Contextualizing Women’s Movements in the Appalachian South

Jessica Wilkerson, University of Mississippi

My research started with watching a movie. The women characters of the award-winning documentary film “Harlan County: USA” (1976) made indelible impressions on me. Mothers, daughters, and sisters of coal miners in Harlan County, Kentucky, organized in support of men who went on strike to pressure the Eastover Mining Company to recognize their vote for the United Mine Workers of America in 1973. The women formed what they called the Brookside Women’s Club. The director Barbara Kopple celebrated the women’s courage and offered an intimate look at their lives and struggles, as well as their vision for a better life. In deeply moving scenes, the women describe their motivations, join picket lines, participate in civil disobedience, lead joyful protests, speak out against authorities, argue amongst themselves, and come to peaceful resolutions about how to forge ahead. Some of them are loud and brash, and others are soft-spoken and thoughtful. The film takes the audience on a dramatic journey in which a community fights villainous capitalists and comes out on top, with the miners winning union recognition and a contract.

The film launched my study of women’s activism in the Appalachian South. That region is still often considered by many to be isolated and backwards, a political and cultural island. Yet, I was struck by how the people of Harlan County adopted protest-styles of the civil rights movement and interacted with filmmakers and other union supporters from around the country. The title gestured to the broader significance of the story, of course, placing Harlan County in the “USA.” Still, a film by necessity is limited in scope, and a good film leaves one wondering about the rest of the story. What happened when the cameras left? What could I learn about the women, about their lives before the strike and before the film made them into icons? What would it mean to contextualize their lives, placing them in U.S. political and social history? For some it may be seductive to see rural and Appalachian women as part of distinctive cultures and places, but as a historian of U.S. women’s and gender history, I find it much more productive to place the politics of these women within broader U.S. history. Their history helps us to understand big trends in 20th century American history, like the relationship between class and gender, as well as the promises and limitations of the 1970s labor and women’s movements.

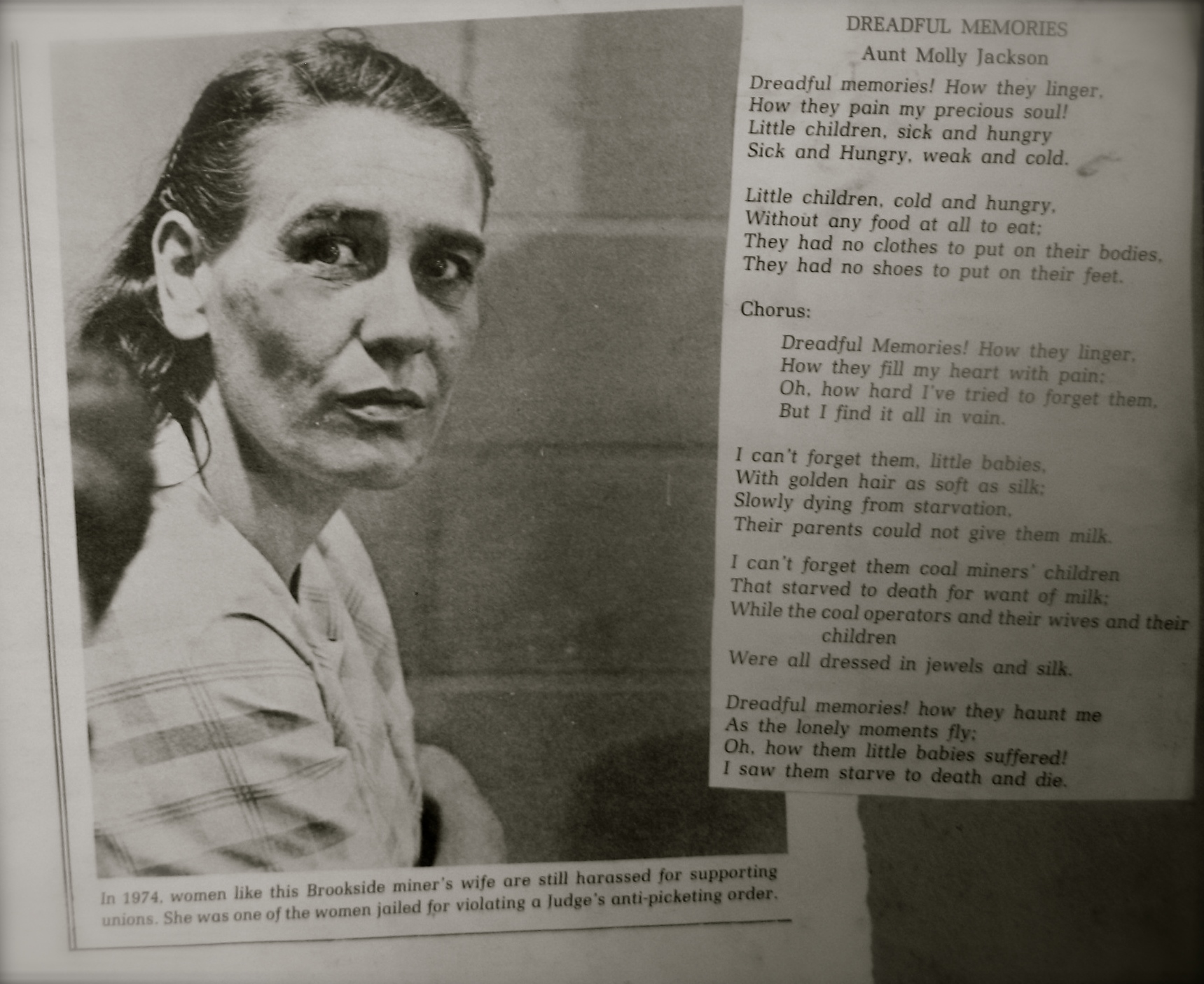

A page from Sudie Crusenberry’s scrapbook, where she documented the strike and the women’s involvement in it. Here she pasted a photograph taken by activist Si Kahn alongside the lyrics of a song by Aunt Molly Jackson, who was involved in Harlan County union struggles in the 1920s. Image courtesy of the Appalachian Archives, Southeast Kentucky Community and Technical College College, Harlan County, Kentucky.

I found that women’s participation in the Brookside strike was one link in the chain of a diverse Appalachian Movement, mobilized by women and men in Appalachia, white and Black, and insiders and outsiders. The movement built on the federal War on Poverty; it carried on the traditions of the 1930s labor struggles in the mining communities, in which women were the folk singers and carriers of collective memory; and it intersected with working-class struggles and the women’s movements of the 1970s and continued into the next decade. People of the Mountain South exposed environmental, labor, gender, and class injustice and organized at the grassroots and within organizations to effect change. Women in Appalachian Kentucky were animated by many of the same concerns that rippled across communities, especially rural and working-class communities, in the United States in the 1970s.

Most surprising to me was how some of the women explained their activism in the context of the women’s movements of the period. Like working-class and poor women elsewhere they showed how class and gender intersected in their daily, lived experiences, and they spotlighted their roles as caregivers. The women’s movement is most often remembered (and, in the present, the focus is still often on) the composition of the labor market, but working-class women from Appalachia, along with textile workers, farmworkers, domestic workers, and others, showed how capitalist markets created structural inequality that hurt working-class communities and had specific implications for the working-class caregivers in those communities. Journalists and reporters at the time used the trope of the woman who “stands by her man” to describe the strike and too often ignored the stakes of the union battle in the lives of working-class caregivers. The Brookside women were not only fighting for the rights of male workers, but, in the words of Brookside Women’s Club leader Sudie Crusenberry, “in support of my own children, too, that I’m raising up.” Their fight became one for the broader community, for their families, and for themselves.

Jessica Wilkerson is assistant professor of history and southern studies at the University of Mississippi. In the 2016-2017 academic year she will be a fellow at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, where she will be completing her book Where Movements Meet: From the War on Poverty to Grassroots Feminism in the Appalachian South (University of Illinois Press, forthcoming). She recently published an article about women’s involvement in the Brookside strike in Gender & History (April 2016).

It’s going to be finish of mine day, but before finish I am reading this wonderful paragraph to increase my knowledge.