All Cooped Up: Gender and Chicken Industry after the Second World War

Margaret Weber

Editor’s note: This week we highlight the dissertation research of recent History PhD Margaret Weber.

After the Second World War, the development of agribusiness exploded with unprecedented ferocity. Out of all of the changes that agribusinesses attempted to impress upon farming communities, a reorientation of gender roles may be the most profound. This was clearly evidenced by the postwar development of the chicken industry. The egg and chicken markets had long been the province of rural women. Just one of many of the diverse tasks these women took on, egg and chicken money play a key role in helping the farm stay afloat during tough times. By diversifying their income, chickens historically helped farm women put food on the table, engage in community trade, and even stave off a foreclosure.[1] It was also an important part of local exchange, balancing networks of labor between different farmsteads. Chickens, like dairy products and garden vegetables, helped create a “social security” for area farms. Diversification was a cushion against market downturns. And even as other farm commodities left the traditional female labor sphere (like dairy), chickens remained one of the central points of female farm labor long into the twentieth century.[2]

Noontime chores: feeding chickens on Negro tenant farm. Granville County, North Carolina. Dorothea Lange, photographer, July 1939, Farm Security Administration. Digital ID fsa 8b34187 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/fsa.8b34187

This was partly because of the nature of American eating habits and meat production. Whereas the pork and beef market industrialized in the Gilded Age, chickens resisted such efforts. To some extent, this was due to egg production. Many farmers who attempted to industrialize chickens focused on egg laying rather than meat-type production. As such, chicken as a meat source remained mostly limited to “spring” cockerels (young males slaughtered in their first year) and old hens that had outlived their egg laying capabilities. Chickens, therefore, were a luxury item rather than a food staple. It was not until the 1930s and 1940s that chickens moved away from female hands.[3] Like other commodities, once it became clear there was money to be made, rural men began to take over the field. In the end, the Second World War was the catalyst for the larger changes to the chicken industry. More and more Americans developed a taste for the white meat. Moreover, for the first time, technological advancements in breeding and processing caught up with the demand. Aware of the new market, firms quickly moved to vertically integrate the industry.

But just because there was money to be made did not mean that rural gender expectations immediately realigned themselves to fit these new developments. Out of all of the farm commodities, the chicken industry was most boisterous in its own defense of the trade’s masculinity. After all, how do you get men to buy into an occupation that was once the realm of their mothers and sisters? How do you make the chicken coop as respectable as the field or barn? The key was to separate current masculine chicken labor from the feminine handling of chickens in the past.

Handling crate of chickens at cooperative poultry house. Brownwood, Texas. Russell Lee, photographer, July 1939. Farm Security Administration. Digital ID fsa 8b23453 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/fsa.8b23453

This strategy naturally fit into agribusinesses’ temporal recreation of the past, present, and future. In the past, women handled chickens. This was because the business was small, inferior, and largely inefficient. But now, with the natural advancement of time (in terms of technological-determinism), the industry had taken steps to progress. It was men, with their natural inclination towards science and business, who moved the industry from the neighbor’s backyard to a million dollar industry. Even the broiler industry’s own lore both established a female presence, yet quickly diminished it to a mere placeholder, a token of the past. According to industry sponsors in Delmarva (one of America’s poultry capitals), the first person to enter into modern chicken farming was a Mrs. Wilmer Steele of Ocean View, Delaware. Steele, never actually referred to by her given name of Claire, accidently ordered five hundred young broilers in 1923, unintentionally starting the region’s broiler industry.

Steele’s story was well trod ground for Delmarva’s poultry companies and their allies. It played a critical role in helping to juxtapose the past’s “feminine” chicken labor from the modern masculine occupation they claimed by the forties and fifties. Industrial histories, from company speeches to festivals pamphlets, all emphasized that Steele’s story was simply a lucky trick of history, a completely unintentional action.[4] This contrasted neatly with the cultivated image of the current industry. Companies and trade groups, controlled by men, claimed a purposeful movement towards improvement, a deliberate and scientific quest for a better bird. Referencing the famous “Chicken Of Tomorrow” contest of 1948, Paul Philips admired how far Delmarva’s chicken production had come, “We now have the rapid maturing, highly efficient, well-meated, and white-feathered crosses that far out-perform even the greatest expectations of a few years ago.”[5] And the march toward progress was fundamentally a masculine endeavor, often driven by competition between men. Edmund H. Fallon, general manager of the Grange League Federation, presented such an argument during the 56th annual convention of American Feed Manufacturers in 1964. He claimed that real competition did not take place between companies or products, but rather, “between men who direct, manage, and operate the businesses.”[6] The only successful companies then were those that employed men who frequently sought improvement. Those, both businesses and men, who were not willing to continually grow were doomed to fail.[7] Fallon very well may have been foreshadowing his own company’s future, as little more than a month later the GLF merged with two others, eventually emerging as the farm retailer Agway.[8]

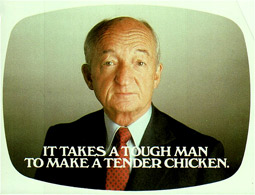

Another key to affirming the masculinity of “chicken men” was to emphasize the role of science and technology within the industry, from the broiler house to the butcher’s block. Agribusinesses across the board often invoked conceptions of scientific development to sell their ideology. But for those involved in the poultry business, science became a tool to again denigrate out past female labor while also adding to a sense of masculine professionalization and expertise. The recurring Delmarva Chicken Festival held several gender-specific events. The fair relegated women to the Miss Delmarva Queen contest or cooking contest, while male scientists, dealers, and businessmen dealt with promotion and research development.[9] Perdue Chicken was especially quick to point out its scientific prowess to farmers and consumers alike. In its advertisements to New York City housewives, Perdue claimed its pampered chicks were “scientifically grown” for the best quality.[10] Another company letter to meat markets claimed that Perdue had the “most extensive research program constantly improving our quality.”[11]

http://adage.com/article/agency-viewpoint/frank-perdue-a-tough-man-choose-agency/229067/

Perdue exploited these ideals to sell their contract farming as a masculine, ultimately self-sufficient profession. One radio commercial asked interested farmers, “if the idea of being able to spend more time at home and being your own boss sounds interesting.”[12] In a TV commercial, Frank Perdue insisted that with a few acres and a few hours, men could easily own their own broiler house.[13] All of Perdue’s advertisements underscored the masculine traits of contract farming, a production system that seemed to subvert its gendered expectations. Other companies also stressed the ability of rural men to provide for their families through chicken farming. When seed houses like Pioneer and DeKalb entered the chicken market, they specifically highlighted how farmers could continue to earn a good living and brighten their farm’s future all at the same time. Pioneer’s Hy-Liner “Expand” pamphlet perhaps put it the most bluntly of all, outright stating their unit was not “a pin money operation,” a jab often used to devalue female work[14] This, of course, was a deliberate declaration of masculine prowess, a fundamental disconnection between women’s and men’s labor. Male labor was about providing on a large scale for his family. Conversely, it argued that women had used chickens to supplement inessential consumption. It was this deliberate separation of the past and present, profit margins, and gendered labor that proved to be a critical theme for agribusiness involved in poultry.

These tactics of separation were not just about changing the dynamics of chicken farming’s gendered expectations, but also emphasizing how farmers could continue to be men in an increasingly hostile and depressed farm market. The price squeeze of the postwar period put a new strain on this Jeffersonian ideal in rural America. Companies emphasized that success only came from men with determination, efficiency, and a will to adapt to a changing economy. Pioneer argued that while their poultry production units would not save a marginal farm, they could “offer a good farmer an opportunity to keep pace with the rest of the economy.”[15] Frank Perdue maintained that many poultry producers’ refusal to take risks or overall poor management led them to failure.[16] Men who lost their farm consequently did so because they lacked these inherent masculine traits. It was a view shared not just between agribusinesses but academics and trade groups as well. John A. Hopkins, a professor of Agricultural Economics and author whose work Frank Perdue used as research for his speeches, argued that modern farmers must now operate in in the larger capital economy and that poor management would be punished severely. The president of the Delmarva Poultry Industry, A.E. Bailey, remarked that broilers are, “a fast moving business and demands changes and anyone who refuses to change with it will be out of business or broke.”

Of course, the fundamental point of this stance was that by joining Perdue’s contract team, buying Hy-Line equipment, or adopting other forms of modernization, a stressed farm and its steward could join the fast track to success. Pioneer noted that their chicken units did not require extra land or labor to increase profits.[17] Frank Perdue claimed that his company’s experience and oversight made it easier for his farmers to succeed. In fact, it was Perdue’s own contract hatching program that enabled, “more of our good farmers to remain on the farm.”[18] The connection between success, consumption, and masculinity was a key element in the ultimate goal of agribusinesses: to make themselves absolutely indispensable to postwar agriculture. By introducing new standards of masculinity, poultry agribusinesses redesigned a cultural landscape to better fit their own desires. Such corporations then held the key to retaining masculinity itself, through consumption of their necessary products and expertise.

This restructuring echoed one of the most important goals of corporate agriculture, to shift dependence from local exchanges networks (neighbors, community, and of course, wives and children) to corporate institutions: their products, their employees, and their expertise. By imposing a simplified expectation of middle class, gendered spheres, companies deprived exchange communities of their most necessary component, women. Key links that not only connected farm communities’ together, farm women also provided much of the basic labor, knowledge, and provisions to keep a farm functional. But gendered spheres culled these important roles, eliminating women from local positions that empowered them and ultimately led to a breakdown in community exchanges.

[1] Lu Ann Jones, Mama Learned Us to Work: Farm Women in the New South (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2nd edition 2002), 1-49.

[2] Dorothy Schwieder and Deborah Fink. “U.S. Prairie and Plains Women in the 1920s: A Comparison of Women, Family, and Environment.” Agricultural History 73, no. 2 (1999): 183-200.

[3] Horowitz, Putting Meat On the American Table, 103-110.

[4] Delmarva Poultry Industry (hereafter known as DPI), “Memo to DPI Speaker Bureau: Delmarva Poultry Industry: History of the Chicken Industry,” February 15, 1964, Box 33, File 339, Perdue Chicken Records; “Onancock Delmarva Chicken Festival Program,” 1955, Box 1, File 8, Delmarva Poultry Industry Records.

[5] DPI, “Memo to DPI Speaker Bureau: Delmarva Poultry Industry: History of the Chicken Industry,” February 15, 1964, Box 33, File 339, Perdue Chicken Records.

[6] Edmund H. Fallon, “Modern Management for Agri-business firms,” May 13, 1964, Box 33, File 335, Perdue Chicken Records.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Jay Pederson, International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 21 (New York: St. James Press, 1998), 17-19.

[9] Dover Delmarva Festival Pamphlet, 1950, Box 1, File 3, Delmarva Poultry Industry Records.

[10] Wildrick & Miller, Inc., “Radio Commercial #4,” 1967, Box 29, File 293, Perdue Chicken Records.

[11] Letter from Frank Perdue to New York City retailers, January 8, 1971, Box 29, File 293, Perdue Chicken Records.

[12] Wildrick & Miller, Inc. “Radio Commercial: Breeding Hens,” 1969-1971, Box 29, File 299, Perdue Chicken Records.

[13] Wildrick & Miller, Inc. “TV Commercial: Chicken Raising,” September 1, 1971, Box 29, File 299, Perdue Chicken Records.

[14] Pioneer, “Expand Pamphlet” The Hy-Liner (1964), Box 10, File 6, Pioneer Eastern Division Records.

[15] Pioneer, “Pamphlet to potential customers,” The Hy-Liner (July, 1964), Box 10, File 6, Pioneer Eastern Division Records.

[16] Frank Perdue, “Bankers Speech,” 1964, Box 33, File 338, Perdue Chicken Records.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Frank Perdue, “Bankers Speech,” 1964, Box 33, File 338, Perdue Chicken Records.

Great work, Dr. Maggie!

Amazing read! I have never thought about the gender dynamics inherent in the restructuring of the agricultural business.