The Olive Garden Lady and Rural Middle American Culture

Cynthia Culver Prescott, University of North Dakota

Marilyn Hagerty was 85 years old when her long-running “Eatbeat” column in the Grand Forks Herald went viral. Within three days, her column received 400,000 hits – twenty times more than the next most popular story–and then hit 1 million. Urbanites across the United States pounced with snarky criticism, while other readers wrongly assumed that her review of a major Italian-style restaurant chain was a clever piece of satire. Why else would the newspaper in the state’s third-largest city, home to its flagship research university, publish a piece earnestly describing the experience of dining at a chain restaurant that had become shorthand for lowbrow culture?

Marilyn Hagerty was 85 years old when her long-running “Eatbeat” column in the Grand Forks Herald went viral. Within three days, her column received 400,000 hits – twenty times more than the next most popular story–and then hit 1 million. Urbanites across the United States pounced with snarky criticism, while other readers wrongly assumed that her review of a major Italian-style restaurant chain was a clever piece of satire. Why else would the newspaper in the state’s third-largest city, home to its flagship research university, publish a piece earnestly describing the experience of dining at a chain restaurant that had become shorthand for lowbrow culture?

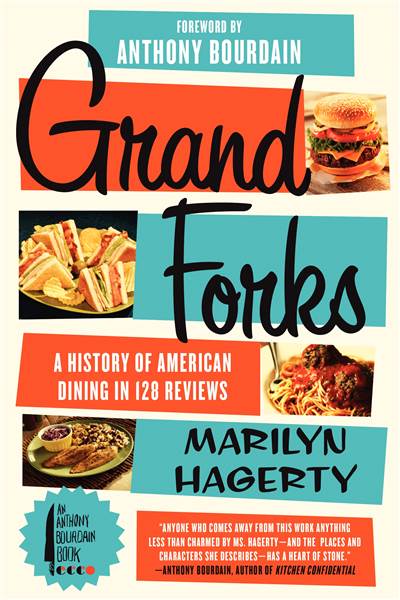

“The Olive Garden Lady,” as she became known, became an overnight media phenomenon. Readers across the country delighted or scoffed at her reviews of Ruby Tuesday and McDonalds. She appeared on Anderson Cooper, The Today Show, and judged a competition round on Top Chef. Celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain scored her a reservation at three-Michelin-star New York City restaurant Le Bernardin, and then contributed a forward to a new book-length compilation of Hagerty’s past “Eatbeat” columns, Grand Forks: A History of American Dining in 128 Reviews.

So why did Marilyn Hagerty “go viral” after more than fifty years writing for the same small newspaper with approximately 30,000 subscribers? While New Yorkers might have assumed Marilyn Hagerty’s Olive Garden review was a work of satire, her lively description of her first visit to Grand Forks’ newest restaurant was very much in earnest. Her readers in that town of 60,000—and particularly those in surrounding rural areas—might very well never have set foot in an Olive Garden before the Grand Forks location opened in 2012. And its opening was eagerly awaited by many local residents who were familiar with its reliably tasty food. Indeed, prior to its opening, I would sometimes dine at the nearest Olive Garden location when I was visiting the larger city of Fargo (population 120,000) some 75 miles away. Whenever I did, I would run into people I knew from Grand Forks. So popular was Grand Forks’ eatery that Hagerty waited several weeks before checking it out for herself and her loyal readers.

So why did Marilyn Hagerty “go viral” after more than fifty years writing for the same small newspaper with approximately 30,000 subscribers? While New Yorkers might have assumed Marilyn Hagerty’s Olive Garden review was a work of satire, her lively description of her first visit to Grand Forks’ newest restaurant was very much in earnest. Her readers in that town of 60,000—and particularly those in surrounding rural areas—might very well never have set foot in an Olive Garden before the Grand Forks location opened in 2012. And its opening was eagerly awaited by many local residents who were familiar with its reliably tasty food. Indeed, prior to its opening, I would sometimes dine at the nearest Olive Garden location when I was visiting the larger city of Fargo (population 120,000) some 75 miles away. Whenever I did, I would run into people I knew from Grand Forks. So popular was Grand Forks’ eatery that Hagerty waited several weeks before checking it out for herself and her loyal readers.

Hagerty’s review of the Grand Forks Olive Garden struck a cultural chord because the chain had become a touchstone in early-twenty-first-century American popular culture. According to Erin Gloria Ryan “Expressing a preference for dining at Olive Garden in 2012 … prove[d] a lack of cultural awareness to people who define themselves by being culturally aware.” It appeared on the list of Stuff White Trash People Like, and a competitor on ABC’s reality show The Bachelor lost her chance to marry the wealthy Firestone tire heir after identifying Olive Garden as her favorite restaurant.

Marilyn Hagerty’s guilelessness sets her apart from big-city culinary reviewers. Hagerty insists that she is a restaurant reporter, not a food critic. She intentionally avoids criticizing restaurants’ food, lest she damage the establishment’s business (or, one suspects, hurts the owner’s feelings). While this might seem absurd to foodies in New York City or Los Angeles, it makes a great deal of sense for a woman who grew up on the northern Plains during the Great Depression.

People in the Upper Midwest – and particularly rural women – have long valued strengthening community ties above individual fame. Neighborliness represents a core cultural value for rural Midwesterners like Hagerty. Farmers and farm women have long exchanged labor with the neighbors, weaving tight community webs. Those communitarian values persist today, even as high-priced high-tech equipment replaces physical labor in the fields and farm households increasingly rely on women’s off-farm labor to provide needed income and health insurance. After all, a neighbor’s assistance still might be the only thing that enables you to survive an unexpected blizzard. Moreover, as rural communities struggle to survive amid outmigration and the rise of big box stores and Amazon.com, their remaining residents hold fast to traditional cultural values. To publish a critical review of a local restaurant would be dangerously akin to Big City back-stabbing. Rural women might gossip amongst themselves, but they are expected to plaster on a friendly smile for outsiders. They must maintain a cheerfully united front in the face of an attack from the outside world. Thus for the Olive Garden Lady to critique the fruits of a chef’s labors would undermine not only her communitarianism but her femininity.

Of course Hagerty recognizes the difference between a McDonald’s Big Mac (her “secret sin”) and a four-hour fine dining experience at Le Bernardin. Her son James, who writes for the Wall Street Journal, explained to Minnesota Public Radio what regular Grand Forks Herald readers already knew: that if Hagerty devotes most of her column to describing the décor rather than the food, it indicates that she found little to compliment about the food. So if Marilyn Hagerty’s next “Eatbeat” column devotes more space to the quality of the napkins or than she does the cuisine, you might want to consider dining elsewhere. Unless, of course, you’re a foodie who embraces more exotic flavors. In that case, you might infer from Hagerty’s reporting that the newest ethnic restaurant in Grand Forks serves cuisine that is unfamiliar—and thus unappealing—to the town’s notoriously culinarily conservative food writer. But you’d do well to read carefully her reporting on the region’s best knoephla soup and tater tot hotdish. Whether you find her food reporting laughable or charming, you know that Marilyn Hagerty will remain true to her rural community values.

Thanks Team!

I love it! It is very important to keep reminding Americans

that there is more than one culture in this country — and they

are all important. Please forward to Cynthia, with my thanks.

Lou

Louis Galambos Research Professor, History; Editor, The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower; & Co-Director, The Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise, Johns Hopkins University. The Creative Society — and the price Americans paid for it, Cambridge University Press, 2012. Co-editor, Noncommunicable Diseases in the Developing World: Addressing Gaps in Global Policy and Research, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. Eisenhower: Becoming the Leader of the Free World Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018 ________________________________

Thanks, Louis!

— Cynthia Prescott