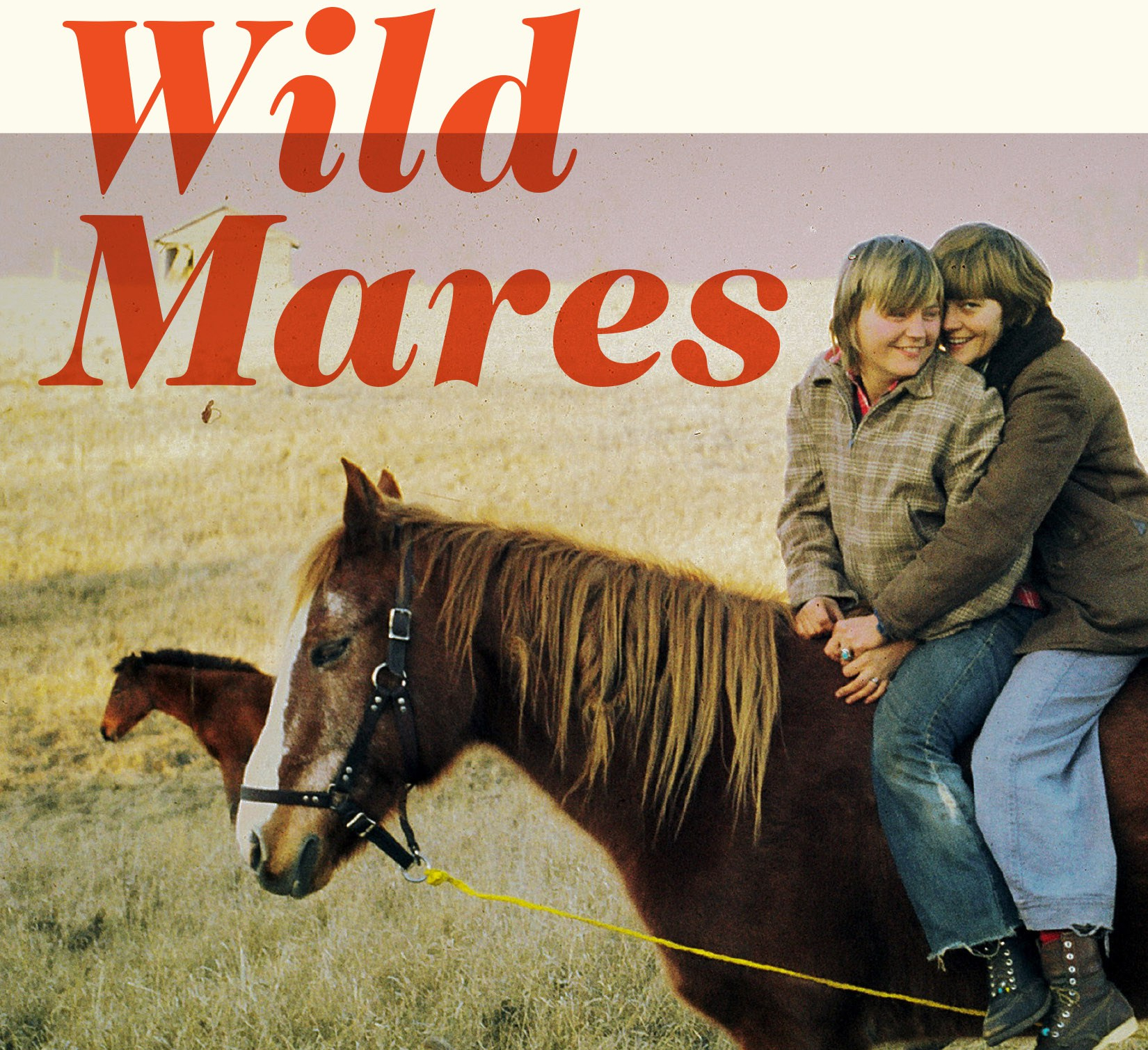

Rising Moon

by Dianna Hunter

“Rising Moon” appears here with edits by the author from Wild Mares: My Lesbian Back-to-the-Land Life by Dianna Hunter (University of Minnesota Press, 2018). Copyright 2018 by Dianna Hunter.

My memoir, Wild Mares, chronicles my journey through six lesbian-feminist land projects during the 1970s and ‘80s. In 1974, my friend Shirley, her daughter, and I arrived at Rising Moon near Aitkin, Minnesota, after riding our horses 240 miles from Haidiya Farm in Wisconsin. Our first night at Rising Moon, Shirley, Sara, and I bedded down on bunks that Lisyli and some of the others had built in a shed after their house burned. Leftover heat from the day lingered in the shed, and while laying out my bedding I noticed that the windows were screened. I decided to open the inner sashes so that we could catch a breeze. I fell asleep fast but soon woke to the stinging bites of mosquitoes. I pulled the sleeping bag over my head to fend them off, and as I tried to fall asleep again, I told myself I should have known that the walls and siding of the old shed must be riddled with chinks and cracks. I lay awake, listening to the mosquitoes droning as they searched for openings in the covers. The sound itself was torture and seemed to increase the itching of my earlier bites, but I could only stand the heat so long before I had to unzip the sleeping bag and lay myself open to a new attack. I swatted until I was so tired that I had to cover myself, and I repeated the routine through the night. In the morning I didn’t exactly wake but just sort of rolled out of my bunk and staggered outside.

My memoir, Wild Mares, chronicles my journey through six lesbian-feminist land projects during the 1970s and ‘80s. In 1974, my friend Shirley, her daughter, and I arrived at Rising Moon near Aitkin, Minnesota, after riding our horses 240 miles from Haidiya Farm in Wisconsin. Our first night at Rising Moon, Shirley, Sara, and I bedded down on bunks that Lisyli and some of the others had built in a shed after their house burned. Leftover heat from the day lingered in the shed, and while laying out my bedding I noticed that the windows were screened. I decided to open the inner sashes so that we could catch a breeze. I fell asleep fast but soon woke to the stinging bites of mosquitoes. I pulled the sleeping bag over my head to fend them off, and as I tried to fall asleep again, I told myself I should have known that the walls and siding of the old shed must be riddled with chinks and cracks. I lay awake, listening to the mosquitoes droning as they searched for openings in the covers. The sound itself was torture and seemed to increase the itching of my earlier bites, but I could only stand the heat so long before I had to unzip the sleeping bag and lay myself open to a new attack. I swatted until I was so tired that I had to cover myself, and I repeated the routine through the night. In the morning I didn’t exactly wake but just sort of rolled out of my bunk and staggered outside.

I’m sure I wasn’t at my best around the breakfast fire where the residents of Rising Moon gathered that first morning. We met a woman named Sierra and her dog, Gorgon, whom she’d adopted from the streets of Chicago. Ancient Greeks depicted the Gorgons as female guardians with snakes for hair and gazes that turned men to stone. In 1974, I had nearly given up on men because they showed so little interest in taking responsibility for male privilege and sexism, but Gorgon seemed like an unfair moniker to hang on any dog, especially one whose life on the streets had left her avoiding eye contact and touch.

Besides Sierra and Gorgon, we shared the breakfast fire with Otter, Maya, Lisyli, Selenekore, and four dogs. I hoped that we could get along and together give the slip to the whole patriarchal, militarized, racist, sexist, and materialistic society. I was prepared to do everything with women—to shop at women’s stores, to read women’s books, to eat food raised and prepared by women, to love women and raise children with women, and one day to hand off women’s institutions like our collective farms to younger women. I knew we had a lot of work to do first.

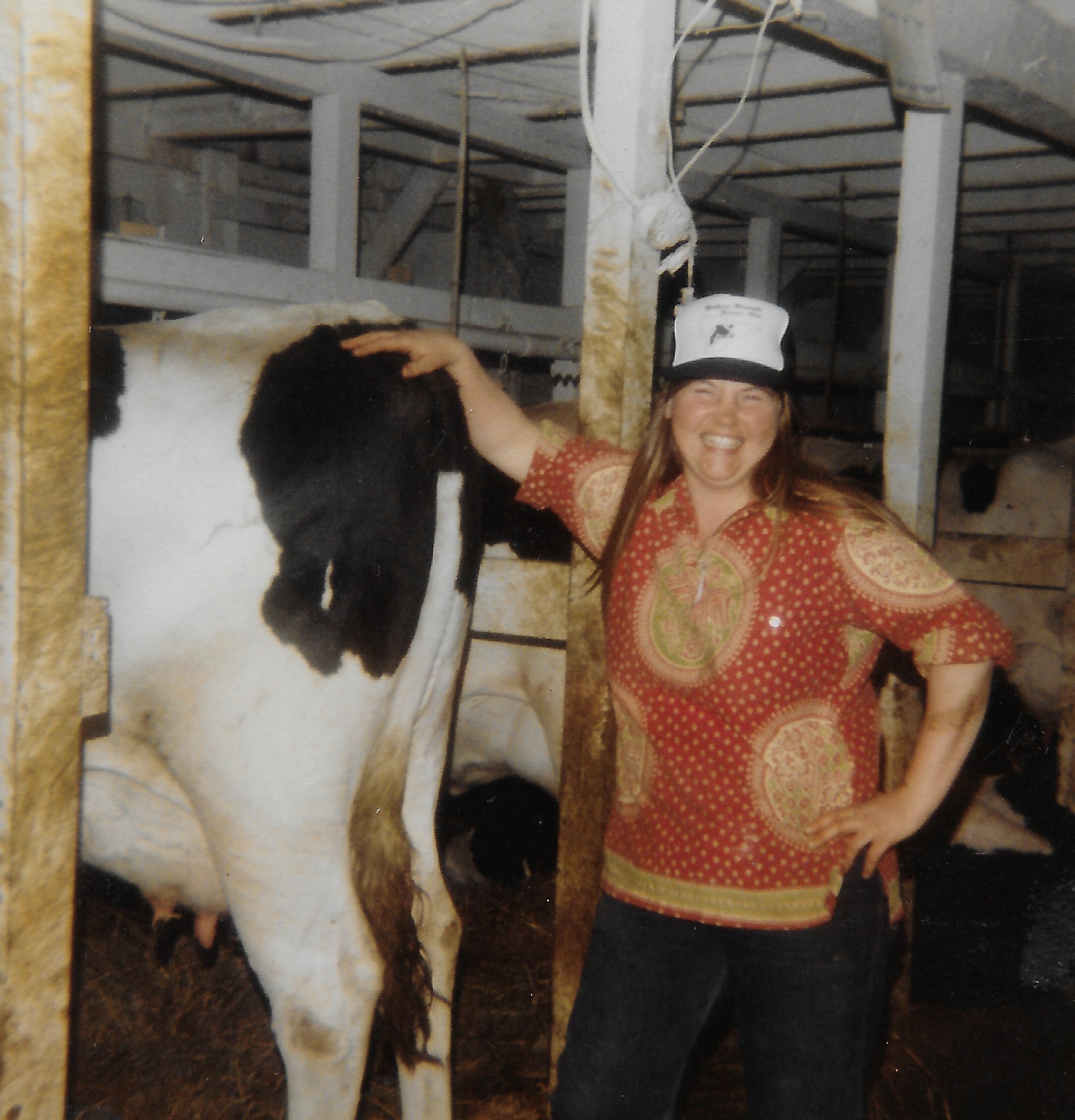

Dianna in the dairy barn at Happy Hoofer Farm. Photo by Ellen Wold.

At Haidiya Farm, we had lived without electricity and indoor plumbing, but the conditions at Rising Moon ratcheted up the difficulty. Our friend Kathy McConnell called it “subsistence” the next September, when she wrote her reflection on Rising Moon for the Twin Cities women’s paper Gold Flower. We did without a house, barn, fences, phone, furnace, electricity, power tools, and even some of the hand tools we needed. We borrowed them or improvised until we could afford them. We cooked over open fires, pumped water by hand, and staked our horses with ropes so they grazed the pastures in large circles, close enough to nicker back and forth, but far enough apart that they couldn’t get tangled.

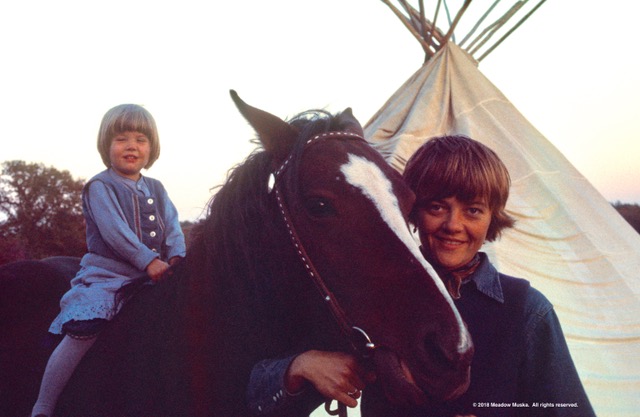

Shirley set up her tipi in a meadow downhill from the summer kitchen. I remember helping her stand up a frame of tamarack poles that she had tied together about three feet from their tops. As we spread the bottoms apart at the base, the poles fanned out and made a cone with a twenty-foot diameter. Once the frame was in place, we unfolded the cream-colored canvas she had sewn and waterproofed. She arranged it on the ground around the base of the poles and tied the folded top to a pole she had saved for lifting. Then she hoisted the canvas and unfurled it. Once standing, her tipi made me think of the Sydney Opera House or, when the fire was lit inside, a gigantic Japanese lantern. It was a majestic, graceful, magical thing to encounter in a Minnesota meadow.

Caption: Shirley, Sara, and Cheyenne at Rising Moon Photo copyright Meadow Muska 2018. All rights reserved.

Lots of back-to-the-landers were experimenting with tipis at the time because they made inexpensive homes that were more time-tested and durable than tents. We knew we were borrowing a design perfected by indigenous, nomadic people like the Lakota and Dakota who migrated across my native state of North Dakota before the European trappers and settlers displaced them. I wasn’t familiar with the concept of cultural appropriation yet, but even then I knew that we needed to remember whose shoulders we stood on and what the native people’s dispossession from their land and ways of life had cost them. I thought that we needed to do more than remember, too. When disagreements over treaty rights, harvesting rights, and human rights flared, as they regularly did, we needed to speak and act as allies.

Soon after Shirley put up her tipi, my lover, Molly brought her tipi canvas from Minneapolis, and we set it up on cedar poles in a meadow that felt private, separated from the main camp by a patch of wild blackberries and pussy willows. That night, we made a fire and experimented with setting the smoke flap, a part of the canvas covering that was left tied by one corner to the lifting pole so that it could be adjusted to catch a breeze and channel smoke. While the fire died, we fit ourselves together under my mosquito netting as we had done so many times in different beds, and I lobbied her to come and live with me. She said she still wasn’t sure.

The Ripple River valley curved around the feet of Rising Moon’s hills. Its switchbacks, sloughs, and wetlands made a vast nursery for mosquito larvae, but they weren’t the only bugs that plagued us. We were constantly checking for ticks, and during the day we swatted biting flies. We could usually thwart them by staying in the shade or, on a breezy day, on open, high ground. Our old hayfields had gone feral but still contained red and white clover, brome, timothy, and other domestic and wild grasses that gave us plenty of pasture for our horses and goats. We had trees for shade and firewood—oak, poplar, birch, and pine mostly, with tamarack and spruce in the lowlands.

To many onlookers, our lesbian-feminist back-to-the-land dream must have seemed strange and unrealistic, but we were far from the only ones who dreamed it. A decade later in her book Lesbian Land, Joyce Cheney anthologized more than two dozen stories from women involved in lesbian land projects in the United States, Canada, and Europe.

One woman who responded to Cheney’s request for writing, Buckwheat Turner, describes the impulse behind A Woman’s Place, in Athol, New York, in a way that strikes home for me. “Our original dream,” she says, “was a women’s utopia. We had a sense of wanting to move actively toward something rather than simply continuing to react to what society had designed for our consumption.” At the women’s farms where I lived, we were moving toward something, too, even though we never quite articulated our shared philosophies or goals.

Neither Shirley nor I can remember attending any meetings at Rising Moon, or participating in any organized discussions in which we made collective decisions about rules or plans. We talked around the fire circle daily and hashed out possibilities and ideas for what to do next. We reached decisions by consensus, with an ethic that, as I saw it, involved allowing everyone the most flexibility possible. No one took notes, and as far as I know no written records of our work exist besides this book and that retrospective that Kathy McConnell wrote. When a friend shared a copy of her article with me decades later, lost memories of particular jobs and projects came flooding back.

Haying at Happy Hoofer Farm. Photo by Dianna Hunter.

She describes breaking ground for the Rising Moon garden by hand, painstakingly turning the sod with a shovel and a drum. She remembers one person digging while another beat a rhythm that somehow made the work easier. She writes of the toll our “simple” lifestyle took:

Someone has read that living at a survival level this way takes three times more energy than living a “normal” gas, electricity, bathtub, four walls and a roof type life. Pump the water, haul the water, chop wood to heat it, then take a bath. Equal amounts of energy were spent initiating many Rising Moon visitors to the skills of the lifestyle.

Oh, yes, I’d almost forgotten about the visitors. Word spread about Rising Moon, and women came from many places to camp with us and see what we had going on.

An astrologer from Minneapolis visited that summer, and conversation turned to the Age of Aquarius, the spiritual awakening that many of us thought must be just about to dawn, ushered in at least partly by work like ours on the land. As I recall, the astrologer told us she had just returned from a gathering of colleagues, and most of them agreed that an age of love and understanding did indeed lie ahead, but she said we would first have to live through decades of fundamentalism and war. Her scenario seemed impossible. When the rest of us talked afterward, we didn’t see how such a setback could occur. I can see now that we vastly underestimated the reactionary power of fear and misinformation.

Dianna driving her gelding Dick with her adopted dog Eagle (formerly named Gorgon). Photo copyright Meadow Muska 2018. All rights reserved.

Meanwhile, word about Rising Moon got around our Aitkin neighborhood, and some of our neighbors decided to check us out. A few came to shop at our food co-op, which Jane and the others had already started by the time Shirley and I arrived. Our inventory consisted of pinto beans and brown rice in two galvanized trashcans, plus a gallon of tamari sauce. We bought our bulk food from the new-wave co-op in Minneapolis that Linda’s husband had helped start in 1971, and that Shirley helped grow by finding a source of brown rice in Arkansas. Like the other new-wave co-ops of the ’70s, we stood on the shoulders of earlier generations once again—this time the farmers who had pioneered cooperative grocery stores, feed stores, electric utilities, and gas stations. We had no interest in profiting from our neighbors. We sold to them at cost.

There weren’t many of them—just the athletic Bryan who ate for good health, a hippie couple, and an older couple who lived nearby, Mr. and Mrs. O. One afternoon I woke up from a nap in the summer kitchen to the sound of incoherent moans and cries. A woman called repeatedly for her mother, and I heard her say, “There she is! I see her!” I heard other voices, too, of people attending to the woman. When I got outside, I learned that Mr. and Mrs. O had come to shop at our co-op, and Mrs. O had fallen down and stopped breathing. Otter had resuscitated her with CPR, and by the time I came on the scene, she was helping Mr. O get his wife into their car so that he could rush her to the hospital.

Mr. and Mrs. O had come from somewhere in the south. She loved pinto beans and couldn’t find them at either of the two grocery stores in town. After she recovered from whatever had caused her to collapse, the two of them came back often. They credited Otter for saving Mrs. O’s life, and their gratitude spilled over into kindness toward all of us. Lisyli told me once that Mrs. O took her aside one day and whispered something meant, we think, as a friendly word to the wise. She warned about our neighbors: “They say you’re prostitutes and worse.”

We laughed off that “worse” part. We were something. That’s for sure. As far as I was concerned, the ones who didn’t know could keep right on guessing.

Dianna Hunter is author of the book and radio series Breaking Hard Ground: Stories of the Minnesota Farm Advocates. She taught writing and women’s and gender studies at four universities, including the University of Wisconsin-Superior where she was a lecturer and director until she retired in 2012. She lives in Duluth, Minnesota.