Fruit of Her Fields: California Women Farmers at the Turn of the Century

Bethany Hopkins, University of California, Davis

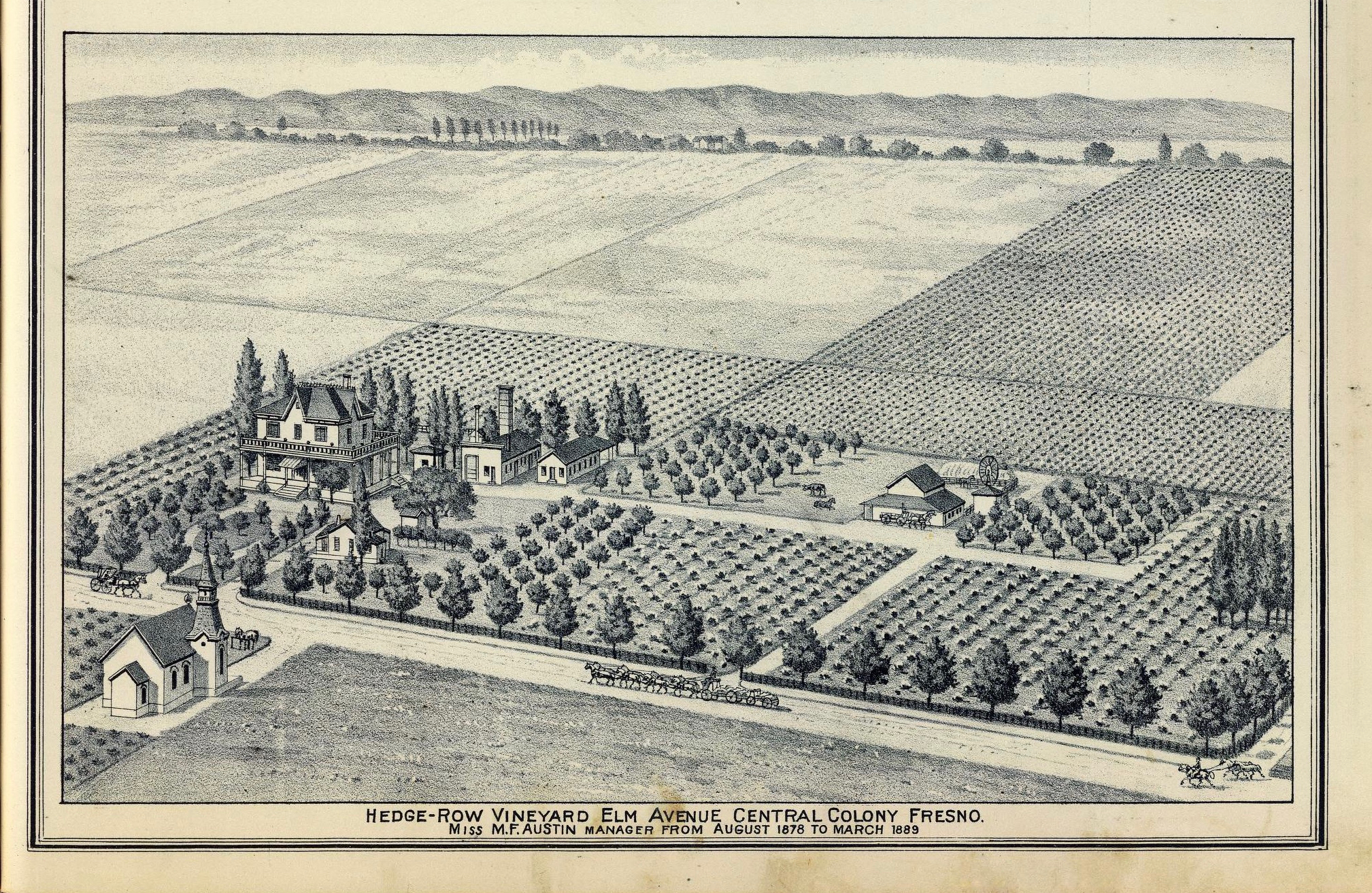

In 1876, four former schoolteachers bought 100 acres in Fresno, California. With Minnie Austin and Lucy Hatch at the lead, the women founded Hedge Row Vineyard to grow raisin grapes. A Sacramento Daily Union reporter praised them for starting a farm in “one of the most profitable branches of fruit culture,” and wondered if other women might follow their example.1

By the turn of the century, there was no need to wonder: California women had entered the ranks of specialty crop growers by the hundreds. By then, the Hedge Row women were being hailed leading the way into an industry where male farm ownership had been the rule. In 1899 orchardist Elise Buckingham called Austin a “woman pioneer” and declared “ her noble example opened the way for other women.”2

The story of Hedge Row and the women who followed became the basis for my doctoral dissertation, The Fruit of Her Fields: California Women in Commercial Horticulture, 1870-1915. These rural women illustrate two key trends in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century U.S.—the Anglo-American settling of the West and the expansion of American women’s rights. But they also reveal the uniqueness of California, where women (usually without husbands) embraced fruit growing with particular zeal. In my research, I identified three overlapping phenomena that help illuminate why.

Gender, Gardens, and the Press

First, California’s dominance in fruit and specialty crops gave rural women a way to make the nineteenth century gender stereotypes of domesticity work for their businesses, not against them. Garden imagery and a strong booster press made this possible.

To encourage Anglo-Americans to come out to California, boosters crafted a vision of the state Ian Tyrrell calls the “myth of the garden in the West.”3 In this myth, Anglo-Americans would harness California’s natural resources (sunshine, good soil, a mild climate) to start family farms. In the garden paradise, fruit farms would be both profitable and domesticated spaces. As garden boosterism blurred the lines between gardening and farming in the 1880s, the press promoted the idea that farming was perfect work for women. “It furnishes proper and plentiful exercise for both mind and body,” the Union wrote.4 “Horticulture and floriculture are especially adapted to women,” added Louise Houghton in The Pacific Rural Press— “and in no manner incompatible with their duties as wives or mothers.”5 In short, boosters touted California farming as healthy and feminine.

The press was a key site of garden booster rhetoric, and many successful female fruit growers took up the pen themselves. From Theodora Shepherd flower features Land of Sunshine to Minnie Sherman’s farm advice column in the California Cultivator, California rural women used the print public sphere to reinforce its message.

The press was a key site of garden booster rhetoric, and many successful female fruit growers took up the pen themselves. From Theodora Shepherd flower features Land of Sunshine to Minnie Sherman’s farm advice column in the California Cultivator, California rural women used the print public sphere to reinforce its message.

It helped, of course, that most were educated, well-connected, and white.

Race, Labor, and the Law

Second, California’s rural women succeeded as fruit growers because they were white women from the middle and elite classes. As women, they were given more leeway to side step race and labor issues plaguing male farm owners—and they did so just as the legal tide tipped more in their favor.

Asian men made up the majority of farm laborers in this time period—Chinese men in the late nineteenth century, and Japanese men in the early twentieth. Both groups faced a racist backlash from white Californians. White horticulturist women downplayed their reliance on Asian farm workers, highlighting the contributions of their children instead. Orchardist Georgie McBride said that she relied on her sons for labor, and “having raised her own help, she was independent of the unskilled Chinaman.”6 Seed farmer Theodora Shepherd formed a “woman’s stock company” with her daughters, even though her longtime Chinese employee Ah Wing was more of a true business partner.7 The garden booster myth depended on seeing a state that was as domesticated and beautified by white families —and in the public, farm women’ fictions often went unquestioned.

What’s more, barriers to white women’s land ownership in California decreased just as those for Asian men increased. In 1886, the federal government amended the Homestead Act to clarify that women who married during the five years they were proving up would not lose their land claim. Meanwhile, Congress passed Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (spearheaded by Californians), with wording that targeted Chinese farm workers. When Japanese laborers replaced them and moved quicker into farm ownership, California fired back with the Alien Land Act of 1913, barring all Asians (as “aliens ineligible to citizenship”) from owning land.

By then, California women had already gained the ultimate trump card—the right to vote.

The Women’s Movement

Finally, the rise of rural fruit farming women owed much to women’s organizations and women’s rights activists. Women’s clubs showed them the benefits of organizing along gender lines, and for the most political, woman suffrage was the final culmination of their farming endeavors.

Like other rural women in the 1880s-90s, California farm owners forged important social connection in women’s social and civil reform club work. But for female farm owners, clubs also provided business opportunities and cross-pollination with women’s rights activism. Friday Morning Club leader Caroline Severance of L.A. corresponded with nine of the state’s elite female horticulturists, offering them everything from professional introductions to business loans. In Fresno, Hatch was a leader in the Parlor Lecture Club, where she arranged activities like talks about the legal and social status of California women. And in 1900, elite dairy farmer Emma Shafter Howard founded the Women’s Agricultural and Horticultural Union of California (WAHU), a hybrid trade group and women’s club spanning the state.

Howard and other suffragist growers used WAHU to link the expansion of women’s farm enterprises to the expansion of the franchise. In 1905, WAHU and the California Promotion Committee produced a For California magazine issue highlighting the contributions of women’s farms. In 1908, WAHU president Minnie Sherman and suffragist Mary McHenry Keith got a meeting of men at the University of California farm to support the suffrage cause. When California women won the vote in 1911, the New York Times declared that the “women of California have won the ballot, and it was the farmers that gave it to them.”9

Just as the women of Hedge Row transformed from curiosities to lauded pioneers, women’s farm ownership took on greater meaning over time in California. By the turn of the century, their farms had become symbolic spaces—ones where women’s relationship to society, nature, and politics might be transformed.

1 “Women School Teachers Buying Fruit Farms.” Sacramento Daily Union, March 21, 1877.

2 Elise Buckingham. Quoted in Emma Shafter Howard, “Gardening as a Profession For Women,” in The International Congress of Women of 1899, Vol. 4, Women in Professions. (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1900), 156.

3 Ian Tyrrell. True Gardens of the Gods: Californian-Australian Environmental Reform, 1860-1930. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 2.

4 “Occupation for Women.” Sacramento Daily Union, June 20, 1885.

5 Louise Seymour Houghton. “Farming for Women,” Pacific Rural Press, May 19, 1888.

6 Georgie McBride. “A Woman’s Orchard,” in “Transactions of the Nineteenth Fruit Growers’ Convention of the State of California, San Jose, November 15-18 1892,” in Fourth Biennial Report of the State Board of Horticulture 1893-4 (Sacramento, 1894), 194.

7 Myrtle Shepherd Francis. “A Modern Flora.” Theodosia Burr Shepherd Papers, UCLA Special Collections MSS 123, Box 2, c. 1930.

8 Roger Daniels. The Politics of Prejudice. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 50.

9 “California Farmers Give Vote to Women.” New York Times, October 13, 1911.

Thank you for posting this summary of your research. I just finished a brief look at a female horticulturalist in South Dakota. There were some incredibly close parallels. She had a privileged background (comparably), she had an absent husband (the exact sequence of events for their break was unclear), and she was active politically. My subject even moved to California with her children after retiring and selling her property here, but I don’t know if she took up farming or politics again there. https://historysouthdakota.wordpress.com/2016/03/01/the-queen-of-orchardists/

Pingback: The Queen of Orchardists: Laura Alderman | History in South Dakota

Pingback: Welcome. | Bethany J. Hopkins