In honor of the upcoming thirty-fifth anniversary of Joan M. Jensen’s publication of her landmark collection of primary documents,With These Hands: Women Working on the Land (1981), the Rural Women’s Studies Association sponsored a roundtable highlighting innovative uses of primary sources for studying rural women at the 2015 annual meeting of the Agricultural History Society in Lexington, Kentucky. This panel showcased recent research and discussed the unique sources employed to investigate the diversity of women’s experience in the rural United States and Canada. Today we are featuring the work of one of those accomplished scholars, Karen V. Hansen, which draws on her excellent recent book Encounter on the Great Plains: Scandinavian Settlers and the Dispossession of Dakota Indians, 1890-1930 (Oxford, 2013).

Indigenous Women’s Sources in Entangled Encounters

Karen V. Hansen

Brandeis University

Inspiration of Joan Jensen’s work

With these Hands interweaves narratives of different groups, always with an eye to concurrent histories, structures of inequality, and gender. It sets up what Gunlog Fur (2014) calls an “entangled” history. Fortunately for us, Joan Jensen has spent decades pursuing illusive paper fragments, long-disappeared narratives, and slanted accounts of farm laborers. She has interpreted them through layers of silence and distortion.

Jensen’s intersectional frame, as with her most recent book, Calling this Place Home, is exemplary in giving equal consideration to Native Americans, settler immigrants, Euro-Americans, and African American women in rural society. She never loses sight of the fact that women in different social locations can have profoundly different experiences, even when they share some important conditions of life.

Mapping Who Owns the Land

In my own quest to understand the lives of Dakota and Scandinavian women, especially with the scarcity of personal narratives, I sought whatever I could find that spoke to on-the-ground entanglements. I listened to stories of family history and mistreatment by the U.S. government. I scrounged through federal archives and found Dakota women defying dominant portraits of them. Cast as non-agriculturalists, they cultivated prize-winning, multi-acre gardens. Reported as recalcitrant housekeepers, some assiduously avoided monitoring by the federal field matron, while others cultivated her alliance and cooperation. Testimonies at federal hearings enumerate Dakota women’s charges against Indian agents, and they document women’s participation in tribal governance.

Underlying these accounts is a powerful story about land. No history of indigenous women can ignore the importance of dispossession and how it shaped everything subsequent: economic possibilities, Indian-white political relations, cultural practices, the meaning of land, and of course, how much land Native people could claim.

Entanglements—integration on the Reservation

The government legislatively structured the conditions of land taking via the Dawes Act of 1887. After its passage, Dakotas fervently lobbied Congress to increase the acreage allotted women. Through their efforts, allotments to women, including married women, doubled to 80 acres.

In a nutshell, after allotment of private property to individual Indians, like reservations around the country, the Spirit Lake Dakota Indian Reservation was opened to white homesteading. This map marks in red the lands ON the reservation (formerly misnamed, Devils Lake Sioux Indian Reservation) that were NOT allotted to Dakota Indians. In 1904, this swath of land was opened to white homesteading.

In that entangled space, Dakota women took title to their allotments. Their ownership is recorded via the handwritten names on historical plat maps.

This slide of the plat map of Eddy Township in 1910 is divided by a squiggly line, the Sheyenne River, which denotes the southern border of the reservation.

Map 3: Section of Eddy Township plat, 1910

In this enlarged view, I have marked in yellow those plots belonging to Dakotas, and blue, those owned by Scandinavians. As you can see at a glance, the blue and yellow squares are interspersed. Also, in this section of reservation, the blue outnumber the yellow.

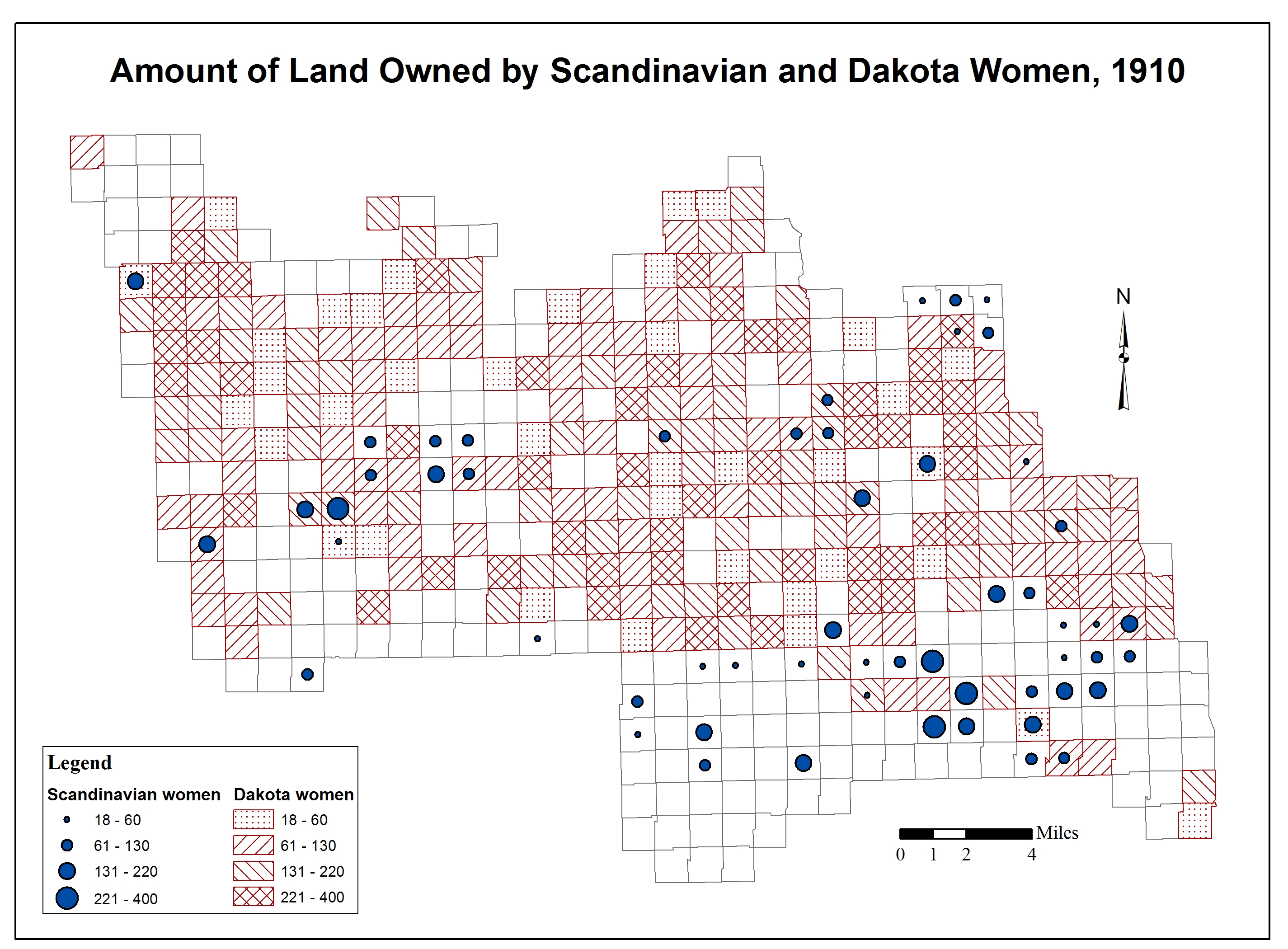

Women’s Landownership–1910

If you looked even closer, you would see more than a few women’s names: Kristen Wree; Anna Berg; Inga Erikson. Emma Sunkaska; Mrs. Blueshield; Mahpiyatowin.

In fact, in 1910, on the reservation as a whole, women were 38% of Dakota landowners. Among the Scandinavian settler-homesteaders, women constituted 12% of landowners. This was higher than all other Yankee and immigrant groups on the reservation, and in most of North Dakota. That said, in comparison to Dakotas, Scandinavian women made but a fraction of female landowners on the reservation.

This GIS analysis of the landownership data arrays the Dakota women’s land in red grid and Scandinavian women’s in blue dots.

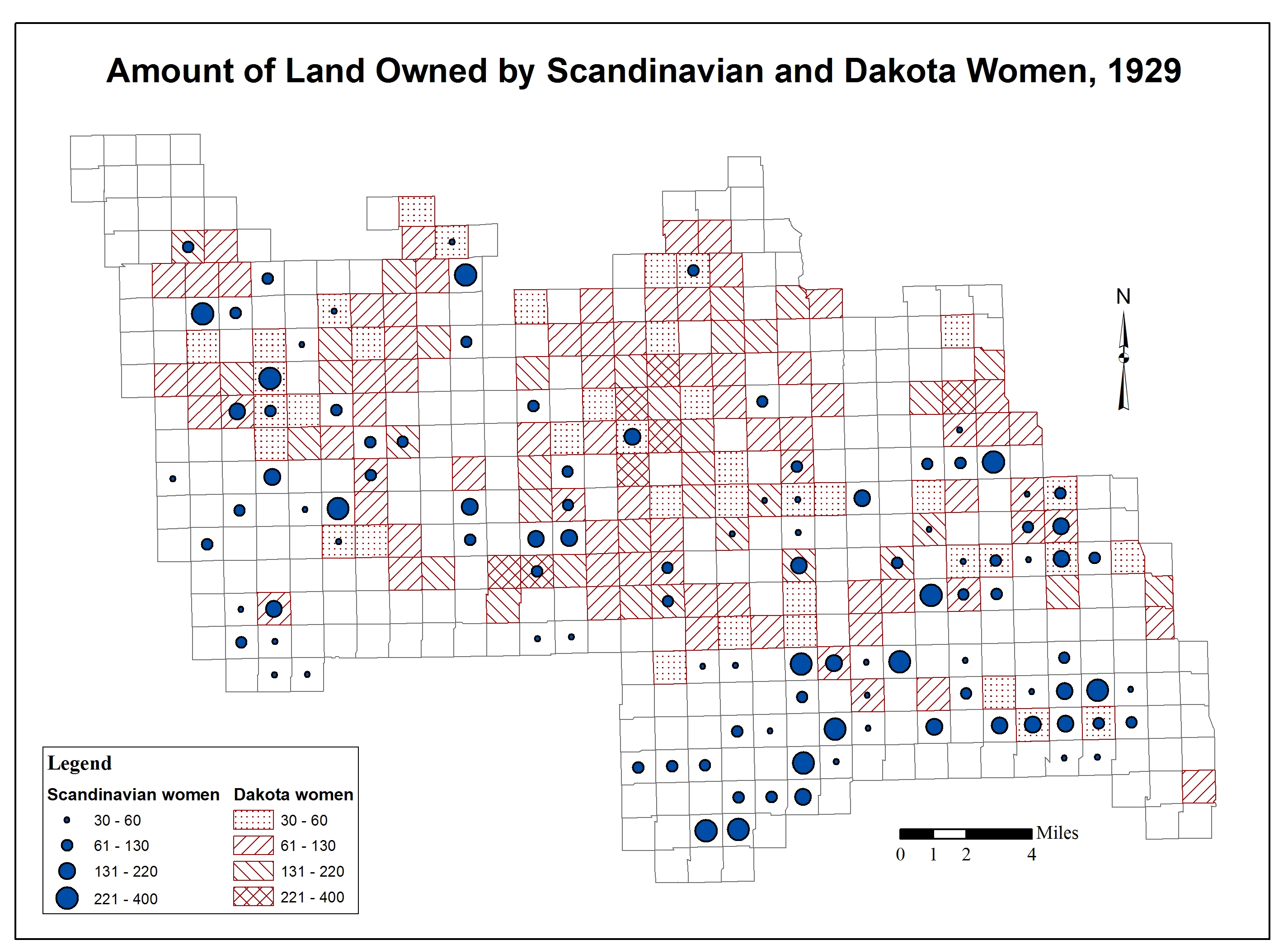

Women’s Landownership–1929

An updated analysis arrays the transformation of landownership just 19 years later. The map tells a story: Dakota women owned less land over time. Dakota women continued to be significant landowners in the tribe: 35% of those who owned land in 1929. But fewer Dakotas owned land, and they owned smaller parcels.

Their neighbors, Scandinavian women, accumulated land and became 24% of Scandinavian landowners by 1929. More women owned land; and they owned bigger parcels.

Given the fixed boundaries of the geographic reservation space, one group’s gain meant Dakotas’ loss. This is what dispossession looks like in the early twentieth century.

Women’s Agency—“Native Women Don’t Buy Land”

Dakota and Scandinavian women were active agents in this tug of war over land. Dakota women who sought to make their allotments yield nutrition and income required intentionality, fortitude, and no small amount of hard work. Once women were allotted land, not only did some make every effort to retain it, but some Dakota women, like Mary Blackshield, also bid on land and purchased it. She cultivated some of her land, rented some, and generated enough income to support her elderly mother and herself after her husband died. Some Dakota elders, like Eunice Davidson’s grandmother, admonished their people to hold onto the land.

Making a homestead claim on formerly uncultivated land, proving it up, living on it, was no casual accident. My analysis of the reservation reveals that Scandinavian women actively sought homesteads and land titles. And because they also bought land when they could, the number and proportion of women owning land increased over time.

Conclusion

In a Jensen-ian tradition, I have situated my research at the nexus of interactions between Dakotas and Scandinavian settler colonists. I have witnessed how their seemingly parallel lives—grounded in the land—intertwined and entangled. I have been challenged to search for new sources of evidence, to re-evaluate those I thought I knew, and to find new vantage points from which to re-interpret the taken-for-granted.

Joan Jensen challenges us all. And for that, I am extremely grateful.

To learn more about interactions between Dakotas and Scandinavian settler colonists, read Karen V. Hansen, Encounter on the Great Plains: Scandinavian Settlers and the Dispossession of Dakota Indians, 1890-1930 (Oxford, 2013).