Gary Gillman, Beer Et Seq

Toronto, Ontario, Canada `

In North America in the late-19th and early 20th centuries, manufacturing and wholesaling firms relied on armies of traveling sales personnel to interest buyers in their product line. Their customers were typically retail store owners and sometimes the ultimate consumer, say the “private clients” of a drummer selling an upmarket line of clothing or accessories.

In the vernacular of the day these peripatetic vendors often were termed “drummers”. While the noun form is obsolete, the cognate expression “to drum up business” recalls this older term. Usually, although not invariably, the commercial traveler was male. The occupation assisted to supply thousands of dry goods, jewellery, hardware, boot and shoe, clothing, tableware, grocery, and other small merchants spread across the nation. Although a drummer’s sales “territory” might encompass localities of any size, it classically covered medium-size and smaller towns and their hotel culture, viz. “corridors” and smoking rooms, dining rooms and bars, and sample rooms, to exhibit products to merchants.

So common yet noteworthy were drummers, they became a stock figure of American culture. Newspapers and magazines often profiled them, frequently to humorous effect. Their emblems were a flashy style of dress, volubility, a quick joke and wide smile, a cigar, and railroad schedule. With the onset of more sophisticated methods of advertising and the department store in larger urban centers, the drummer’s role lessened in importance, but continued in the business system, nonetheless.

Business and social historians have studied the drummer phenomenon, for example Walter A. Friedman in his (2004) The Birth of the Salesman: The Transformation of Selling in America. Friedman usefully distinguished commercial travelling from peddling, canvassing, retailing in a shop, and other forms of product merchandising. See also Timothy B. Spear’s (1995) 100 years on the Road: the Traveling Salesman in American Culture, and Susan Strasser’s “The Smile That Pays: the Culture of Traveling Salesmen”, a chapter in (1992) The Myth-Making Frame of Mind: Social Imagination and American Culture, James B. Gilbert, editor.

Between about 1880 and the onset of World War I, the general American press and trade journals, as well as fictional treatments and both stage and film productions, gave increasing attention to a small subset of the drummer class, the female drummer.

Like her male counterpart she was typically in her twenties or when seasoned, thirties, as any drummer past 40 was viewed as expendable by the employer due to presumed reduced vigor and ability to withstand the rigours of the road.

Opportunities for women were limited in the product distribution chain at the time. Women frequently worked in retail stores, low-paying employment viewed as temporary until marriage beckoned. Of course, too, the “factory girl” phenomenon emerged in the 19th century. These and other contemporary female occupational roles have been extensively studied. But salesmanship away from the retail environment, and drumming in particular, was generally a male preserve, with exceptions such as book agency and marketing insurance to females. Spears noted (see p. 145) that women drummers in the late 1800s did not exceed 1% of the total, and even by 1910 the percentage did not exceed 2%.

Probably due to the relatively small number of women who worked as drummers, they have received, at least by my canvass, little scholarly attention. But there were, at a minimum, hundreds of them in the United States in the 1880s through to World War I. They form a fascinating subset of the drummer corps, worthy of serious attention. In 1885 one still might find news articles dismissive of female attempts to travel on the road. The Weekly Calistogian of April 22, 1885 in “Women as Drummers”, enumerated a dubious list of reasons why women did not belong in this field. The journalist assumed a woman’s charms would be a major part of her success, and this would not work with the large married set of merchants and buyers. He also thought women could not handle the drinking that was characteristic of the male drummer, an aid to chumming with merchants, or carry his “irrepressible pertinacity and lordly assumption”.

But women drummers did emerge, due to persistence and independent thinking, and soon newspapers covered the phenomenon more responsibly and realistically. The women might sell any goods, from copperware to corsets, but often handled soap and cosmetics, clothing, food or beverages, and other goods associated with family life. Some had notable success, earning high salaries and commission but even an average female drummer could make $1000 annually, compared, said one report, to 80% of that for most store clerks (“Women on the Road”, Buffalo Evening News, July 27, 1903). Many women did even better, and some treasured the freedom and independence of the road.

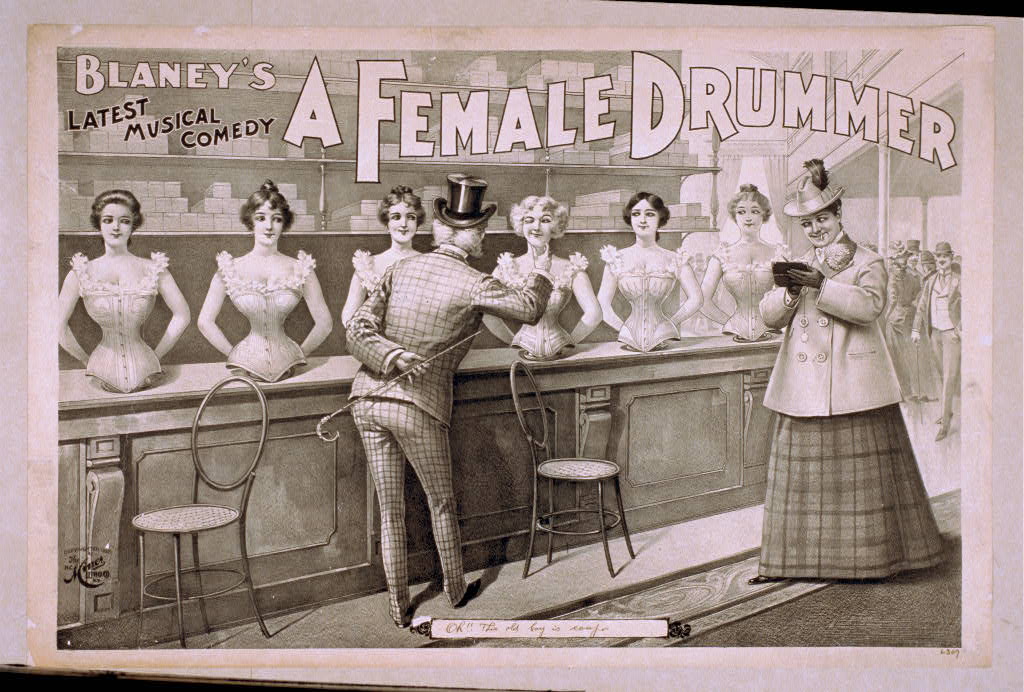

Female drummers were visible enough to form the subject of an 1898 comic stage musical, A Female Drummer, by Charles E. Blaney, which ran successfully in regional and urban theatres. This kind of attention cemented their status, along with the more numerous male corps, as period cultural symbols. Some news accounts considered the female drummer a manifestation of the New Woman creed then current, others disclaimed any such connection.

The popular media generally portrayed the women as conducting themselves respectably and being treated in similar fashion by merchants and male drummers. A (Canadian) account, in the Stanstead Journal, September 24, 1896 (originating in San Francisco), is typical, portraying a young “Miss Byrne” as all-business and able to give male drummers “pointers”, even as they presumed to teach her the ways of effective selling. The article can be read as an early reproval of mansplaining.

There is little hint in contemporary popular media of female drummers being subject to sexual harassment. But newspapers and magazines were mostly a “family” medium, not the kind of space where serious social problems were examined even if they were recognized as such, barring the occasional expose piece but this was not the usual fare of most newspapers. Male drummers were often referred to as “mashers”, but such behaviour was regarded as typical, even expected, hence not calling for special condemnation.

Thus, valuable as a press survey is in other respects, it might mislead on this point. Resort to works of fiction and memoir tells a deeper story. In numerous works of fiction ca. World War I the author Edna Ferber, a daughter of a small town dry-goods merchant, recounted the experiences of Emma McChesney, aka Mrs. McChesney. A mother and divorcee, she went on the road to notable success selling petticoats. In the 1913 Roast Beef, Medium: The Business Adventures of Emma McChesney, the protagonist recounts an attempted seduction by a handsome younger male drummer she meets in a small town hotel. She fends him off successfully, in part because he was married, and perhaps also in acquiescence to conventions of the day her readers would have regarded as mandatory.

A New York society figure and widow, Alice Foote MacDougall, became a successful coffee vendor and restaurateur (1910s-1930s), a career prompted by early widowhood and financial distress. In her 1930 memoir Alice Foote MacDougall: The Autobiography of a Business Woman, she describes a similar seduction attempt, this time by a country rogue who was driving her from a remote railroad station to her destination, a sanitarium she hoped would buy her line of coffee and cocoa. She fought him off with the handle of the buggy’s bull whip and a strong tone. She wrote:

“Then the gentleman stopped the horses, and pressed close to me and began to make love. His horrid breath heated my cheeks. I was conscious of his face coming closer and closer to mine. Disgust — there isn’t a word in the English language strong enough for what I felt. The whip was in the socket. I seized it. Words are often useless things, but the words I used, the whip held near the lash with the butt-end free, the look in my face, carried some idea to the beastly creature and he desisted. I did not get to the sanitarium nor have I ever tried to return. He turned his horses about and we drove back to the little town. Any woman can imagine my relief when I saw the train arrive to carry me back to wicked New York. Thus one business episode ended.

That was all it was, an episode of a business day. It did me no harm. I laughed over it the next day and for many months after would recite part of the poem, “The White Goblet and the Red,” that had been recited with so much fervor by my amorous companion.

This is the kind of thing that happens to women in business. This is the price one pays for emancipation —it is scarcely worth while, it seems to me. Perhaps because I am mid-Victorian”.

My survey of the female drummer phenomenon suggests no real pattern, by which I mean among the women themselves. On the issue of sexual harassment, Alice Foote MacDougall, an avowed Victorian who would have remained a housewife had she been able, seemed to regard instances as inevitable, and thus ineradicable. Edna Ferber, via the voice of Mrs. McChesney, by contrast evinced a more no-nonsense approach, invoking prevailing morality to dissuade mashers from their course, e.g., where married, or attempting to seduce the older women.

In Part VI of my recent blogpost series, “’The Ubiquitous, Irrepressible Drummer’”, I review two examples of the rare female whiskey drummer, able to penetrate the male sanctum of the saloon to sell their wares successfully. While both dressed soberly and maintained a business mien and style, one paid for drinks on the house and drank the wares with her customers, a practice most male whiskey drummers followed, while the other abjured this ritual. In the same Part VI, I discuss a case where a woman, contrary to the picture usually portrayed in the press, may have granted sexual favours to increase her income on the road. To what extent such practices occurred and were encouraged by their employers, in the specific context of commercial traveling, is a fecund subject for historians.

Finally, the spurs to enter drumming varied too, from early widowhood and consequent financial need to simple curiosity and wanderlust. The road provided a rare opportunity for a woman of limited means to escape the straitened course otherwise available including shop clerk, factory worker, nurse, or servant. The motives seemed more various than for males, who (most of them) ended married with a family to support, hence assuming the occupation for more conventional reasons.

Fabulously fascinating, Gary. Thanks for exploring this topic.

Thanks Jan, much appreciated, and all reading should take note of your site and the great resources there in consumerism, restaurant history and more.

Gary