Kymara D. Sneed, Mississippi State University

I’ve always been told that the history you study is a reflection of yourself. How true that statement is. If someone asked me in 2014 what I planned to do with my degree, I would have shrugged my shoulders and uncertainly replied, “I don’t know.” All I knew was two things: that I am a History major and no, for the millionth time, I am not going to teach social studies. In hindsight, my research interests were broad and unfocused as an undergraduate. However, my junior and senior years at Fort Valley State University helped narrow them down. I owe this to my mentor and professor Dr. Dawn Herd-Clark, who introduced me to the intersection of agriculture, black women, and land-grant extension work. It is because of her that I began studying Margaret Toomer and eventually found my way to Sadye Hunter Wier, two of the many black women who used agriculture to build a community in the era of Jim Crow. I saw something of their lives in mine. I saw something of their origins in mine. Thus began my path as a historian.

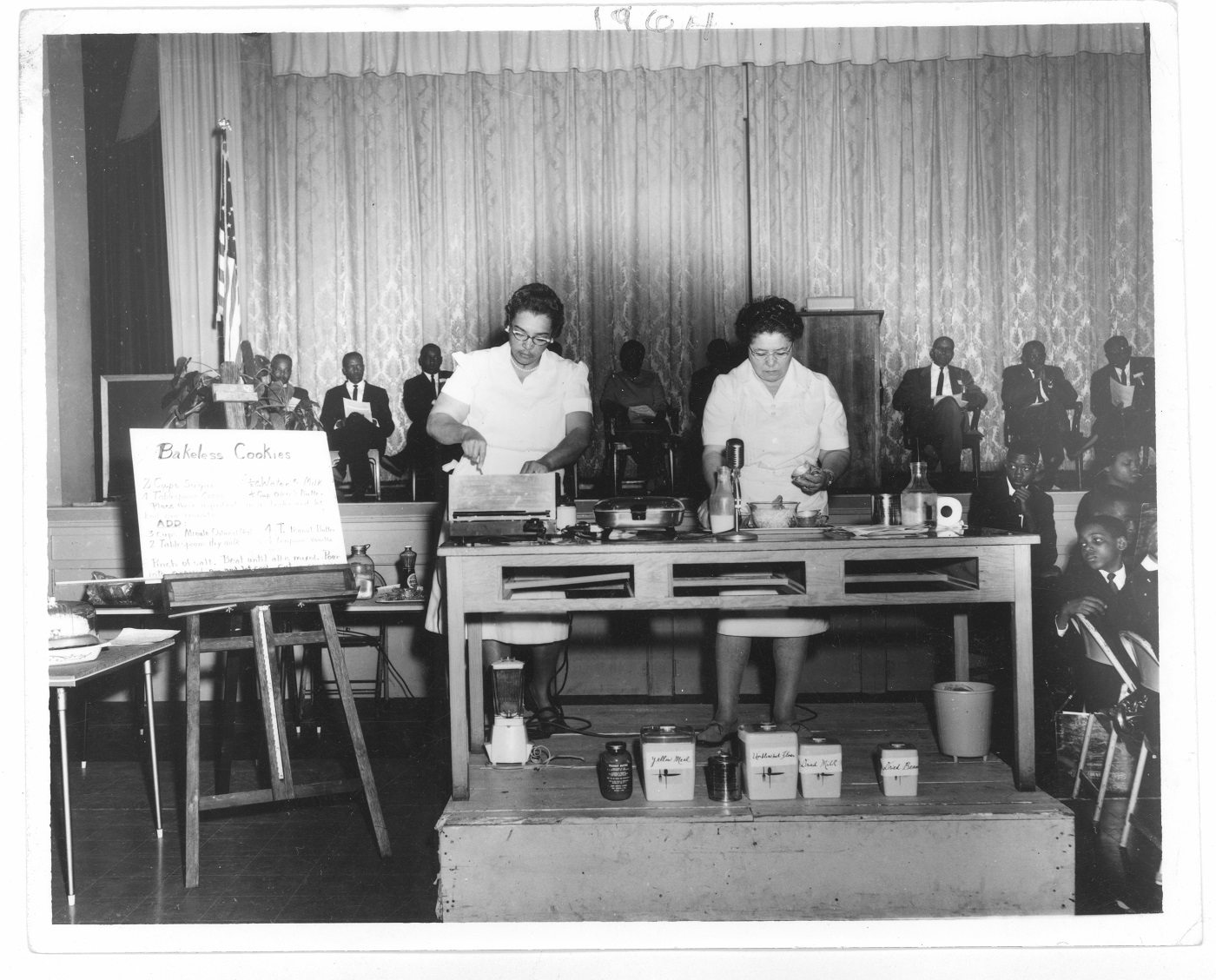

It could have been the similarities in our upbringings, coming from families that endured Jim Crow. I like to think that agriculture runs in my blood, being the descendant of sharecroppers. Looking back, I don’t think it was a coincidence that extension work became my focus. Despite attending Fort Valley State, Georgia’s 1890 land-grand institution dedicated to agricultural and industrial education, Margaret Toomer was my first encounter with agricultural extension work. An organization under the umbrella of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Cooperative Extension Service aided farmers in areas such as home improvement, food preservation, and livestock care. A fellow Georgia native herself, Toomer was a Home Demonstration Agent—a title held by women in the service—who dedicated her tenure to home improvement among the black farmers of middle Georgia. Moreover, she collaborated with Farm Demonstration Agent Otis O’Neal to co-chair then-Fort Valley College’s Ham and Egg Show, a local fair dedicated to agricultural education. The show became so popular that multiple states throughout the South adopted their own versions. O’Neal may have been the face of the show, but my work uncovered how important Toomer was to its genesis, popularity, and longevity. At the time, I was completely unaware that Fort Valley State held this kind of history; despite liking the project immensely, it hadn’t occurred to me that extension work would be my calling as a historian. However, Toomer and I both benefitted from this journey. Her contributions to black extension in middle Georgia gained more recognition and I laid the foundation for what would become my graduate career.

My studies took me to Mississippi State University, another land-grant institution. Margaret Toomer may have been the end goal, but my seminar classes led me to exploring the life of yet another black home demonstration agent: Sadye Wier. Mississippi born and raised, Wier came from a family of educators and used that background as the foundation for her work with local families and clubs. Wier’s social standing proved advantageous in her career. Her husband Robert Wier was a local businessman and cultivated close relationships with Starkville’s elite. Even after retiring from Cooperative Extension Service, Sadye Wier remained a pillar of the black community by championing local causes and working with nearby grassroots organizations. To accomplish this in the era of Jim Crow is a feat in and of itself and yet… she did it. More importantly, though, it woke within me a great desire to enact change the same way by helping farmers acquire the resources necessary to improve their homesteads, especially in the era of corporate farming.

Is it plausible to say that because of these two women, I can see the intricacies of race and gender in agriculture? Certainly. Agricultural history helped me contemplate broader themes within Southern and American history. I have uncovered historical precedents I didn’t know existed. But most importantly, my researched has allowed me to draw parallels with black farmers then and now, especially with the political climate surrounding their lack of funding. The social implications of agricultural extension is complex and relatable; I have, through family members, come across many stories of growing up the children of sharecroppers or enduring the constant dismissal of the plight of black farmers in today’s society. Though their voices are growing louder, it is my sincerest hope that my skills as a historian will not only contribute to cooperative extension’s small but impressive historiography, but will enact change in the fields of agricultural and rural development. I can only stand on the shoulders of Toomer and Wier and marvel at the view.