Jennifer Helton, Ohlone College

Jennifer Helton is Assistant Professor of History at Ohlone College in Fremont, California. She has written on the history of the woman suffrage movement in the west for a variety of outlets, including High Country News, WyoFile, and the National Park Service. Her essay on suffrage in her home state of Wyoming appears in Equality at the Ballot Box, an anthology published by the South Dakota Historical Society Press in 2019.

In 1875, the suffragist and feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote, “We are in the midst of a social revolution, greater than any political or religious revolution, that the world has ever seen, because it goes deep down to the very foundations of society. . . . Conservativism cries out we are going to destroy the family. Timid reformers answer, the political equality of woman will not change it. They are both wrong. It will entirely revolutionize it.”[1]

Today, the idea that women should vote and hold public office is, for the most part, no longer scandalous in the United States (though women are still under-represented in U.S. politics, at all levels). But in the nineteenth century, support for woman suffrage was a radical stance. Suffragists were accused of being “unwomanly” and “unsexed,” of seeking to destroy basic structures of society.

The American West was the first region of the United States to grant suffrage to its women. As a historian of the western suffrage movement, I have always wondered what inspired ordinary women to join this revolutionary cause. And as someone who grew up in small rural towns, I have always been intrigued by the strong support of rural areas for suffrage. In rural communities, where everyone knows everyone else’s business, adopting radical ideas can expose one to judgement, perhaps even censure. So how did rural western women find the courage to support suffrage?

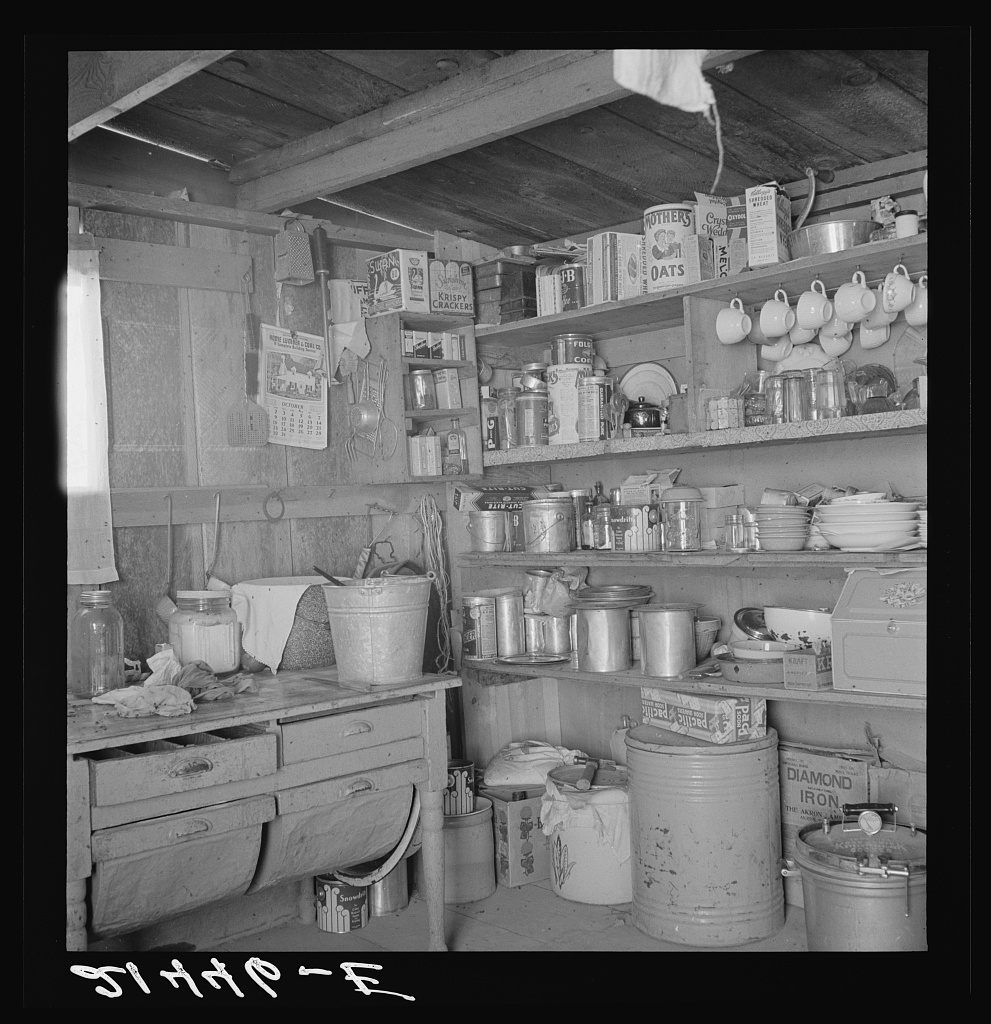

The theme of this year’s Rural Women’s Studies Association conference was Kitchen Table Talk to Global Forum. This theme prompted me to think about the role of the kitchen in the rural suffrage movement. Consider the possibilities of a kitchen table as a site of radicalization. We think of the nineteenth-century kitchen as women’s space, but the reality was more complicated. Western settler colonial communities rejected the values of the Indigenous societies of the West; in many of those societies women held authority and status. But when EuroAmericans came west, they brought their gender roles and legal structures with them. One aspect of this was the legal doctrine of coverture. Under coverture, women’s legal rights transferred to their husbands when they married. These rights included property ownership, the ownership of one’s wages, the ability to open a bank account, and laws relating to marriage and inheritance. Thus, in the EuroAmerican tradition, even though the kitchen was seen as women’s domain, a married woman did not actually own her own kitchen table. Nor did she have the right to profit off of the work she did at it.

Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division https://lccn.loc.gov/2017773855

This had important consequences for many rural women. Farm women commonly made butter and sold eggs to earn money for the family. Abigail Scott Duniway, one of the most important of the western suffrage leaders, described how she made “thousands of pounds of butter every year for market” in addition to her other wifely and childrearing duties, which included “to sew and cook, and wash and iron; to bake and clean and stew and fry; to be, in short, a general pioneer drudge, with never a penny of my own . . .” She reported that her butter and egg money paid “for groceries, and to pay taxes or keep up the wear and tear of horsehoeing, plow-sharpening and harness-mending.”[2]

Though family expenses sucked up all of her profits, Duniway’s husband supported his wife’s business endeavors and mostly allowed her control of them. But not all husbands of the era did; nor did the law compel them to. Farm women were not legally entitled to keep their earnings. Though they had produced and marketed the goods with their own labor, a husband could take the profits any time he liked – and many did. Duniway recorded a case of a nursing mother, whose older children needed new waterproof suits (a necessity in the Oregon winter). The mother promised she would sew the suits if the children made enough butter to pay for the fabric. Over several months, they did. But her husband took their butter money and used it to buy a racehorse instead. The children did not get their suits, and the mother was powerless to do anything about it.[3]

Rural women also used their kitchens to make money by taking in boarders. Duniway writes of a woman whose husband abandoned her and their five small children. A male acquaintance loaned her $600, and she rented a building and started a boarding house. But just as she began to get back on her feet, her husband returned, took what little money she had, and left her broke – again. Moreover, the acquaintance never recouped the $600 loan, since the woman legally had no right to make a contract with him. Eventually the couple divorced, and in the ensuing poverty, the woman was unable to keep her family together. The children were scattered to other homes.[4]

Cases such as these are what drove Duniway to become a suffragist. She believed that if women had the vote, they could change the laws that created these situations.[5] When I read the letters and diaries of early suffragists, these are the recurring themes that seem to bring women into the movement. A drunken or unfaithful husband, an ugly divorce, the inability to claim a deceased husband’s property – these are the experiences that drove many women to suffrage activism. So is concern for the women who, unable to make ends meet, turned to prostitution to pay their bills.

Almost 150 years later, the political and social revolution that Stanton predicted is ongoing, though much has changed. But we should remember that for many of our ancestors, the spark for that revolution began at kitchen tables – tables at which women worked, but which they did not control.

[1] ECS, “Home Life,” in Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Ellen Carol DuBois, and Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Correspondence, Writings, Speeches, Studies in the Life of Women (New York: Schocken Books, 1981). P. 132.

[2] Abigail (Scott) Duniway, Path Breaking: An Autobiographical History of the Equal Suffrage Movement in Pacific Coast States, 2d ed, Studies in the Life of Women (New York: Schocken Books, 1971). 9-10.

[3] Duniway 21-22.

[4] Duniway 23-24.

[5] Duniway. 37-39.