Agrarian Women and the Welfare State

Sommestad, Lena, translator Grey Osterud. Agrarian Women, the Gender of Dairy Work, and the Two-Breadwinner Model in the Swedish Welfare State. New York and London: Routledge, 2019.

Review by Sally McMurry, Professor Emerita of History, Penn State University

The point of this book is to demonstrate the “significance of rural womanhood in the formation of Sweden’s gender-egalitarian welfare state in the early 20th c.” and to demonstrate the importance of “women’s gainful labor and organized activism to Sweden’s citizenship-based social policies, which enabled married women to combine childrearing with breadwinning.” (unpaginated frontispiece)

The first sections show how milk processing was women’s work and how it was connected deeply to cultural notions of gender, lactation, independence, and control of work. In the preindustrial era the occupation of dairymaid was highly skilled and respected; its scale and nature varied regionally. In the late 19th century dairying began a transformation that involved first centralization, then mechanization. This change was accompanied by the entrance of men into the work, facilitated by the male association with machinery and with science. In this new environment women still held a place but it was more limited than before; for example, they could become “county dairymaids,” who were given a mostly practical education and worked in smaller enterprises. Another wave of restructuring in the 1930s relegated women to “lower status jobs in larger dairies, no matter how well educated, highly skilled, and experienced they might be.” (35) “Open conflict” replaced the older, more fluid, slower, and more egalitarian environment. Dairy work was “recoded” as masculine and men dominated both numerically and in terms of power.

Lena Sommestad argues that despite this masculinizing trend, the persistence of women well into the industrial era, along with a strong historical memory of agrarian women as productive workers, helped to shape the adoption in Sweden of what she calls the “dual breadwinner” model of the welfare state, that is, policies based not on gender but on citizenship. For example, rather than pass protective labor legislation aimed only at women workers, the Swedish eight hour law applied to all workers. Another example is a pension system that was not tied to formal labor market participation; married women received pensions in their own right. After the Second World War, massive rural to urban migration occurred. In this new setting rural pasts were still close and influential; “feminists could use language that resonated with widely held images and memories of rural women as sturdy farmers, capable dairymaids, and good mothers.” (136) By the 1970s, the dual-breadwinner welfare state extended to publicly funded child care, individual taxation, and parental leave policies.

Other important factors contributed to the rise of the dual breadwinner model. Massive male-heavy outmigration in the 19th century had left many women single for life, and perforce they engaged in productive labor. As well, the country’s general poverty and relative lack of social stratification compelled most women to engage in both productive and reproductive labor, whether they lived in urban or rural settings. Demographic factors were important too, whether high birth rates in the 19th century that helped to force outmigration, or the historically low birth rates of the Depression era. Finally, Sweden’s population distribution was critical. In the 1930s and 1940s Sweden still had a majority living in rural places. As Sommestad puts it: “Sweden’s agrarian character made universalism a necessity, not just a political preference.” (127)

Sommestad concludes that “the gender division of labor, the valuation of women’s work, and the complex relationships between paid employment and caregiving are socially constructed and have been transformed over the previous century. Looking at Sweden makes that process visible.” (139) Through deft handling of a varied body of primary source material (interviews, photographs, printed sources, statistics), she persuasively shows that Sweden is indeed a notable case that helps to isolate various factors with particular clarity. Sweden’s experience sheds light on far broader trends in the West. We see disentangled the varied contributions to political choices made by class, gender, demography, and social structure. Sommestad’s chief aim is to connect Swedish dairy women’s experience to the dual breadwinner model, but she does this carefully so as to integrate gender into a broader explanation rather than to propose it as a narrow or monolithic factor.

Sommestad’s work is a model of clear thinking. For example, she is able to show that men and women with identical educational opportunity and attainment had different career paths in Sweden’s dairy industry, thus demonstrating definitively how gender discrimination operated. Another good example is the way gender concepts were manipulated with regard to technology. “Indeed,” she points out, “there is something strange about shifting from women to men just when technological change made muscular strength much less important…” (45) Instead, “managing machinery” became a “masculine path into dairy work” (111) and the reality of women’s physical strength was conveniently overlooked.

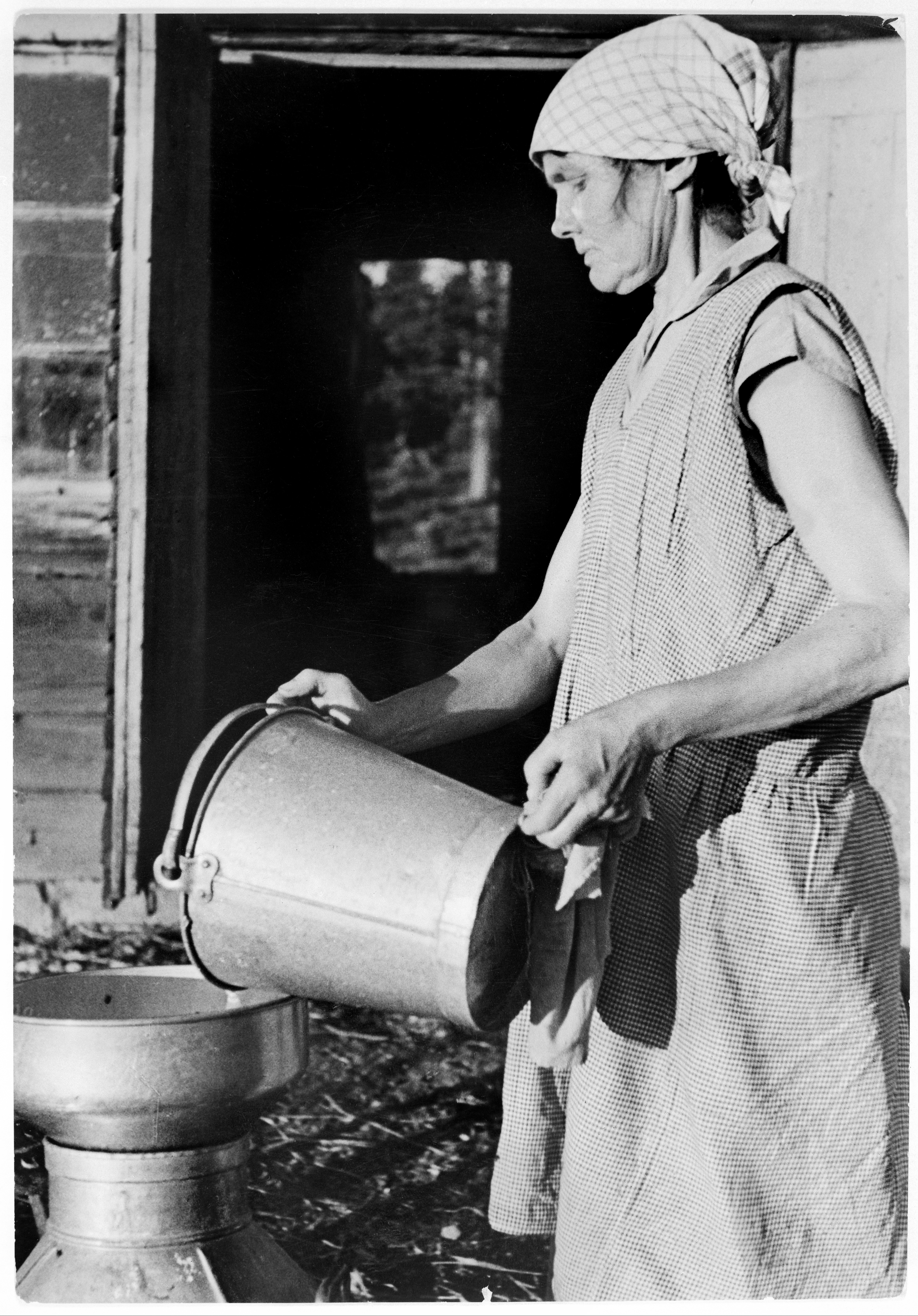

Gunnar Lundh, “Woman straining milk on a farm in the coastal area of Stockholm County in 1935.” In the collection of the Nordiska Museet, Stockholm, Sweden, NMA 0000173.

Collective memory had a crucial role in preserving older ideas of womanhood that in turn informed broad support for the dual-breadwinner model in Sweden. Urbanites reared in the country found ways to hold on to positive memories of women as “sturdy farmers, capable dairymaids, and good mothers.” (136) It would be interesting to further plumb how this memory worked. Did it function as a form of resistance to masculinization, whether in the dairy industry or more broadly? It seems as if perhaps these memories might have also served to counter standard Western stereotypes of women. A whole generation of city dwellers shared common recollections, but it seems notable that the people cherished and nourished these rural memories rather than discarding them. In the United States, for example, rural to urban migration was led by young women, and if anything positive notions of agrarian life were rejected rather than preserved.

Another potential avenue for further inquiry involves landscape and space. Sommestad notes some fascinating instances where spatial organization facilitated and reflected women’s independence. For example, young dairywomen spent summers in the mountains with the pastured cows, often with no males present. In the preindustrial context the cowshed was an exclusively women’s space. Could historical buildings and landscapes be utilized as primary source material for a deeper understanding of how gender worked in Swedish agrarian settings and later in the industrial dairy? Vernacular architecture studies has developed a substantial toolkit of analytical devices that could help. For example, in the United States women’s claim on barn space varied regionally, but always was more tenuous than in Sweden.

All in all, this volume is a welcome contribution. It brings together previously separate work in such a way that the completed whole is considerably greater than the sum of its parts. It ably addresses critical issues of interest to anyone who studies rural women.

Editor’s Note:

This volume presents Lena Sommestad’s research translated into English and edited by Grey Osterud. Read more about this RWSA international collaboration here.