The Burn and the Glow: Writing the Honest Appalachia

Natalie Sypolt

West Virginian, writer, editor, and Assistant Professor at Pierpont Community & Technical College

Artists, especially from places like Appalachia–my home–must always walk a consciously fine line. While it is our job as writers, painters, play-makers to push the boundaries, make people think, and disrupt the norms, we must also also contend with the baggage that comes with being from a place that, for generations, has been portrayed in most media as backwards, ignorant, and even dangerous. We are the easy punchline to the offhanded joke. We are the face of rural poverty. We are the scapegoats.

Artists, especially from places like Appalachia–my home–must always walk a consciously fine line. While it is our job as writers, painters, play-makers to push the boundaries, make people think, and disrupt the norms, we must also also contend with the baggage that comes with being from a place that, for generations, has been portrayed in most media as backwards, ignorant, and even dangerous. We are the easy punchline to the offhanded joke. We are the face of rural poverty. We are the scapegoats.

Presenting one’s place in a truthful and honest way while making sure not to perpetuate the harmful stereotypes that have, for so long, told everyone outside of our region who we are, is sometimes a daunting job. Even more importantly, as we know, the true danger of the “one story” is not just simplifying a culture to “one story” for outsiders, but telling that story so often and so consistently that insiders also start to believe that story about themselves.

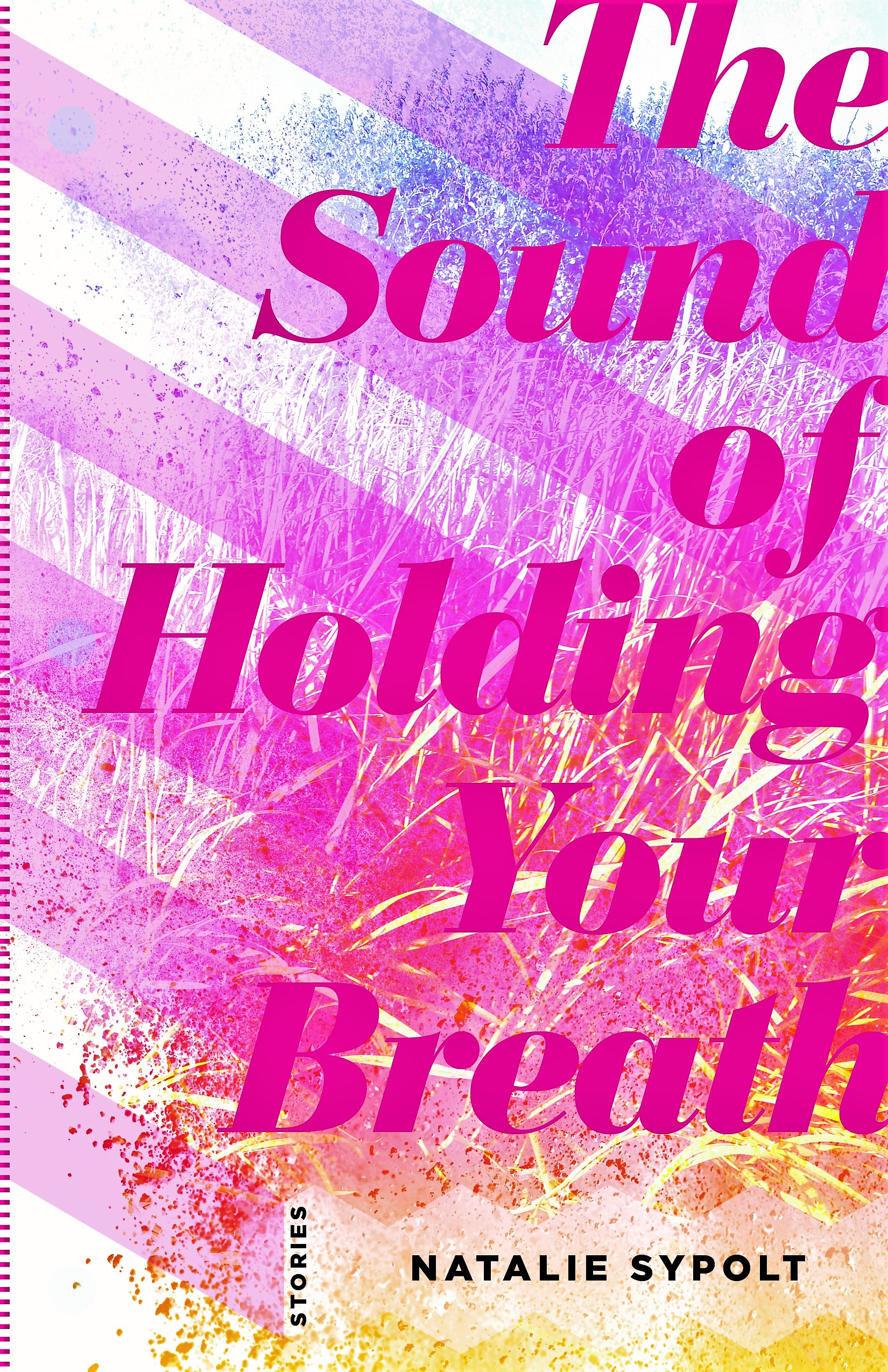

Since the publication of my first book, The Sound of Holding your Breath, a collection of short stories set in West Virginia, I have had to consider the question of representation many times. Interviewers have asked me about my decision to set my stories in WV (and I have to say that it wasn’t really a conscious decision–this is my place; why shouldn’t I set my stories here?) and some reviewers have written that the place I write about is full people in turmoil and conflict, violence and struggle. I have accepted that these statements are not necessarily wrong, and when I jokingly said that my stories were a little “murdery”, it wasn’t really a joke. But I did not set out to write about violence; to me the stories are about friendship, family, perseverance, resistance, and, ultimately, love. Can a story be both a love story and a mystery? A story of a relationship and of a murder? I think all the best stories are.

Since the publication of my first book, The Sound of Holding your Breath, a collection of short stories set in West Virginia, I have had to consider the question of representation many times. Interviewers have asked me about my decision to set my stories in WV (and I have to say that it wasn’t really a conscious decision–this is my place; why shouldn’t I set my stories here?) and some reviewers have written that the place I write about is full people in turmoil and conflict, violence and struggle. I have accepted that these statements are not necessarily wrong, and when I jokingly said that my stories were a little “murdery”, it wasn’t really a joke. But I did not set out to write about violence; to me the stories are about friendship, family, perseverance, resistance, and, ultimately, love. Can a story be both a love story and a mystery? A story of a relationship and of a murder? I think all the best stories are.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the way I have represented women characters, both in my current book of stories, and in the one that I am writing currently. I want to portray the Appalachian woman in all her complexity–her toughness, resilience, and intelligence–while also admitting that sometimes the Appalachian woman–like all women–makes bad choices, lives a hard life, sacrifices in ways both small and profound for her family. The trick, I think, is to not make her a victim, even if she is victimized. Terrible things happen; the way that characters–and people–react to those things show who they truly are. Hopefully that will be a person who does the very best she can, even if sometimes that isn’t the thing the rest of the world would see as the “right” thing to do.

When I was a kid, I remember hearing this story of a witch who was buried in the cemetery we used to visit because my grandma’s brother was buried there. Her marker was plain and stark white and when the orange sun was setting, it would hit that stone in such a way that made it look like it was on fire. I had seen that myself and thought it one of the scariest things I’d ever witnessed. The story went that Norie–that was her name–that Norie’s husband would get drunk and beat her and knock her off the high porch in front of their little shack. Instead of screaming or crying, she would start singing, and the singing would make her husband stop. I don’t know what she would sing–I guess I never thought to ask–but now I really wish I knew.

I remember once asking my pap about Norie. I figured if anyone would know about the witch, it’d be him. He knew all the good stories. He just shook his head though and said, “She wasn’t no witch, just a poor old woman who got beat by her husband.” I felt dumb, and small, because of course that was the answer. And the truth was that Norie wasn’t a witch, but was a woman who knew her situation, knew what was coming, and figured out a way to survive it. She wasn’t a perfect woman, but she was a real one.

If no one had told me that she was a witch, maybe I would have seen that light on her grave marker as an angelic beam instead of a scary fire.

Appalachia, too, is both a beautiful mountain glowing with the sun and a scorching fire. Artists must, I believe, be willing to represent all sides of this complex place, and to do it in a way that does not hold back out of fear. Honest is all that we can be. Sometimes honesty is not the nice or beautiful thing, but I hope it is always the best thing.

As a native Arkansas Delta native, I have a feeling I would love your stories on the Appalachian woman. In spite of our different ethnicity, I’m sure we share some of the same stereotypes. Best to you, and keep on telling your region’s stories!

Thanks for your comment, Janis! I’m sure you’re right.

Thought provoking.

Dern. You read my mind. I’ve been thinking about telling the truth, what that means, and its ever-scary consequences. Usually — always? — worth it.