Megan Birk, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

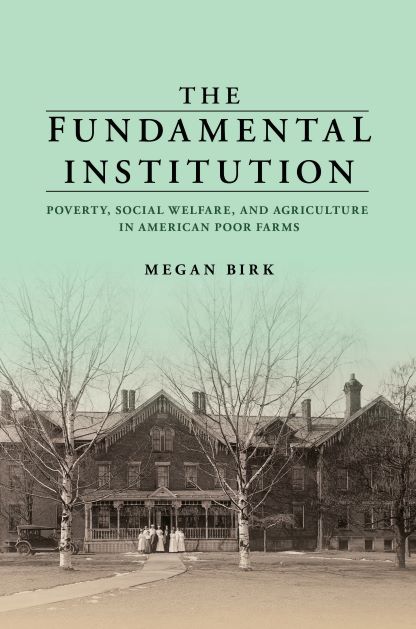

In my recent book The Fundamental Institution: Poverty, Social Welfare, and Agriculture in American Poor Farms, I discuss all the disparate groups of people that poor farms served – the young and old, the sick, the homeless, the disabled, the abandoned… It’s a long list. In thinking and writing about the people who lived at and used poor farms, I also spent a lot of time considering the lives of employees. Many of them lived on site, with their own families, to work as both farm tenants of sorts and institutional managers. Edna White was one such woman, working as both matron alongside her husband, and then as the first female superintendent in California after his death. She raised her own two children at the county hospital (California’s term for poor farm), took care of between twenty and forty residents, and managed a staff that included a farm laborer, nurses, and sometimes a cook. She cared for residents isolated on the farm during the flu pandemic of 1918, and dealt with criticism from state officials who complained about structural issues with the building; problems they laid on her doorstep despite certainly knowing she could not enact repairs without county approval. In 1930 White suffered a different type of indignity, when the census enumerator listed the man who worked the farm as the “head of household” despite her position as superintendent and matron.

Women were critical parts of the poor farm staff. Poor farms were one of the only options for single mothers, married women, and teenage girls to earn cash wages in rural places. They sewed, cooked, nursed, and cleaned. Typically they were managed by a matron – the wife of the superintendent – who worked in a hybrid space. She lived in a large building but did not own the furnishings or the house; she cooked and nursed and cleaned for both residents and her own family alike; she earned wages and had her work evaluated by county officials and the public in a way that most women did not; she ran a household staff while doing work considered by some to be undesirable and low-class; her children lived on a farm but were also surrounded by people who might have an addiction, an illness, or an emotional disability; she was both a farm wife and a working woman. In today’s terminology she multitasked: everyday, all day, often for many years. As might be expected not all matrons rose to the challenge and did so with skill or kindness, but many did just that. Counties lauded them for being “industrious and large-hearted” and critiqued them for their failings: “There seems to be a lack of motherly kindness and humanity in her methods.“ Couched in terms of 19th century gender norms these women received scrutiny not just for rural homemaking but as wage workers.

As the difficult years of pandemic life continue to unfurl, I’ve watched as colleagues and friends in academia and other positions face dilemmas that had a familiar historical ring – women were both working for wages in less-than-ideal conditions while also tending to and worrying about the health and safety of their own families. The pandemic took the challenges of working motherhood and amplified them all. It turned many of us back into caregivers for sick or elderly family. Faculty friends and colleagues worked at night after children went to bed, they woke earlier to try and accomplish yesterday’s unfinished tasks, they strategized about how to keep their families safe in spaces that were unyielding in their seeming dangers. Recently many of us have lacked the help of our usual social networks and were pushed away from academic productivity (and in some cases out of wage earning altogether) and toward aspects of caregiving many never envisioned for themselves. As a childless woman, I watched sort of helplessly as people tried to tread the water of a pandemic in a country that values neither motherhood nor the intellectual and economic contributions of women as workers. While everyone lifts their own burdens, some were decidedly heavier than others.

While writing about matrons, I often found myself wondering how these women did it, the grind of work weeks that typically meant 80-100 hours of labor. During the pandemic it’s reminded me of our present, because I don’t know how many working mothers and women have been doing it either. Matrons who did wage work because their husband’s career demanded of them more than housewifery were outliers among their peers whose occupation was simply farm wife, because their efforts brought them in to constant contact with different and ever-changing institutional circumstances while on a farm and in their home. American women today are outliers among peers, not only because of our rapidly diminishing bodily autonomy, but because there are few social supports or financial aids to help with parenthood, and in academia the necessity of living away from family only makes that problem worse.

The cost for women employed as matrons was sometimes their health and that of their children – matrons nursed residents as typhoid, TB, and other diseases ripped through their institutions, and some of their bodies broke and aged early from the strain of the physical work. At what cost for our current moment’s multitasking women remains to be seen, but what has no doubt been slowed is the intellectual contributions of our peers and colleagues asked to keep too many tasks balanced on a faulty foundation of “business in academia as usual,” without COVID-safe and affordable daycare, without vaccines for children under 5, without provisions for the care of our elders, without healthcare unattached to a specific job, without reasonable and paid parental leave. We study the past to see progress over time and make comparisons. We talk about the strains of rural women’s lives in past tense: being isolated during a long winter on a farm, kneading bread while nursing a baby, or darning socks while rocking a cradle with a spare foot, but recently women have experienced social isolation of their own, staying home to avoid the transmission of COVID while being separated from the support of family and friends, baking bread to both pass the time and to cope with interrupted supply lines, trying to write late at night while the children sleep. It’s different, but it’s also strikingly similar. There are no perfect parallels here, just the nagging reminder that competency is often rewarded with more work, leading women to carry a larger service burden both at home and in the workplace.