos housed at Stanford University Libraries misidentify the people depicted. I and others have requested corrections.

Tillman,

Thank you for reading and sending along that correction. I will fix the label and let the Stanford University Library know of the mislabeling. If you’re interested, I would be delighted to learn about your experiences on the farms. My email address is sa*****************@ma****.edu.

Thank you for the excellent piece. I spent the summer of 1967 resident on the TIvoli “farm”. I think your treatments of both D. Day’s ideal vision and the real situation there are well balanced and fair to all parties.