“This is all the home I now have”: Deserted and Widowed Homesteaders

Rebecca S. Wingo, Macalaster College

Homesteading the Plains: Toward a New History is a co-authored book by Richard Edwards, Jacob K. Friefeld, and Rebecca S. Wingo. Their book is now available through Amazon and the University of Nebraska Press. The authors encourage you to visit their website to explore what they advance as new understandings of the Homestead Act that challenge and provide nuance to some of the accepted scholarship about the law. There you will also find their data, maps, and graphs of the network of witnesses in each township. The following is an adaptation of their findings on deserted and widowed women homesteaders in Nebraska presented by Rebecca S. Wingo at the Western History Association conference in November 2017.

Homesteading the Plains: Toward a New History is a co-authored book by Richard Edwards, Jacob K. Friefeld, and Rebecca S. Wingo. Their book is now available through Amazon and the University of Nebraska Press. The authors encourage you to visit their website to explore what they advance as new understandings of the Homestead Act that challenge and provide nuance to some of the accepted scholarship about the law. There you will also find their data, maps, and graphs of the network of witnesses in each township. The following is an adaptation of their findings on deserted and widowed women homesteaders in Nebraska presented by Rebecca S. Wingo at the Western History Association conference in November 2017.

Edward Wells, a blacksmith in Broken Bow, Nebraska, fell ill in early December 1887, the same month he was scheduled to finalize his homestead claim. On December 5th his two witnesses appeared at the land office during his scheduled appointment to testify that he was unable to make the hearing. Abner Brown stated of Edward, “He now requires constant daily nursing—he is not able to lie down and sleep but must sit in a chair to sleep—cannot wear anything but large slippers on his feet.” The land agent pushed the hearing back until December 15th. In his stead, his wife Delila Wells appeared and testified that her husband had died. Her testimony was not enough. Her witnesses had to verify her statement. Thomas Parrott, a witness and boarder on the Wells’ property, said that he,

knows from personal knowledge that the Claimant said Edward J. Wells is now dead, that he was personally present in the house of said Claimant on above described land at the time of the death of said claimant – that said claimant died sitting in a chair, at 3 o’clk and 15 minutes P.M. on Friday, December 9th A.D. 1887 in the said house on their said land–that he has been personally acquainted with said Edward J. Wells since the year 1881 and that he is positive, and cannot be mistaken, that the person whom he saw die as aforesaid was the identical person who made original Homestead Entry No. 9497.

When Wells signed her “X” on her final claim, the land agent signed the final affidavit “Edward J. Wells by Delila Wells his wife,” but then smudged out “wife” and wrote “widow” instead.

The last days of Edward’s life were hard on Wells and complicated even more by the necessity of complying with the General Land Office’s bureaucratic timeframes and appointments. Because of her clear hardship, Wells’s male neighbors and friends came together to help finalize her claim. Her testimony speaks to determination and cooperation as well as sadness. When asked about her residency on the land, she responded, “Actual & continuous—Have had no other home or place to live.” She continued, “I want this land for my own personal home—this is all the home I now have.”[1]

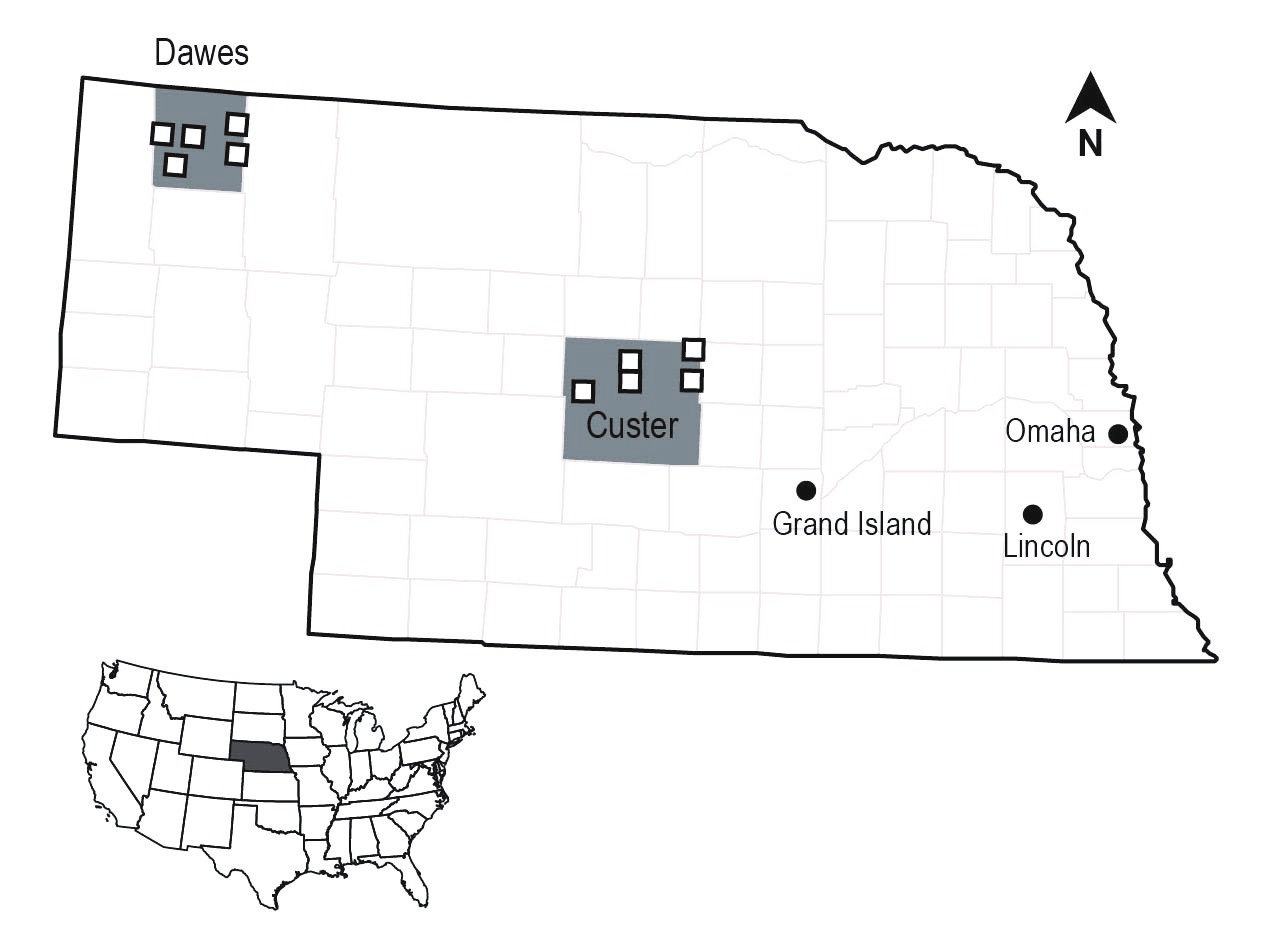

Map of the townships in Custer and Dawes counties that comprise the Study Area. Image by Katie Nieland.

Wells was one of 64 women in our study area who proved up their homestead claims and received title to their land. They comprised 10.3 percent of all study area homesteaders, which is a percentage roughly on par with other samples of women homesteaders across the West.[2] Our study area included 621 homesteaders in ten townships in Custer and Dawes counties, Nebraska, where the majority of the land transferred from the public domain via homesteading. That said, there were more than 64 women using the Homestead Act to build homes, farms, and futures. There were 407 married male homesteaders, or, 407 other women homesteaders not counted because of nineteenth-century conventions. We know from many other accounts that wives were critical to the success of homesteads; their income from sales of butter and eggs often saved the family from starvation when the crops failed or were destroyed. In many cases they also joined men in the heavier work in the fields.[3] While this blog focuses on a few of the 64 women who homesteaded in their own names, we should not lose sight of the larger group of married women who also struggled to succeed at homesteading.

And among those 64 women, widowed and deserted women homesteaders occupied a strange legal space, and—like Wells—often relied on cooperation and support from male neighbors. Within our Study Area, the local community often rallied to support nontraditional women’s homestead claims, particularly inheritance and desertion. However, these women also helped each other in interesting ways.

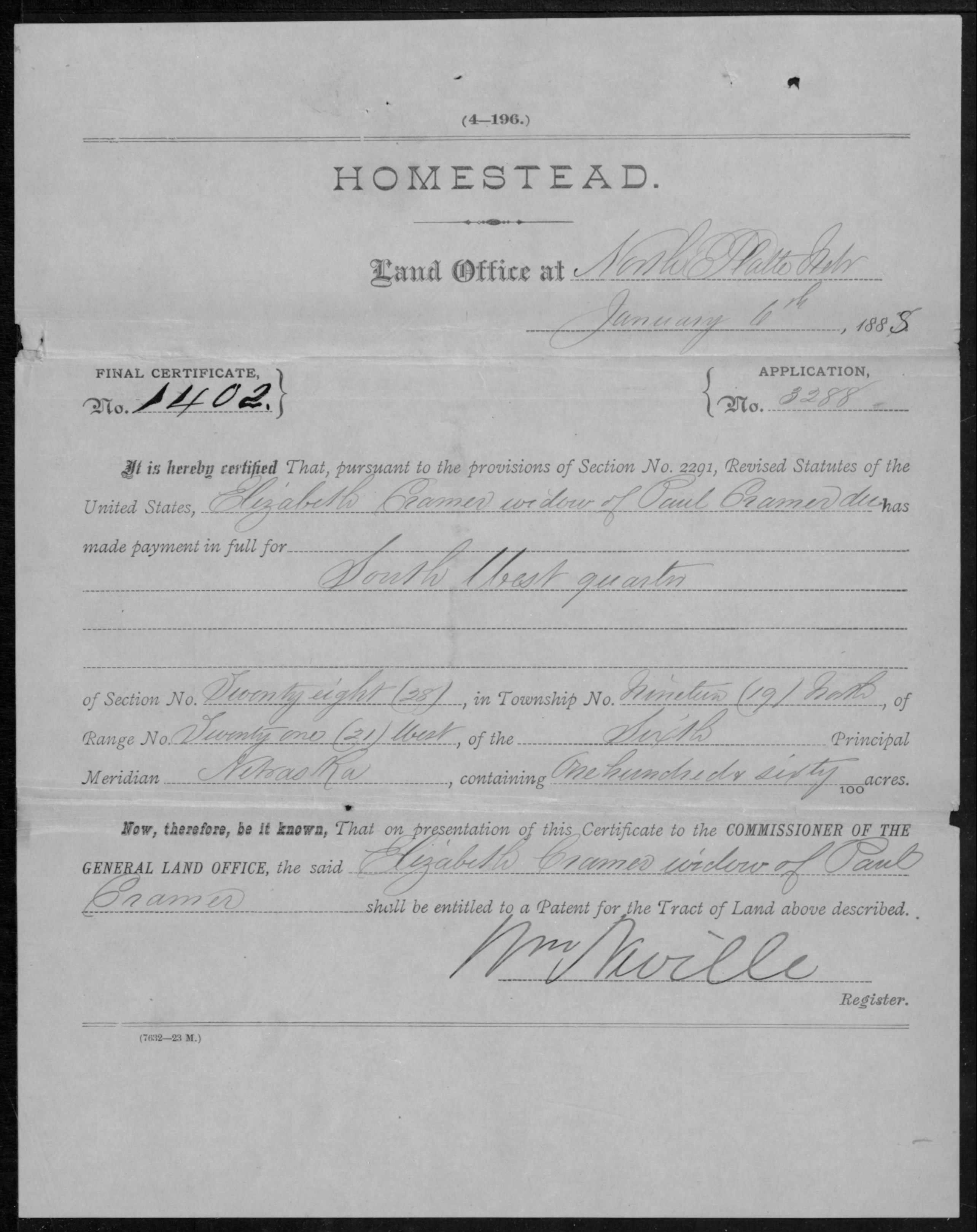

A page of Elizabeth Cramer’s application of final proof at the North Platte Land Office. Image courtesy of Fold3.com.

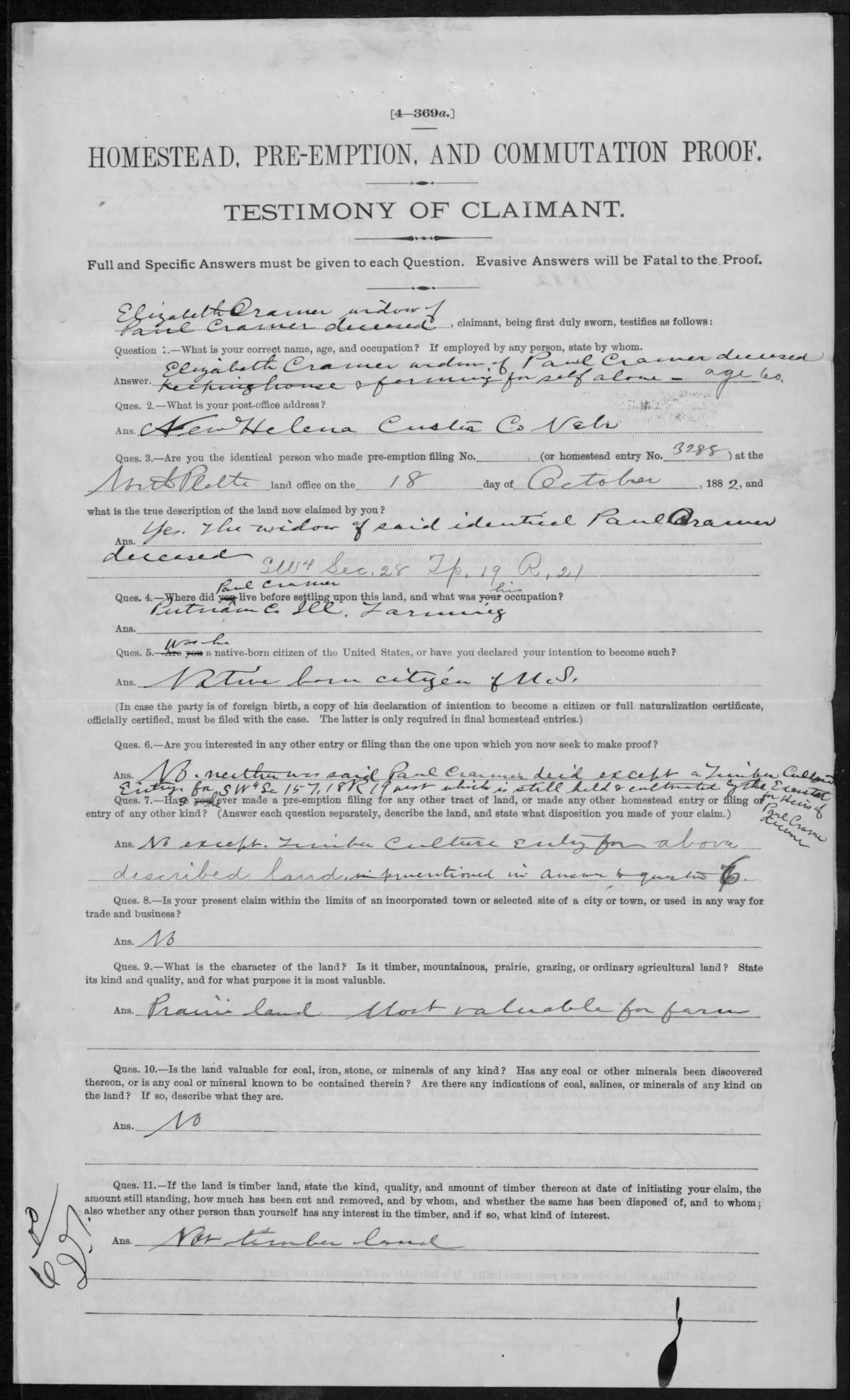

Inheritance cases like Delila Wells’—whose witnesses had to verify her claim that her husband was indeed dead—were not all that unique. For example, Elizabeth Cramer’s husband died in October 1886, and approximately one year later she sought to prove up the inherited claim. Her statement and those of her witnesses pertained to her deceased husband, not to her own right to the claim. Cramer further had to prove to the Land Office that she was in fact the widow of Paul Cramer. One of her witnesses testified when asked, “Have known her for years. Is the person she claims to be.” Complicating matters, she was unable to reach the land office on her scheduled date due to a severe storm, provoking yet another sworn statement from her witnesses validating her delay. Without the testimony of her neighbors as to her identity, intent of claim, and reason for her tardiness, she may well have lost her land.[4]

Elizabeth Cramer’s sworn testimony upon final proof at the North Platte Land Office. Image courtesy of Fold3.com.

Cramer identified her profession as “Keeping house & farming for self alone,” but we also catch a glimpse of the importance of her community: she made additional money after her husband died keeping house for a neighbor. During her time of need, her neighbors ensured her a steady income and her right to the homestead. As inheritance cases like Cramer and Wells demonstrate, support from neighbors and others in the local area was often crucial for a claimant to secure her land patents.

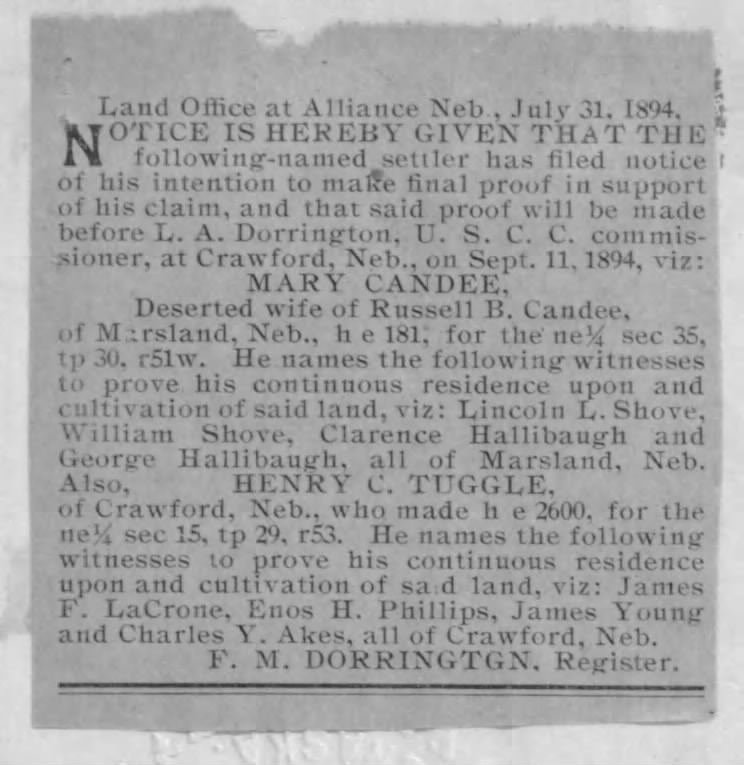

Desertion occurred in only two instances within our Study Area. These women had trouble asserting a right to the land because of both misinformation and legal barriers. They, like their widowed counterparts, relied on the advocacy of their male neighbors to secure their patents. For example, Mary Candee and her husband, Russell, built their homestead in Dawes County in 1887. Twenty-seven years old at the time, Candee found herself running the homestead alone after Russell abandoned her and their four children in April 1891. Candee continued to reside on the land and make improvements in compliance with the law, but she failed to understand the legal nuances of the time limits to file.

Mary Candee’s Proof of Posting. Image courtesy of Fold3.com.

Candee knew that without finalization, her husband’s claim to the land expired after seven years. She wrongly concluded that she had to wait until Russell’s claim expired to re-file on the land, then wait five more years to prove-up and earn the title in her own name. That would total 13 years of continuous residency with no title to show for it. According to the law, however, if she could simultaneously demonstrate her husband’s failure to prove-up and her own success, she could count all her years toward her own claim. This stipulation meant that her claim would expire when Russell’s did—in 1894 instead of 1899 like she believed. Candee nearly missed her window. She realized this only in the seventh year. Two men—Lincoln and William Shove—testified on her behalf that her residence was continuous since 1887, her husband did indeed desert her and her children, and her improvements were legitimately hers alone. Candee undeniably worked hard to improve her claim, which included a buggy shed, cave, frame barn, hen house, and log house worth approximately $350. Without the support of her neighbors and the leniency of the land agent, however, Candee easily could have surpassed the time limit to file, and lost the land and her improvements to another settler.[5]

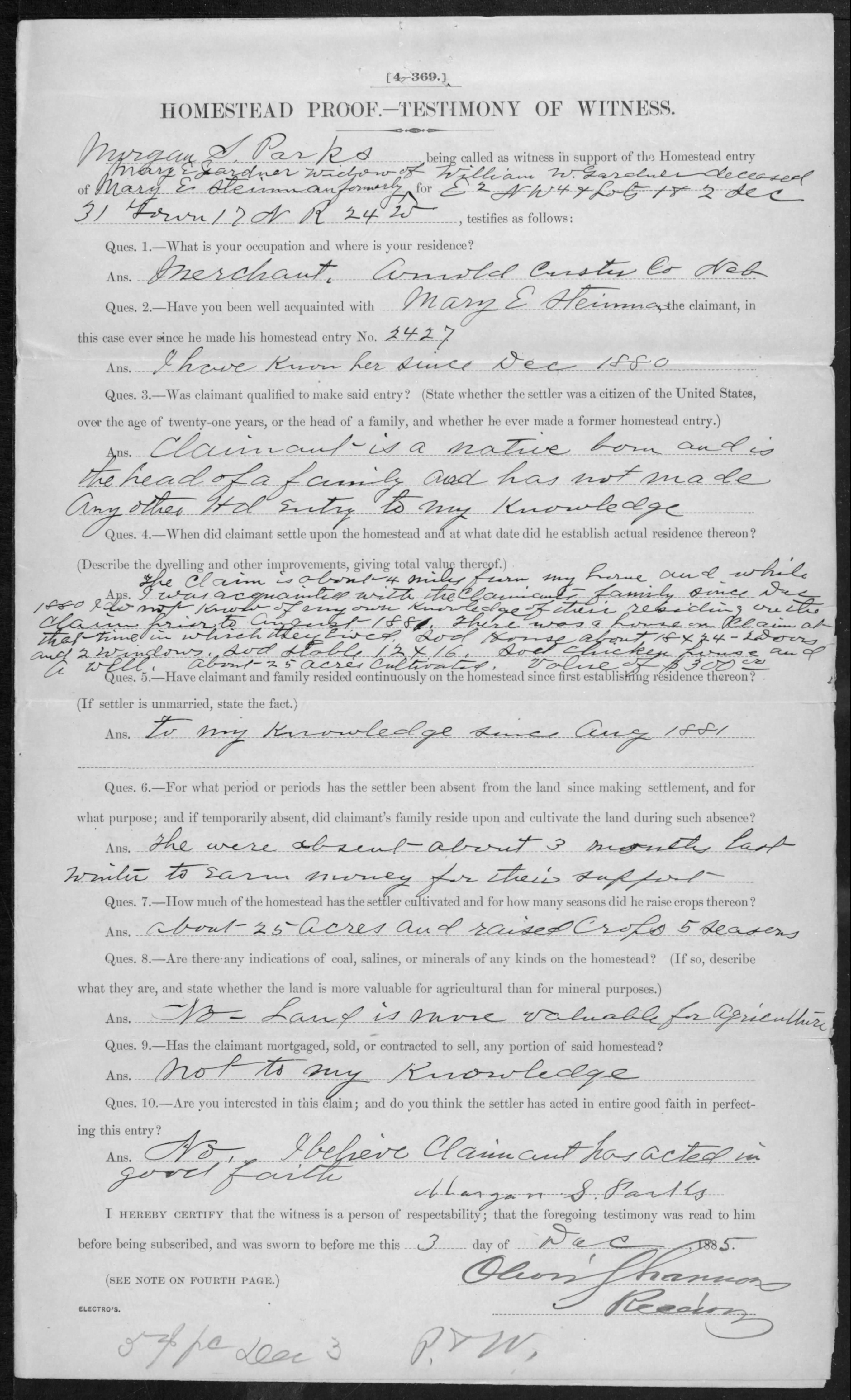

In the other desertion case, Mary Steinman of Custer County was left with an inherited homestead and four children to care for after her husband, William Gardner, died in 1881. She remarried to Jacob Steinman in 1882. In 1883 Jacob abandoned her, and thanks to 19th century law, Jacob’s name was now on the claim. Not to be stymied by two marriage failures (although I’m sure William didn’t mean to die), Steinman swore an affidavit at the Land Office on her own behalf: “For the last two years my husband…has deserted me and has not contributed to myself or family.” Interestingly, her two witnesses both testified that she was “formerly” the wife of Jacob, and further testified to her status as “head of a family,” shifting her claim status from Widow/Remarried/Abandoned to Head of Household in order to prevent Jacob from returning to claim the property. In other words, her neighbors helped her accomplish a legal status that she would otherwise have been denied. Steinman’s case demonstrates not only the power of community, but also the necessity of it.[6]

Testimony of one of Steinman’s witnesses that she is the “head of a family.” Image courtesy of Fold3.com.

There’s a thread throughout the examples I just gave about the importance of men in women’s homesteading. Just marinate in that irony for a second. Our data, however, shows that women were intentionally pushing forward their own social and legal liberation through the act of witnessing. Out of 557 male claimants, only in two instances did men use women as witnesses. Women, though, called upon other women as witnesses at over ten times the rate as men. With little exception, women witnesses provided the same information in the same vernacular as male witnesses, leaving no discernable difference between male and female testimony. Whether or not to use a male or female witness would seem to have been decided by social norms, or perhaps the preferences of the local land agents.

Though women were rarely listed as possible witnesses, and even more rarely called to testify, Dawes County contains the only instance in which women serve as both of the witnesses, in Josephine Lane’s claim. They were all widows. Lane asked Martha Bowdish and Ellen Abbott to testify on her behalf, and used them rather than the two men listed in her Proof-of-Posting. Bowdish and Abbott testified on behalf of Julius, Lane’s husband who had died on April 19, 1891, before he could finalize his claim. The witnesses discussed “his” improvements (worth $1500) for “his” family on “his” land. Rather than acknowledging the property as inherited by Lane, the women gave testimony for the deceased. What’s more interesting is that at the time of each of their proofs, Bowdish, Abbott, and Lane had geographically closer male neighbors. They bypassed them in favor of choosing their female friends nearby.

Delila Wells’ words are haunting: “This is all the home I now have.” But for some women, the homestead was more than a home. It was a place to challenge the status quo and their own place in it. The use of women as witnesses in the claim process, even though rare, indicates social as well as legal change, spurred on by women, for women. Women homesteaders—not just those who claimed land in their own names—often formed the heart of social activity on the Great Plains, but they hardly occupied an equal place in the legal sphere. And that went double for widowed and deserted women, many of whom started the process as part of a married partnership. Women pressed the bounds of imposed limitations with and sometimes without the help of their male counterparts. The women homesteaders in the Study Area also press the bounds of current homesteading scholarship, suggesting that widowed women may have more commonly taken advantage of a presumed single woman’s law than previously thought.

[1] Delila Wells, Homestead Records: North Platte Land Office, Township 17N, Range 24W, Section 33, Fold3.com Digital Archive, accessed June 26, 2014, http://www.fold3.com/image/283893798/.

[2] See in particular, Sheryll Patterson-Black, “Women Homesteaders on the Great Plains Frontier,” Frontiers 1 (Spring 1976): 67-88; Elaine Lindgren, Land in Her Own Name: Women as Homesteaders in North Dakota (University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 52; and Paula Bauman, “Single Women Homesteaders in Wyoming, 1880-1930,” Annals of Wyoming 58 (Spring 1986): 39-53.

[3] On the importance of the homesteader’s wife’s work, see Barbara Handy-Marchello, Women of the Northern Plains: Gender and Settlement on the Homestead Frontier, 1870-1930 (St. Paul: Minnesota State Historical Society, 2005), Chapter 3.

[4] Elizabeth Cramer, Homestead Records: North Platte Land Office, Township 19N, Range 21W, Section 28, Fold3.com Digital Archive, accessed June 26, 2014, http://www.fold3.com/image/283895307/.

[5] Mary Candee, Homestead Records: Alliance Land Office, Township 30N, Range 51W, Section 35, Fold3.com Digital Archive, accessed June 26, 2014, http://www.fold3.com/image/273498176/.

[6] Mary E. Steinman, Homestead Records: North Platte Land Office, Township 17N, Range 24W, Section 31, Fold3.com Digital Archive, accessed June 26, 2014, http://www.fold3.com/image/283873664/.

Pingback: What I’m Reading 7 | History in South Dakota