A few thoughts on the long woman suffrage movement on the Northern Great Plains

~Molly P. Rozum, University of South Dakota

~Lori Ann Lahlum, Minnesota State University Mankato

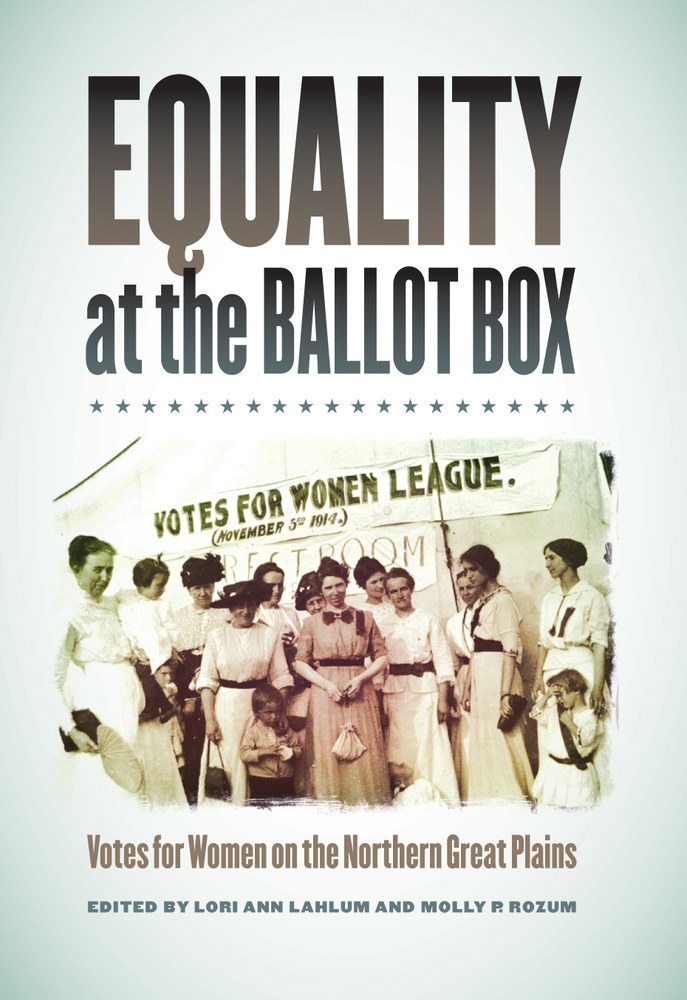

Editor’s note: Today we hear from the editors of a brand new book, Equality at the Ballot Box: Votes for Women on the Northern Great Plains, now available from South Dakota Historical Society Press. This blog entry is adapted from Rozum and Lahlum’s introduction to the volume.

Wyoming is often viewed as an outlier in the nation and on Northern Great Plains because it enacted woman suffrage in 1869—the first territory, and in 1890 the first state, to do so. The general woman suffrage movement in the Northern Great Plains states suggests, however, that only the successful result, not the impulse, should be seen as an outlier. Indeed, Dakota Territory considered woman suffrage in its 1868-1869 legislature. Prolonged territorial discussion of woman suffrage in all the Northern Great Plains states became important precursors for post-statehood efforts to secure voting rights.

As North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming looked toward statehood, woman suffrage supporters saw success on the horizon. Wouldn’t it be marvelous if North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming entered the Union as a body with woman suffrage rights? The summer and early fall of 1889 was an exhilarating time as the Northern Great Plains states petitioned the U.S. Congress for statehood. Spirited debates over the enfranchisement of women took place at all of the state constitutional conventions. National suffragists dared to hope. Opponents of woman suffrage throughout the region, and even some supporters, warned that including it in the new state constitutions could give Congress a reason not to admit the petitioning states or offer voters a reason to reject the constitution. As it turned out, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana joined the U.S. together in 1889, but with only limited voting related to school issues rights for women residents. In Montana women taxpayers could vote on tax and bond issues, a continuation of voting privileges from the territorial period.

Equality at the Ballot Box: Votes for Women on the Northern Great Plains, published in October 2019 by the South Dakota Historical Society Press, is the first volume to explore the long history of woman suffrage in Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and North Dakota from a regional perspective. For a brief time, Dakota Territory included parts of all four northern plains states. The states shared timing of settlement, long-resident Indigenous peoples, long territorial periods, large foreign-born immigrant populations, semi-arid grasslands, and three of them—eyeing Wyoming’s success—some fifty years of persistent woman suffrage activism. Still, each state’s suffrage movement had a unique trajectory. State-level political party machinations, post-Civil War national politics, railroad and brewer lobbyists, reform elements, and immigrant cultures combined and remixed to create different outcomes in various years. Each state witnessed many failed attempts to push woman suffrage through state legislatures. Montana’s only referendum in 1914 won, while North Dakota’s only referendum, also that year, failed. South Dakota failed too in 1914, as it had in 1890, 1898, and 1910 and would again in 1916.

Equality at the Ballot Box: Votes for Women on the Northern Great Plains, published in October 2019 by the South Dakota Historical Society Press, is the first volume to explore the long history of woman suffrage in Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and North Dakota from a regional perspective. For a brief time, Dakota Territory included parts of all four northern plains states. The states shared timing of settlement, long-resident Indigenous peoples, long territorial periods, large foreign-born immigrant populations, semi-arid grasslands, and three of them—eyeing Wyoming’s success—some fifty years of persistent woman suffrage activism. Still, each state’s suffrage movement had a unique trajectory. State-level political party machinations, post-Civil War national politics, railroad and brewer lobbyists, reform elements, and immigrant cultures combined and remixed to create different outcomes in various years. Each state witnessed many failed attempts to push woman suffrage through state legislatures. Montana’s only referendum in 1914 won, while North Dakota’s only referendum, also that year, failed. South Dakota failed too in 1914, as it had in 1890, 1898, and 1910 and would again in 1916.

Further, as Ruth Page Jones suggests in her contribution to the volume, school suffrage rights achieved during the territorial period and continuing into statehood became an important foundation for women’s political activism. For example, northern plains women— Laura Kelly Eisenhuth of North Dakota (1892), Emma F. Bates of North Dakota (1894), and Estelle Reel of Wyoming (1894)—became the first women nationally to be elected to statewide offices as state superintendents of public instruction (and South Dakota’s Kate Taubman only narrowly lost that position in 1896). Some women had been voting for years on school issues by the time the states had full woman suffrage, providing them important political training. The idea of woman suffrage, if not successful everywhere on the northern plains, existed as part of the region’s political culture until passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Northern Great Plains voices add texture to the national narrative, often reflexively Northeast, of the woman suffrage movement. Indeed, Barbara Handy-Marchello provides the first comprehensive account of the North Dakota suffrage movement since a student at the University of North Dakota wrote an undergraduate paper on the topic in 1951. Similar to Emma Smith DeVoe, who left South Dakota after its failed 1890 referendum to help other western states to victory, Kristin Mapel Bloomberg argues the suffragist Cora Smith Eaton honed her later successful suffrage activist tactics in North Dakota. Jennifer Helton suggests a similar intersection for Theresa Jenkins, a voter in Wyoming, who participated in Colorado’s 1893 successful woman suffrage campaign. Effectively, women developed sophisticated tactics during the long woman suffrage movement on the plains, which in turn influenced the suffrage movements of many states and their ratifications of the Nineteenth Amendment. Northern Great Plains women’s skills made a difference in the success of the national woman suffrage movement. Still, Paula Nelson shows many rural women of modest means—again, rather than the wealthy northeastern “Antis” of image—remained committed to a conception of moral, nonpolitical, womanhood as a cultural force in this agricultural region.)

On the Northern Great Plains, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) played a crucial role in suffrage successes and emerges as a distinguishing feature of the region’s movement, despite considerable pressure from the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) on the region’s suffrage leadership to separate prohibition from conversations about woman suffrage. Not only was the organization embedded in local communities, it became the only consistent suffrage organization in the region over the long battle to enfranchise women. In the three states without full woman suffrage, membership in the WCTU far exceeded membership in other suffrage organizations, and the WCTU trained women to speak publicly in favor of woman suffrage—women like Kate Selby Wilder in North Dakota, Mary Long Alderson in Montana, and Emma Smith DeVoe in South Dakota. As a result, small towns throughout the region had access to suffrage speakers. Many male voters in the Northern Great Plains states supported temperance and prohibition, and WCTU speakers frequently found audiences open to their message. The power of prohibition was clear when North Dakota and South Dakota both entered the Union as dry states in 1889. Activists in national suffrage organizations often failed to recognize that this linkage could be an asset in the region. To be sure, suffragists like Mary (“Mamie”) Shields Pyle of South Dakota and Jeannette Rankin of Montana opposed linking these causes as a strategy. Nonetheless, the connection between woman suffrage and prohibition often helped convince men that they should support suffrage. More importantly, tethering prohibition to suffrage prompted women to advocate for female enfranchisement.

The large number of European immigrants in the Northern Great Plains states also influenced suffrage debates in the region. Much of the strategizing for suffrage campaigns concerned how to win the vote in predominantly foreign-language-speaking ethnic communities. Although much of the settler population had migrated from nearby states, the Northeast, and Canada, the region had significant foreign-born populations from Germany, Bohemia, England, Ireland, Norway, and Sweden, as well as large numbers of Russian-born Germans in the Dakotas. Local suffragists and national leaders often disagreed over the potential of immigrant voters. As Sara Egge contends in her focused look at ethnic and woman suffrage, far too many eastern suffragists saw immigrants as impediments, while local workers, though often frustrated in their ability to reach into these ethnic enclaves, viewed them as opportunities for suffrage success. With so many immigrants and children of immigrants on the Northern Great Plains, they would clearly play a role in suffrage votes, and debates about immigrants remained a persistent feature of woman suffrage in the region. A pro-suffrage Scandinavian Temperance Society resolution in 1898 and an anti-suffrage 1910s German language newspaper ad suggest the complex intersection of ethnicity and woman suffrage on the Northern Great Plains.

Equality at the Ballot Box is part of the growing scholarship that links woman suffrage and region while providing an important corrective to the national narrative centered on Eastern suffragists. We began this project with the goal of celebrating the centennials of woman suffrage in the Northern Great Plains States and showcasing how studying woman suffrage in this region could shed new light on the broader woman suffrage movement in the United States. While Equality at the Ballot Box offers new perspectives on the movement nationally and in the West, there are still questions to be answered and topics to be researched. We intend to continue the discussion, and we hope others will join us on the journey.

(This blog is modified from the Introduction of Equality at the Ballot Box: Votes for Women on the Northern Great Plains.)