Farm Women, Dairymaids, and the Welfare State: Story of an International Collaboration

Grey Osterud

In 2019, a short, English-language book that collects and condenses Lena Sommestad’s research on rural women’ history in Sweden will be published by Routledge/Taylor & Francis. Agrarian Women, the Gender of Dairy Work, and the Two-Breadwinner Model in the Swedish Welfare State is the fruit of my collaboration with Sommestad, a Swedish economic historian, feminist, and Social Democratic activist. In 1992, Sommestad published a path-breaking book on the employment of women as skilled workers and managers in centralized dairies, which analyzes the changes in the labor process, vocational education system, and wider culture that led to the masculinization of the occupation during the interwar period. While her book became an academic bestseller in Scandinavia, in part because of its exemplary combination of documentary records and oral histories, Sommestad turned her attention to the provisions of Sweden’s welfare state that enabled married women to combine breadwinning with childrearing. She discovered that the national association of rural women joined with feminists in the Social Democratic Party to establish these principles during the 1930s. So, at the same time that she held a series of advisory and then elective and appointive positions in the party and the government, Sommestad did research on the origins of the gender-equal welfare state, to which rural women’s activism and agrarian ideas about women’s gainful labor were central.

I first met Lena at the Berkshire Conference on Women’s History in 1991, when RWSA founder Joan Jensen introduced us and suggested that I drive Lena to the airport afterwards. That plan morphed into a week-long tour of farms and rural history museums in Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. Over the next few years Sommestad came to the US to do comparative research in California and Massachusetts when I was living nearby, so we stayed in touch. But for 20 years her Swedish-language book sat on my shelf—unread. When I was at a conference in Scotland and she was at her family’s summer cottage on Sweden’s west coast, she suggested I take a short plane ride and come to visit her. She took me on a tour of rural Norway and Sweden, which began at my great-grandfather’s natal farmstead in central Norway and ended at her home near Sweden’s east coast. I saw two very different rural societies existing side by side: upland areas with scattered family farms engaged mainly in small-scale dairying, where women are not only active farmers but also inherit and own farmland, and plains areas that look depopulated but have huge grain fields rented or owned by agribusiness companies and operated by machinery contractors, where women seldom engage in farming but hold off-farm jobs.

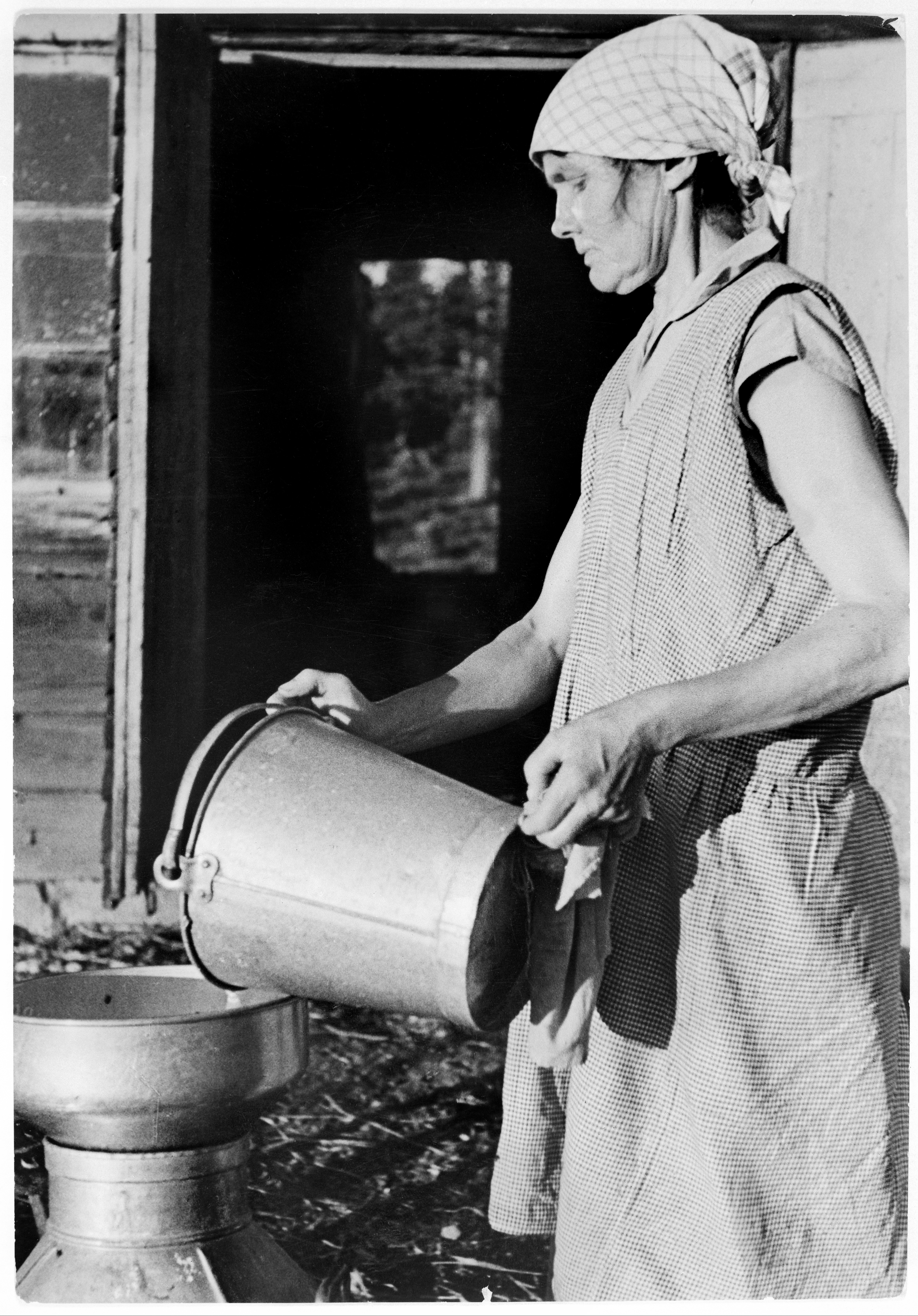

Gunnar Lundh, “Woman straining milk on a farm in the coastal area of Stockholm County in 1935.” In the collection of the Nordiska Museet, Stockholm, Sweden, NMA 0000173.

The rest, as they say, is history. I set out to understand the historical trajectories that have led to such disparate situations in this small region of northern Europe, which shares a social democratic political orientation. After reading everything I could find in English and making several short visits to Scandinavia, including attending a Nordic Women’s History conference where some presentations and most informal conversations were conducted in languages I did not understand, I decided to learn Swedish. Lena Sommestad’s book was the first I translated. The task was easier than I expected because I was already familiar with farming and dairy processing from my own research, and I had visited Scandinavian outdoor history museums that represent the rural past. I am still perplexed by the vernacular speech used in interviews and oral histories, but after four weeks of immersive instruction in Swedish and countless hours of independent study I can read academic and local histories as well as early twentieth-century novels about rural life. I read very slowly, paying close attention to the authors’ unstated assumptions and subtle arguments about gender relations and ideologies, past and present.

About five years ago, once I realized the scope and significance of Sommestad’s body of work, I decided that it should be published in English. We soon discovered that publishers were not interested in a monograph on one small country, but that several have recently begun publishing shorter books—Routledge calls them “Focus” books, Palgrave calls them “Pivots”—that engage important substantive and theoretical questions. I used my professional skills as a book development editor to condense Sommestad’s work into a 50,000 word text that presents her main arguments in relation to key questions in women’s history, particularly the changing valuations of work and the gender division of labor during the process of industrialization and urbanization and the formation of the welfare state—all within a comparative perspective.

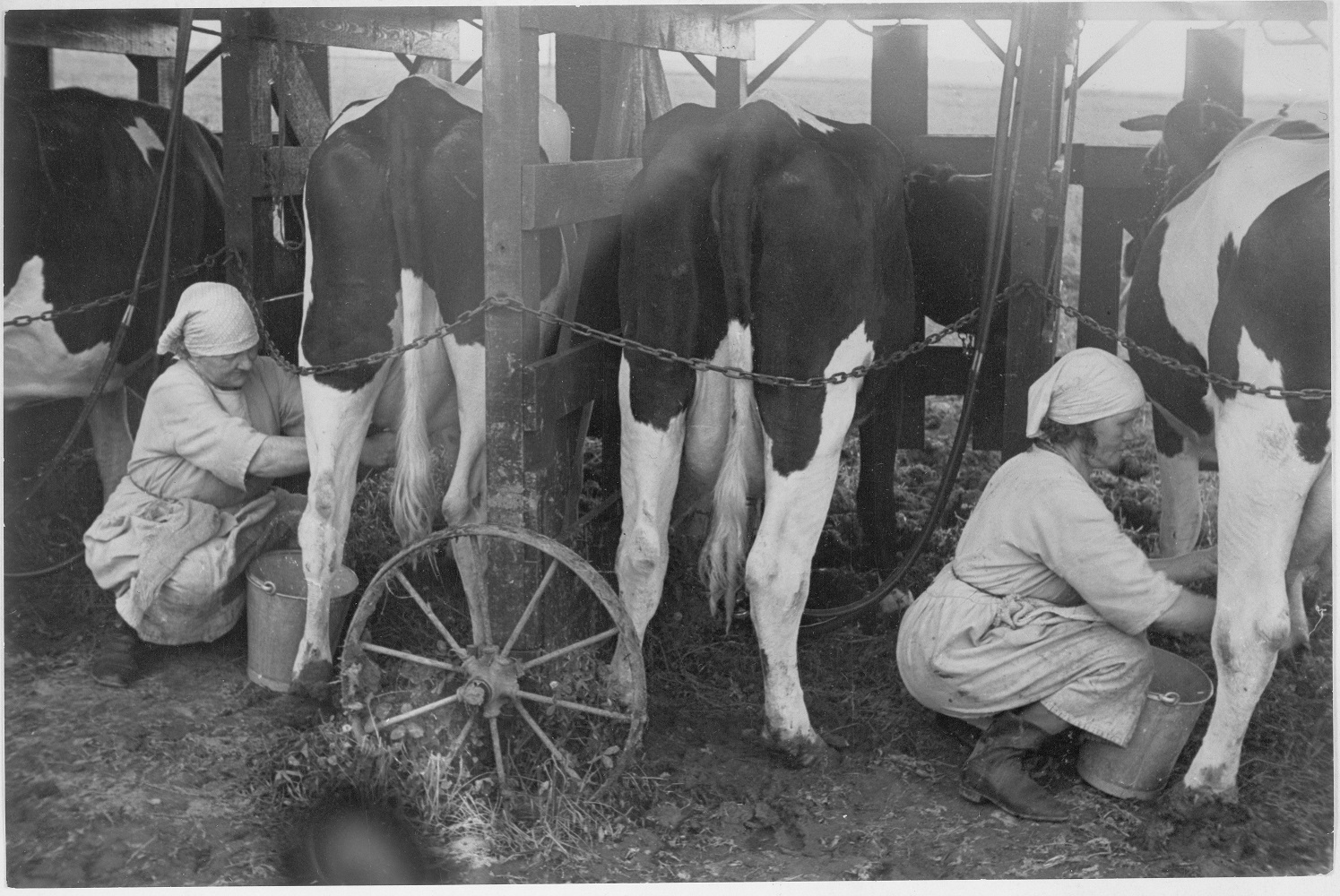

Gunnar Lundh,“Women milking cows by hand on a farm in Skåne in south-eastern Sweden in 1946.” and are in the collection of the Nordiska Museet, Stockholm, Sweden, NMA 0091188.

International collaborations are very fruitful, shedding light on what we too often assume on the basis of our location in the United States and offering new viewpoints on crucial questions about the present as well as the past. I have been amazingly fortunate in having Lena Sommestad as a collaborator and friend; we share socialist feminist values and enjoy tramping around old farms and villages imagining the lives of those who lived and worked there. She has been more generous with her time than many academics might have been, let alone someone who served as the head of the Social Democratic Women’s League, a Member of Parliament, and the governor of one of Sweden’s 21 counties. My life has been enriched by meeting many new colleagues in two countries where rural women’s history is not a marginal subject and sustainable and gender-equitable agricultural policies are national political issues.

Sommestad and I were able to carry out this project without any external funding. She worked on it during her summer and winter vacations from intensely demanding jobs; I worked on it between paid editing projects. Some of my plane trips were covered by frequent flyer miles I accumulated by charging non-travel expenses to a credit card, and most of my other research expenses were tax-deductible because I am self-employed as a freelance editor and independent historian. Lena opened many doors for me, and other people have also been generous with their time and expertise. Swedish and Norwegian colleagues have invited me to stay with them and shown me their favorite places in the countryside, often where their grandparents farmed. Librarians, archivists, and curators, who are surprised to meet an American with a Norwegian surname who is not tracing her ancestors, have been exceptionally helpful. Ordinary Scandinavians, who are notoriously laconic in public, have told me stories about their families’ rural roots in our shared Swenglish on long train journeys. All it takes to engage in such a project is a commitment to learning about a different society, a love of travel in unfamiliar places, and a willingness to set aside one’s status as a PhD who is a recognized authority on some topic in her own country and to sound like an ignoramus or a toddler while learning a new language and culture.

RWSA has many international members who participate in our triennial conferences. Whether they come from the Caribbean, Latin America, Europe, Africa, or Asia, most would be happy to have North American visitors, to share what they know, and to enlist you in helping their work to become better known here. Some US–based RWSA members already work internationally; for example, Valerie Grim has done collaborative work in sub-Saharan Africa and Brazil in addition to her research and advocacy with Black farmers in the US. The benefits for our international partners are clear; the rewards for us are immeasurable. In our interconnected world and shared global environment, it is vital that we no longer limit our thinking to what goes on within the borders of nation-states.

Pingback: January readings – Uneven Earth

Pingback: Agrarian Women and the Welfare State | Rural Women's Studies