Farm Institutes and Rural Women:

The Case of Rural New York State

Mary Ellen Zuckerman, SUNY Brockport

Introduction

As the need for improved methods of agriculture methods spread across the United States in the late nineteenth century, various mechanism emerged to educate and share information among farm families. Day or week-long Institutes were one of the first type of activities created to take on this function. Initially organized locally, eventually state departments of agriculture took on the oversight of these Institutes. Later, in some states, including New York, agricultural colleges gained control over institutes, often drawing them in to their own campuses, rather than supporting the events across states. However, the decentralized institutes, as well as the administration by the agriculture school, laid the groundwork for the county-based agricultural extension services for farm families created under the federal Smith–Lever Act of 1914.

As the Institutes gained in popularity, they began devoting sessions to women’s interests. By the early twentieth century, some states, including New York, developed separate institutes targeted at farm women and their needs. While these segmented meetings didn’t always continue past a year or two, they established a firm basis for the home economics branch of the extension services authorized by the Smith–Lever Act.

Educating Farm Families in late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century United States

In the decades after the Civil War, state agricultural societies, federal and state governments, and business interests began focusing on the need for improved methods of farming, and a means for educating farmers about the most productive and efficient ways to manage their farms. Initially patterned after teachers training institutes which were popular in the post Civil war years, farmer’s institutes began appearing, particularly in the mid-west. Experienced and respected farmers as well as faculty from the land grant institutions, many of them created under the provisions of the federal 1862 Morrill Act, lectured, served on panels and demonstrated techniques and equipment at these institutes, as well as distributing informational bulletins. These gatherings were hosted in various locations around a state, scheduled at times convenient for farmers. Some institutes lasted a day, others several days. The goal was primarily educational, although inevitably it was social as well with participants enjoying food and entertainment. In early years, the experienced farmers held more sway with audiences as speakers, but as time went on the scientific information that academic experts could share and show to be successful gained credibility. Scientists identified ways they could help farmers increase their output with better seeds and crop rotation, improved strains of cattle and more reliably produce food for the nation. Eventually they also tried to teach some business principles, particularly marketing and distribution.

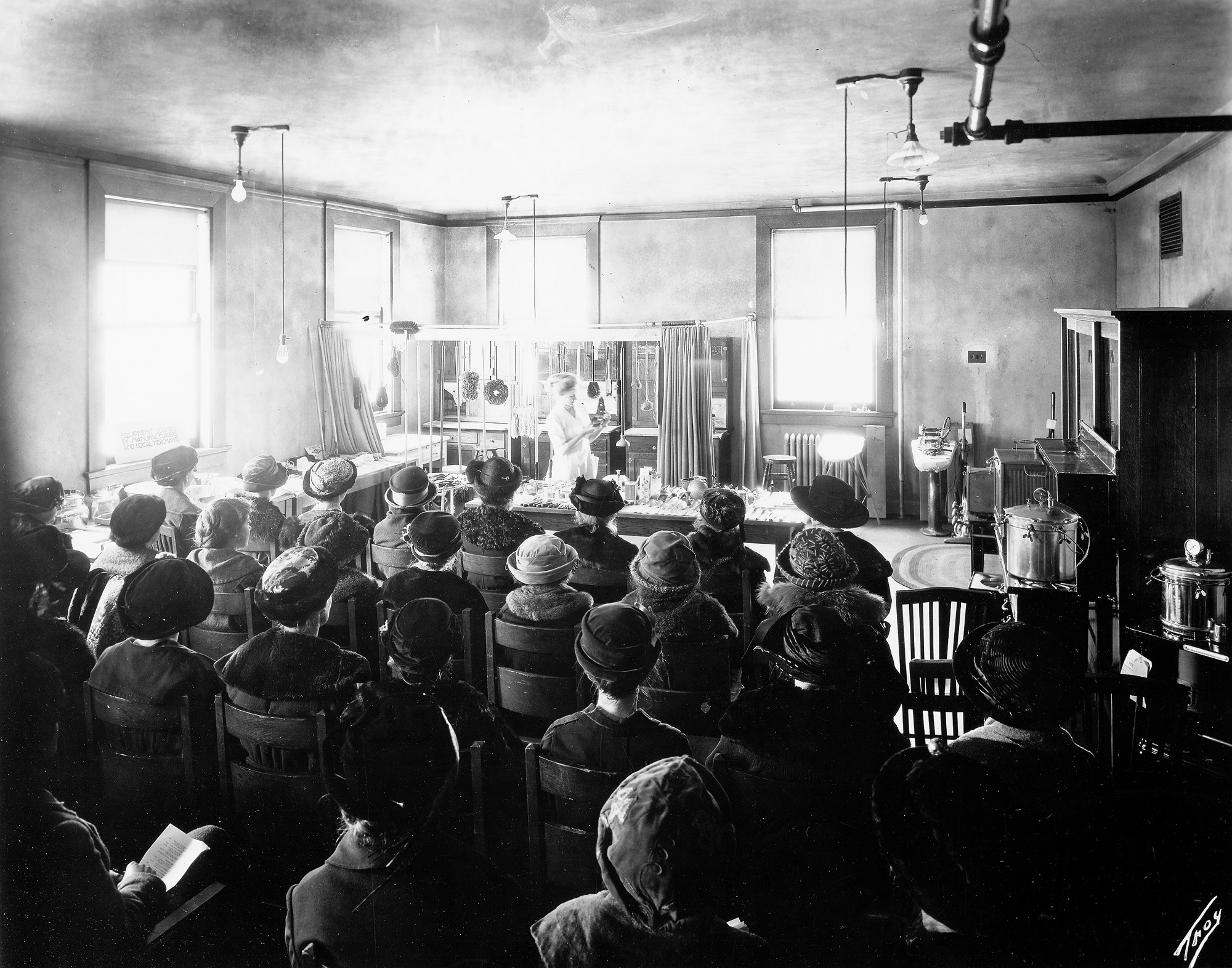

Demonstration of home conveniences by Ruth Kellogg during Farmers Week, circa 1921. (Troy Photo/Div. Rare & Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library) https://timeline.com/home-ec-actually-fostered-trailblazing-female-scientists-7f0fdcafa89

By the early twentieth century the farm institutes were quite common. Farmers who could not take a four year degree or even take a short six week winter course, could get away for a week to meet with other farmers and with experts in agriculture. Between 1880 and 1890, farmers’ institutes or their equivalent had appeared on a fairly regular basis in 26 states; in 1891, 14 states allocated monies to support them.[i] Meetings were advertised through mailings, programs and notices in local papers. Local communities had responsibility for arrangements such as speaking venue, publicity and arranging for hospitality for the lecturers. Meetings often took place in the local Grange and Grange members played a key role in getting audiences and publicity for the local farm institutes.

The institutes reached the height of their popularity in the early 1900s. The Institutes were set up either by the state Departments of Agriculture or the agriculture schools and/or experiment stations. By 1914, one source cites that over 8,000 such institutes were held annually and estimated that more than 3 million people attended.[ii]

Women’s sections and speakers had been taking place at these institutes, especially in the west, as early as the 1890s. In Wisconsin women were involved in the institutes from their beginnings and included sessions on “butter making, the dairy, fastening ends and binding edges, and education of farmers’ daughters.”[iii] Other schools held similar events. For example, the University of Wisconsin reported to the seventh Lake Placid Conference in 1905 that a ten day housekeeper conference had been held, with much success. A Housekeepers Conference, complete with a model kitchen, had been held at the University of Missouri. Iowa, Kansas, Colorado, Wisconsin, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland and Nebraska all engaged in activities to bring information about better homemaking techniques to rural housewives in the years immediately after the turn of the century. Sometimes the women’s portions were called “cooking schools, and food preparation.” Other topics typically covered included “labor-saving devices, better sanitary conditions, better methods of preparing and preserving foods, care of the sick, and beautification of the home.”[iv] Following the example of the province of Ontario in Canada, some women’s institutes charged registrants a small sum (25 cents) to become part of the organization. One newspaper covering a women homemaker’s institutes called the expert lecturers “Goddesses of the Household.”

Demonstration of housekeeping equipment by Ruth Kellogg at Farmers Week, 1921. (Troy Photo/Div. Rare & Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library) https://timeline.com/home-ec-actually-fostered-trailblazing-female-scientists-7f0fdcafa89

At least 15 states offered home institutes as early as 1903, as state agricultural bureaus sought to reach farm women. Holding sessions in conjunction with the farm institutes their husbands were attending made practical sense.[v] By 1909 four states (including New York) had held full institutes devoted just to women, comprising 145 sessions.[vi]

Farmer’s Institutes generally moved to a national level with the 1896 organization of the American Association of Farmer’s Institute Workers in Watertown, Wisconsin. By 1901 the federal government had recognized the important of these institutes for men and women , with the United States Department of Agriculture’s Office of Experimental Stations appointing a farmer’s institute specialist, taking on the publication of their annual bulletin and preparing information and booklets to educate institute lecturers across the nation, providing them with more comprehensive and up-to-date material than they may have had. As best practices or successful work and publications emerged in various states, the national office served as a coordinating unit and would disseminate this information out across the states.

Targeting farm women was deemed one such best practice, and the federal office of experiment stations created a booklet laying out ways to develop and run such homemaker targeted institutes. Suggested sessions included ones on “domestic and sanitary science, household arts, laborsaving appliances and conveniences, social enjoyment, and self-improvement.”[vii] Guidance for running institutes started in the early part of the century and grew so that by 1913, 66 trainings were held in 16 states.

Railroads supported all these institutes, offering special rates to attending farmers and their families. Trains were also used in demonstration work, becoming so popular that by 1906 they had run in 21 states. With enticingly descriptive names such as the “corn” special, the Opportunity Special, the Diversified Special and the Alfalfa Special, these fully equipped demonstration units showing both farming and housekeeping techniques and equipment attracted widespread attention, particular in the West, Midwest and South, bringing information to farm families. One railroad car in North Carolina showed a fully equipped kitchen with working appliances such as stove, sink, oven and ice box. It was said that the need for this particular car developed from the popular housekeeping institutes that had been held across the state, 21 by 1906.[viii] In New York State, Cornell equipped such trains, sending out five in 1909-1910, reaching about 30,000 people over four railroad lines. Lecturers traveled on the trains, bringing expertise and up-to-date techniques to the men and women of New York.

Demonstration train car, 1919. (Troy Photo/Div. Rare & Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library) https://timeline.com/home-ec-actually-fostered-trailblazing-female-scientists-7f0fdcafa89

The railroad companies partnered with the agricultural schools out of self interest, believing that bringing farmers to institutes as well as sending out demonstration trains would all increase agricultural production, which then had to be shipped over the rails. [ix]

The 1914 passage of the Smith Lever Act and the ensuing experimental and demonstration activity lessened the emphasis on Farmer’s institutes and the national organization ended in 1919.[x] But while they were taking place, such institutes generally met information and technical needs for rural farm families, provided an excellent venue for communication and created an appetite and a market for goods, equipment and conveniences on the farm.

Bibliography:

Craig, Hazel Thompson ( ). The History of Home Economics.

Holt, Marilyn Irvin (1995). Linoleum, Better Babies & The Modern Farm Woman, 1890-1930. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Moss, Jeffrey W. and Cynthia B. Lass. “A History of Farmer’s Institutes,” Agricultural History, Vol. 62, No.2(Spring 1988), pp. 150-163.

Prawl, Warren, Roger Medlin and John Gross (1984). Adult and Continuing Education Through the Cooperative Extension Service. Columbia MO: University of Missouri Press.

Rodgers, Andrew Denny III (1965). Liberty Hyde Bailey. NY NY: Hafner Publishing.

Seevers, Brenda, Donna Graham, Julia Gamon and Nikki Conklin (1997). Education Through Cooperative Extension. Albany NY: Delmar Publishers.

True, Alfred Charles (1928). A History of Agricultural Extension Work in the United States, 1785-1923. Washington, DC: US GPO.

[i] True, p.14.

[ii] Quoted in Prawl, et al, p.15.

[iii] True, p.17.

[iv] True, p.p.37.

[v] True, p.18; Seevers, et al, p. 34.

[vi] Moss and Lass, p.160.

[vii] Ibid, pp. 160,161.

[viii] True, pp.28, 38; Holt, pp 26-28; Craig, p.24.

[ix] Holt: p. 27, 28.

[x] True, pp. 22-25, 28, 33.