In honor of the upcoming thirty-fifth anniversary of Joan M. Jensen’s publication of her landmark collection of primary documents,With These Hands: Women Working on the Land (1981), the Rural Women’s Studies Association sponsored a roundtable highlighting innovative uses of primary sources for studying rural women at the 2015 annual meeting of the Agricultural History Society in Lexington, Kentucky. This panel showcased recent research and discussed the unique sources employed to investigate the diversity of women’s experience in the rural United States and Canada. Today we are featuring the work of one of those accomplished scholars, Jodey Nurse-Gupta. Stay tuned for future installments in this series, “Sources in Rural Women’s History.”

These Hands Crafted Fine Things: Material Culture in Rural Women’s History

by Jodey Nurse-Gupta, University of Guelph

Figure 1: Sarah Jane (Wheeler) Jackson, “Sock,” circa 1900, 2004.14.5.02, Wellington County Museum and Archives.

Joan Jensen outlines in her seminal study of rural women, With These Hands: Women Working on the Land, that finding documentary sources on rural women is not always an easy task. Despite this, however, she and others have uncovered and utilized various documents to reveal the real life experiences of rural women.[1] When I began studying female fair exhibitors, I believed written sources would shed light on their experiences. My hypothesis was that women’s exhibits would provide a strong indication of what types of material goods were important to women, and because fairs were important venues for individual and communal expressions of values, I believed women’s work could also reveal nineteenth- and twentieth-century rural society’s esteemed attributes. Initially, however, I was interested in things, not artifacts. By that I mean I was interested in analyzing the lists of things women exhibited at fairs, lists I could find easily in fall fair prize books and newspaper reports. But as I delved into these and other written sources, I could not locate the voices of female exhibitors. I often read what others thought of the “ladies’ work,” but by and large I could not find the voices of the women themselves. Fortunately, while researching I came across several objects that would become important sources for my research.

Before I discuss these objects, I should explain that I was among those students of history who needed to, rather than wanted to, integrate material culture into my study of the past. The idea of investigating material culture was intimidating. I had not worked with artifacts before and I believed that the “connoisseurial” skills needed to investigate them, the ability to detect and understand the minute details of the objects themselves, were beyond my ability.[2] Learning from things can be difficult because of the complexity inherent in objects as sources. Artifacts are tools, but they are also “signals, signs, and symbols,” and their meaning is often subliminal and unconscious.[3] Material culture is also an interdisciplinary study that employs a wide range of approaches that highlight the multi-faceted nature of material culture, and the thought of participating in this discussion was daunting.[4] Luckily, I found my bearings in this field of study after reading Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s acclaimed book, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth. Thatcher Ulrich’s use of individual objects to find deeper personal meanings and her ability to reconnect them to their historical contexts so that we can better understand their social, cultural, and economic importance was enlightening.[5] I was inspired by discovering how objects could improve our understanding of the everyday lives of people in the past.

Figure 2: Sarah Jane (Wheeler) Jackson, “Nightgown”, circa 1900, 1954.97.1, Wellington County Museum and Archives.

I especially came to appreciate the usefulness of objects as sources when I discovered my first two women’s fair exhibit artifacts, a pair of finely knit fancy children’s socks and a woman’s cream-coloured wool flannel nightgown with embroidered trim [Figure 1 and 2]. These items were made around the turn of the twentieth century by Sarah Jane Wheeler Jackson, who was born in 1856, and married an area farmer, David Jackson, in 1872. The Jackson’s were life-long residents of Erin Township and active participants at the Erin Fair;[1] Sarah herself is said to have shown her handiwork and cookery there for over 57 years.[2] Sarah made these items roughly 115 years ago, and the use of purchased fabric and yarn, machine stitching, and handsewn embroidery and knitting testify to the ways in which rural women consumed and produced in order to clothe their families and furnish and decorate their homes. Both items show no sign of wear and the care with which they were crafted and maintained undoubtedly suggests both pride in their creation and strong sentiment to the meaning behind them.

The ability to fashion clothing was passed down from Sarah to her daughter Clara Jackson Robertson, who, like her mother, left behind evidence of the family tradition of exhibiting at fairs in the form of a blue cotton men’s work shirt [Figure 3]. The work shirt was made in 1925 and shown at the Erin and Acton Fall Fairs that year. Clara was an accomplished seamstress and quilter who won many prizes for her quilts and clothing, as well as baking and fancywork.[3] For Clara, the homemade shirt represented a number of things. As a seamstress, sewing was a marketable skill, and the shirt illustrated her proficiency in this line of work. The fact that the shirt was shown at fairs demonstrates the value Clara placed on presenting her work for public consumption, but it also illustrates a desire to maintain the family tradition of participating at these events.

Figure 3: Clara (Jackson) Robertson, “Shirt, Work,” circa 1925, 1994.34.1, Wellington County Museum and Archives.

My interaction with these initial objects led me to consider new aspects of my work. I realized that there is perhaps no greater testament to the meaning of women’s handiwork than the examples of how this work was cherished by the women who made them, as well as by their family members long after they were gone. Material possessions are often kept as a reflection of self-identity, hold rich biographical meanings, and help women to tell the stories of their lives.[4] The protection these objects received over the years encouraged me to consider the pleasure they elicited and the memories they contained. My interaction with objects made me value what things could tell me about “meaning making, identity formation, and commemoration.”[5]

Certainly there are many things that objects cannot tell us, but the individual meanings objects create and convey are exciting for historians studying rural women because they offer a chance to interpret their experiences and identities more deeply than would otherwise be possible. The varied approaches to material culture that I initially found so intimidating have also proven useful, even when less successful. For example, in an attempt to gain the sensory experience of creating a prize winning handicraft exhibit, I enrolled in a knitting course that left me with a half-finished scarf and a half-finished tuque; it is then that I realized I would likely never experience the emotion one would feel for an expertly crafted item adorned with a first prize ribbon. Still, I appreciated the skill and creativity of female exhibitors’ domestic work and handicraft all the more for the experience. And of course, the objects you discover also make you consider all of those objects you could not find. Most women’s fair exhibits do not end up in museums. This does not mean that they were not valued, but rather that they were given away as cherished gifts, well used in the home until beyond repair, or worn with pride by their creators until, perhaps, they were a little worse for wear. Many more remain in the hands of family and friends, considered more valuable as family heirlooms than community artifacts.

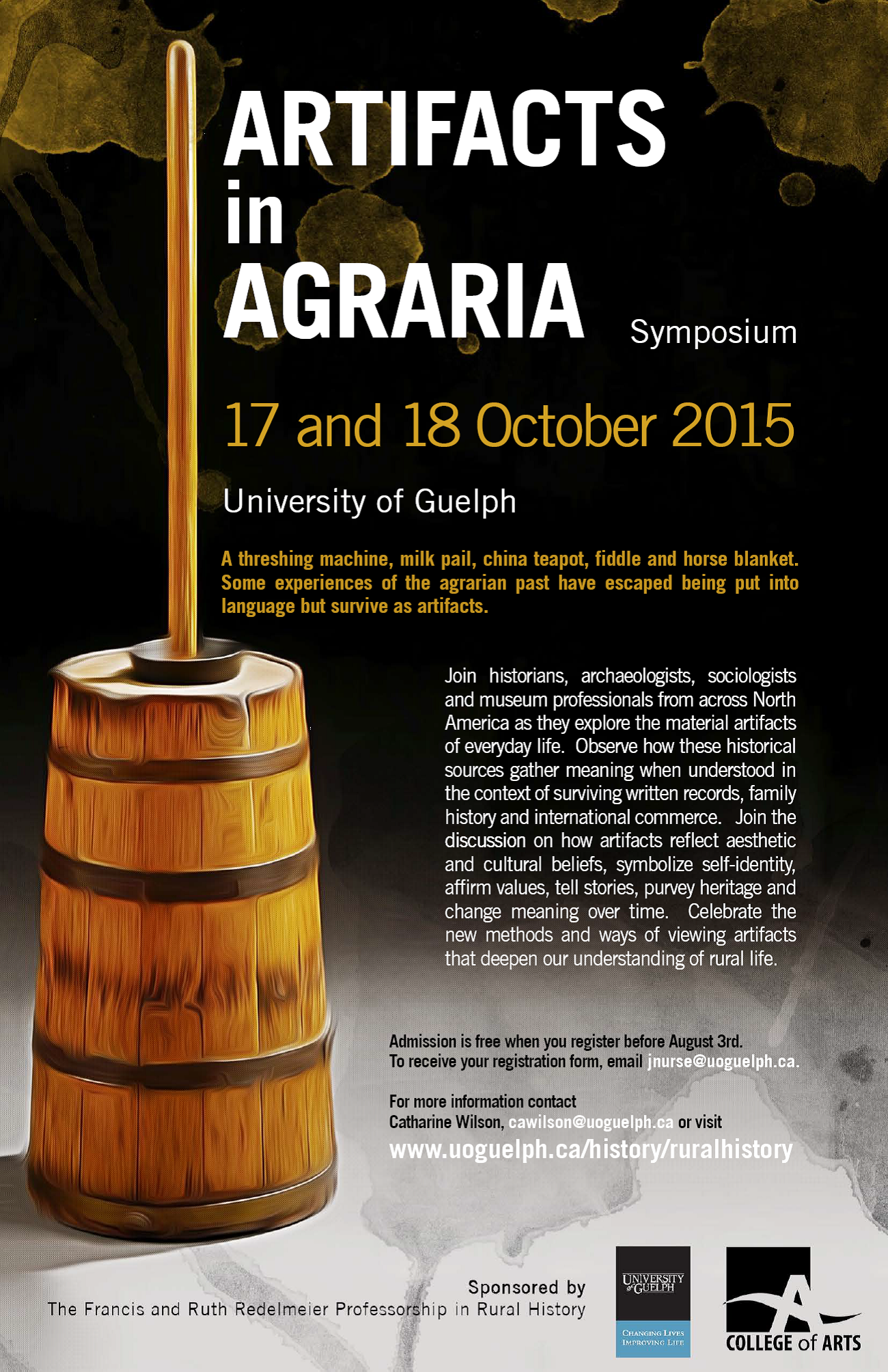

I have come to truly appreciate what objects can tell us about people, about their lives, how they were remembered, and how they wanted to be remembered. My newfound passion for objects encouraged me to assist in the organizing of a symposium, to be held this fall, entitled “Artifacts in Agraria,” in which historians, archaeologists, sociologists, and museum professionals from across North America will come together to discuss artifacts that deepen our understanding of rural life. For historians’ studying rural women, where sources can be harder to come by, I believe objects are crucial sources for helping to uncover rural women’s lives and identities.

I have come to truly appreciate what objects can tell us about people, about their lives, how they were remembered, and how they wanted to be remembered. My newfound passion for objects encouraged me to assist in the organizing of a symposium, to be held this fall, entitled “Artifacts in Agraria,” in which historians, archaeologists, sociologists, and museum professionals from across North America will come together to discuss artifacts that deepen our understanding of rural life. For historians’ studying rural women, where sources can be harder to come by, I believe objects are crucial sources for helping to uncover rural women’s lives and identities.

[1] For example, at the 1901 Erin Fair, Sarah Jackson won six first or second prizes in the “Ladies’ Work” section of the Domestic Department, mainly for knit items. Jackson appeared on the prize list winner reports into the 1930s.

[2] “Account Ledger: 1889-1899,” Erin Agricultural Society fonds, A1989.97, Reel 6; and provenance description for Sarah Jane (Wheeler) Jackson, “Nightgown”, circa 1900, 1954.97.1, Wellington County Museum and Archives..

[3] Provenance description for Clara (Jackson) Robertson, “Shirt, Work,” circa 1925, 1994.34.1, Wellington County Museum and Archives.

[4] Kathleen Cairns and Eliane Leslau Silverman, Treasures: The Stories Women Tell about the Things they Keep (Alberta: University of Calgary Press, 2004), xii-xiii.

[5] Beth Fowkes Tobin and Maureen Daly Goggin, “Introduction: Materializing Women,” in Women and Things, 1750-1950: Gendered Material Strategies, eds. Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009), 1.

Pingback: Rural Women and their Things: Thoughts on the 2015 Artifacts in Agraria Symposium | Rural Women's Studies