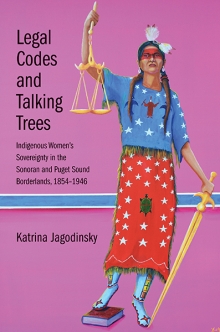

Legal Codes & Talking Trees

Katrina Jagodinsky, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

In a few months, members of the Rural Women’s Studies Association will gather in Ohio to discuss “Surviving & Thriving: Gender, Justice, Power, and Place-Making.” Such concerns are fundamental to the histories of six women featured in Legal Codes & Talking Trees: Indigenous Women’s Sovereignty in the Sonoran and Puget Sound Borderlands, 1854-1946 (Lamar Series in Western History: Yale University Press, 2016). In telling the remarkable stories of Akimel O’odham, Duwamish, Salish, Sauk-Suiattle, Yaqui, and Yavapai women and their communities, understanding the legal regimes they navigated proved important, of course, but no more so than comprehending the places and the people they knew, they loved, they might have hated. The book considers Native women’s efforts to invoke state protections against sexual violence, to retain custody of their children in an era of Indian abuses, to inherit property from white fathers, and to retain lands stolen through belligerent and bureaucratic violence. Through their gendered articulations of justice and power, each of these women challenged the legal violence of settler-colonial place-making in an era of dispossession, and rural communities continue to grapple with the legacies of these challenges in their efforts to not only survive, but thrive in the twenty-first century.

In a few months, members of the Rural Women’s Studies Association will gather in Ohio to discuss “Surviving & Thriving: Gender, Justice, Power, and Place-Making.” Such concerns are fundamental to the histories of six women featured in Legal Codes & Talking Trees: Indigenous Women’s Sovereignty in the Sonoran and Puget Sound Borderlands, 1854-1946 (Lamar Series in Western History: Yale University Press, 2016). In telling the remarkable stories of Akimel O’odham, Duwamish, Salish, Sauk-Suiattle, Yaqui, and Yavapai women and their communities, understanding the legal regimes they navigated proved important, of course, but no more so than comprehending the places and the people they knew, they loved, they might have hated. The book considers Native women’s efforts to invoke state protections against sexual violence, to retain custody of their children in an era of Indian abuses, to inherit property from white fathers, and to retain lands stolen through belligerent and bureaucratic violence. Through their gendered articulations of justice and power, each of these women challenged the legal violence of settler-colonial place-making in an era of dispossession, and rural communities continue to grapple with the legacies of these challenges in their efforts to not only survive, but thrive in the twenty-first century.

Prescott, Arizona has a bloody past and a racially-fraught present. It is located in the aboriginal territory of the Yavapai, a stunning, transitional landscape on the northern fringes of the Sonoran Desert buffered from Spanish and American intrusions by the scarcity of water and the tenacity of tribal neighbors who fended off outsiders for generations. The U.S.-Mexican War made Yavapai lands part of New Mexico in 1854, and the discovery of gold nearly a decade later made Yavapai people and their lands vulnerable for American expansionists. Dinah Foote was born into the era of forced marches that the American military had practiced in the Southeast in the 1830s and perfected in the Southwest in the 1860s and 1870s. After being forcibly removed to the San Carlos Apache reserve, already home to a people with a different language group, Yavapai families like Dinah’s were forced to send their children to the Santa Fe Indian School. Dinah struggled in Santa Fe, and the superintendent complained about her “moral influence” on other girls, but she remained confined there until 1900, when she turned eighteen and returned to San Carlos. By then, Dinah’s relatives had made an unsanctioned return to their Prescott homelands that officials loosely tolerated because of declining conditions at San Carlos and an increased demand for cheap laborers in the Prescott vicinity. Dinah married Robin Hood, a Yavapai veteran of the Arizona Indian Wars, when she joined her family camped on the outskirts of Prescott and worked with her relatives and neighbors to reconstitute Yavapai life as they knew it at the onset of the twentieth century.

Known to us primarily because of a 1913 murder in the Yavapai camp that Prescott journalists sensationalized and Supreme Court jurists debated in Arizona’s first year of statehood, Dinah Foote Hood’s family participated in the continued Yavapai resistance against dispossession and violence at the hands of their American Prescott neighbors. Subject to sexual violence, physical assault, and daily degradation, Dinah Hood and her relatives nonetheless remained on Yavapai lands until tribal leaders—including renowned Yavapai basket-maker Viola Jimulla and prominent Prescott citizens—secured federal recognition of their lands in 1935 and established a postage-stamp sized reserve that included the camp Dinah’s family claimed when they escaped San Carlos.

Federal, state, and local archives tell this story from a distance. Archival records from the turn of the twentieth century rarely name particular Yavapais, often misidentify them in photographic and manuscript accounts as Apaches, and depict them as ephemeral in addition to anonymous Indians. What they obscure is the intimate proximity of Dinah Foote Hood and her Yavapai relatives to the Prescott community. For a more accurate view of the daily engagement between Yavapais and Americans in this small town that was at one time Arizona’s territorial capital, you have to walk along Granite Creek, a rare perennial stream that flows between the Yavapai County Courthouse at the center of Prescott’s historic downtown plaza and the Sharlot Hall Museum, Library, and Archives named for Arizona’s first territorial historian. This tributary of the Verde River also flows past Fort Whipple, erected in 1864, and now maintained as a hospital and administrative grounds for the Veteran’s Administration. Between these sites of military and judicial power lies the Yavapai Prescott Indian Tribe’s reservation, itself a representation of the power of rural Indigenous women’s strenght and leadership. My opportunity to walk this creek bed and its surrounding banks came through an invitation from Linda Ogo, Director of the YPIT Cultural Research Department, and tribal archaeologist Scott Kwiatkowski.

As we talked and walked along an active archaeological site, Ogo and Kwiatkowski explained what the archives had not about the return of Dinah Hood’s family to their homeland. In the decades following the 1875 Yavapai removal, Americans expanded Prescott’s municipal infrastructure and used the Granite Creek banks between the Fort and the Courthouse as a dumping ground for their trash. Yavapais returning from San Carlos and elsewhere occupied this jurisdictional wasteland unoccupied and disregarded by Prescott residents. Women like Dinah Hood used glass shards from trash heaps as scraping tools for crafting and recycled discarded tin and cardboard to construct their homes. They also walked to the town plaza less than a mile from their camp to sell baskets and firewood while their sons, husbands, and fathers worked for neighboring ranchers and farmers, labored in the railyard or lumber mill, and picked up odd jobs at the Fort that overshadowed their camp.

Records and recollections indicate that Yavapais found some allies and advocates among their Prescott neighbors, but they also found plenty of others quick to demean and abuse them. Despite their close comings and goings, despite sharing conflicts and contracts, Prescott residents for the most part failed to know the Yavapais who lived amongst them as neighbors or as friends, and except when they were immediately useful, considered them as novelties. Born in 1882, Dinah Hood survived personal and collective abuses as she persisted in raising children who served in the U.S. military, who served in tribal office, and who served each other at family reunions in later generations. Dinah’s children became American citizens in 1924, supported the WWII Yavapai veterans who pushed Arizona to allow Native people to vote in 1948, and have helped to build tribal communities with growing economies, strengthening cultural practices, and increasingly powerful political influence.

Today, the Yavapai Prescott Indian Tribe is one of the largest employers in a town that, like many rural communities, is seeking ways to sustain itself into the twenty-first century. Place-making is a significant part of these rural efforts to thrive. The descendants of those who survived and committed nineteenth-century atrocities share the same grocery stores, the same playgrounds, and the same cafes, but they do not share the same histories. Collective efforts have been made and are underway to establish common ground in the past and present, but there remains in Prescott, as in much of the United States, a palpable divide in historical interpretation that rural women concerned with gender, justice, and power frequently occupy. Like Dinah Hood did a century ago, Yavapais today are reaching out to non-Indians in their homelands for financial opportunity with a firm understanding of the contentious histories between them. In order to transition from surviving to thriving, rural communities like Prescott need to consider the historical and contemporary implications of gender, justice, and power in their place-making. Incorporating and perhaps even emphasizing Yavapai histories of surviving and thriving as a fundamental component of Prescott’s past and present would be an ideal place to start.

Rural women’s studies scholars are uniquely positioned to serve the communities we write about in facing and acknowledging our painful pasts head on. In focusing its attention on women like Dinah Hood, Legal Codes & Talking Trees takes up these troubling histories in an effort to highlight the sophisticated strategies of Indigenous women to make legal and moral claims on their communities of Indians and non-Indians alike. Those claims continue to be pressed, of course, and they should be celebrated rather than suppressed or diminished. Remaking the heroes of our rural communities will take time and cause occasional discomfort, but historians have much to contribute in this campaign and rural women’s stories may be at its heart. As tribes throughout the United States become more invested in neighboring rural community’s economic development, sometimes encountering hostility from non-Indian residents as they do so, confronting the past to secure the future becomes all the more essential. Unraveling rural women’s entanglement in the settler-colonial project requires looking in on our own family histories of dispossession and conquest where we ought to acknowledge and address historical wrongs, but we might also find histories of alliances and advocacy that can pave the path toward the future. Dinah Hood relied on Yavapai friends and family to sustain herself in a hostile homeland, but her contemporary Viola Jimulla regularly reached out to non-Indian officials and allies to leverage Yavapai interests into political and economic authority. Today’s Yavapai Prescott Indian Tribal Board of Directors likewise reach across hostile histories to forge fruitful partnerships as they work to ensure their community will thrive into the twenty-first century and beyond. Making stories like Dinah Hood’s more widely known through works like Legal Codes & Talking Trees is hopefully helpful in turning histories of surviving into thriving futures as our rural communities engage in place-making with gender, justice, and power firmly in mind.

Legal Codes & Talking Trees: Indigenous Women’s Sovereignty in the Sonoran and Puget Sound Borderlands, 1854-1946 won the Coalition for Western Women’s History’s Armitage-Jameson Prize–awarded annually “for the most outstanding monograph or edited volume published in western women’s, gender, and sexuality history,” and received an Honorable Mention for the Frances Richardson Keller-Sierra Prize from the Western Association of Women Historians.