Harriette Cushman: A Life in Poems

Amy L. McKinney

Associate Professor of History, Northwest College, Powell, Wyoming

I first started researching Harriette Cushman for the RWSA conference in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Joan Jensen organized a panel on rural women as “New Women” and Cushman was an excellent example of a professional woman in agriculture. She was the first woman hired as a topic specialist for the U.S. Cooperative Extension Service and Home Demonstration, serving in Montana from 1922 to 1955 as the poultry specialist. She exemplified the idea of the “New Woman” in many ways. She earned a college degree; experienced economic independence through her career in the extension service; traveled extensively by herself; enjoyed the outdoors and routinely went hiking, camping, and horseback riding; and maintained social independence by remaining single.

Harriette Eliza Cushman Papers, 1893-1978, Collection 1253, Special Collections, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana.

Most of my research on Cushman so far has focused on her as a “New Woman” and her professional career including her efforts in organizing a turkey cooperative, spearheading egg marketing, designing a chicken house, and overseeing a multi-faceted poultry program for Montana. As I continue to research her, I wanted to move beyond her professional life and peel back the layers of her personal life. Thankfully in addition to her professional papers, her collection includes boxes of letters she wrote to her parents and other personal writings. Cushman was a very intelligent and intellectual woman who had a passion for poetry and literature. Her parents encouraged and fostered her love of poetry. When she first started college at Mt. Holyoke she wanted to be a writer, but she excelled at science and transferred to Cornell University where she earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and bacteriology 1914. This led to her career with the extension service.

Although she loved her job, it was not her passion. Writing continued to be her true passion throughout her life. Cushman looked for ways to continue writing where she found comfort and a way to express herself. She wrote to her parents that she did “things for myself. That is poetry.”[1] This initial exploration of her poetry focuses on the types of poems she wrote and why she wrote. Her letters home to her parents were dotted with poetry, mainly what she had written, but she also wrote poems from other authors she thought her parents would enjoy. One avenue of her inspiration came from her extensive travel for work where she averaged one hundred days per year in the field. She worked long hours but always took time to write whenever she had the chance, whether that be travelling on the train, waiting for meetings with farmers or county agents, taking a break in the office, or writing in her time off at home. She had dreams of being published and wrote her parents that she “[had] been thinking it would be nice to make a collection of my poems and call it ‘Follow Me’ It would have an introduction saying that I go about the state. Sometimes on a prairie good roads and bad over mountains. I see poverty and ease. Ugliness and rare beauty. To have such lodge podge together. ‘Follow Me’ would explain and in a way cement the thing together.”[2]

One poem that brings to light her travels and how she saw the state is the poem “Abandoned Mail Boxes”

Where grass grown whell [sic] ruts meet the range

abandoned boxes stand like lopped off crosses

etched against the sky

and brace themselves against the prairie winds

which buffet them and sand the wooden grain

of lidless frames to a patina grown grey and deep.

No postman passes by.

The gophers burrow at their feet

and gnaw the rotting wood.

No rider stops.

These boxes have no tryst to keep.

They are like crossroad crosses set

for those who’ve hastened their own deaths

and can not rest in consecrated ground

but for eternity must sleep a troubled sleep

And yet last spring

a blue bird built in one.[3]

Travelling to every corner of the state Cushman saw the many abandoned homes, yet she saw the hope of a new nest expressing her belief in the future of Montana.

Cushman constantly looked for ways to be published. She mainly published in local newspapers and later the publication from the Montana Arts Institute. Although she was happy with being published in these local sources, she set her sights for more nationally recognized publications. She was especially encouraged by the Montana State University publication “The Frontier” which she believed was “developing a truly national reputation.” She met with the chair of English department who she stated gave her good constructive criticism. Getting published in “The Frontier” would be a stepping stone to a writing career and she wrote her parents “oh how I would like to be able to write. Even if I had to lower my standards of living considerabl[y], there would be a great deal more satisfaction.”[4]

She longed to be able to write full time. One of the reasons she remained single was the freedom for intellectual pursuits. She explained that she wondered “if one man’s love would be satisfying. It is terribly spoiling for a woman to grow up and be independent. She is sure of her own livelihood. Then she can choose from her various friends for different wants. … I realize I think a great deal of a great many of my friends and yet I don’t think I care to give up my freedom for any of them.”[5] Cushman rarely mentioned a desire to be married, except if it gave her a chance to write, stating that “somehow if I ever marry I want to stay at home. Well, I can, for I have some things I very want to do and that is write.”[6]

Her persistence showed results and she became known for her poetry by friends and the community. She expressed a desire to perform her poems for local groups and was invited by the AAUW and other women’s organizations to read her poems at their meetings. In 1941 Cushman was even asked to perform on the radio, although she was not impressed when the radio station suggested musical accompaniment. Sometimes the expectation to write took away from the joy of it. She often spent time in the mountains with friends and stayed at a friend’s cabin which had a log book for guests to sign. Cushman wrote to her parents that “Since I have been going up to camp, they expect me just turn on the poetry. I thought they would forget this time, but no such luck. The last day they said “where’s the poem” so I retired behind the tool house and communed with a chipmunk.”[7]

One area of inspiration for her poetry came from her work with Native Americans. The Blackfeet honored Cushman by giving her the name Petapoyea, or Eagle’s Word. Cushman wrote that “they wanted to put something about a bird in my name … because [they believed] what I said carried conviction and was strong.”[8] In 1955 she was officially adopted into the tribe. After her retirement from the extension service Cushman worked tirelessly to start a Native American center at Montana State University and donated a considerable amount of her estate to a scholarship for students. Her poems on Native Americans focused primarily on ceremonies like Sun Dances and ways of life. One poem in particular reflects her understanding and respect for native culture is entitled “No Brats”

Along a street in Havre

a woman yanked a screaming brat.

His tentrumed [sic] body stiffened as he yelled.

“Don’t act like a wild Indian,” she shrieked.

“Four Souls”, a native Cree, in white man’s garb,

(she had not noticed him)

Stepped in front of her,

“Madam, Indian children do not act that way.”[9]

Cushman even included poetry in her professional writing in her annual reports for the extension service and turkey letters. She lamented the overlooked place of chickens in Montana’s economy in “The Forgotten Hen,” and how mining, sheep and cattle over shadowed chickens even though they “[paid] the grocery bill.”[10] She also examined how she spent her time in an untitled poem showing the extensive time she dedicated to turkey marketing. She also included poems that reflected the seasons, including one entitled “Fall is Here.”

Harriette Eliza Cushman Papers, 1893-1978, Collection 1253, Special Collections, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana.

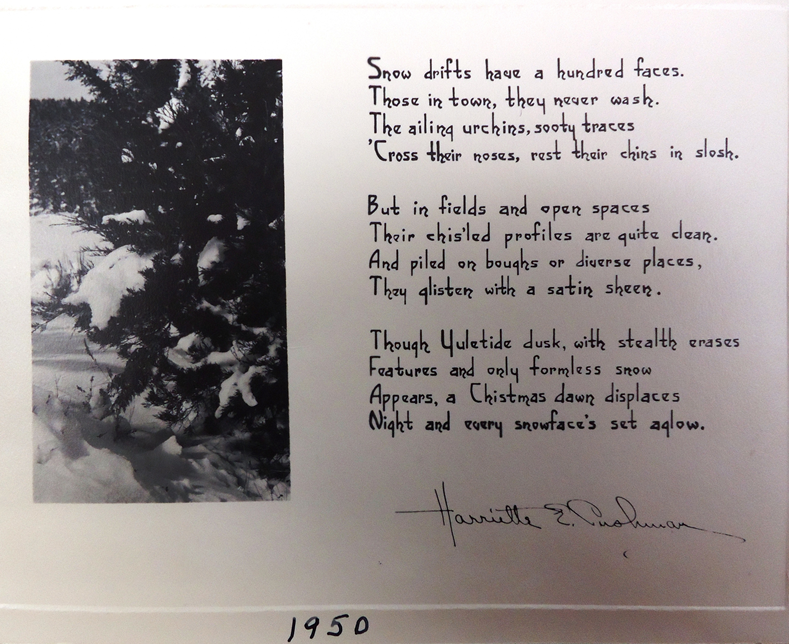

With her extensive travelling Cushman met hundreds of people and she added them to her Christmas card list, which at the time of her death totaled almost six hundred. With a list that long, she devised a card that included either a photograph or drawing she had created along with an original poem.

Although her passion for writing did not end up being her career, she continued to write whenever she could and dedicated most of her time to it after she retired. She was an active and founding member of the Bozeman Montana Friends of the Library, serving as chairperson for four years. She was also a charter member of the Montana Institute of the Arts (MIA) in 1948 and held several offices within the organization including president, secretary and treasurer and served as chairperson of its sections in writing, poetry and history. Cushman participated in the Bozeman MIA Writers Group and won several prizes for her poetry and short stories. She was a two-time recipient of the Mary Brennen Clapp poetry award and won first-place in the MIA poetry contest six times and won the MIA fiction/short story contest three times. In 1960 she was granted a Fellow Award from the Montana Institute of the Arts, its highest award. Cushman was widely recognized as a leader in the poultry industry and also won several awards for her work and service. Although she had great pride for her professional achievements, her love was writing and it consumed whatever free time she had. Her poetry and short stories allowed her to express her inner thoughts and revealed another aspect of her intellect. She wrote her entire life, having a short story accepted for publication when she was in the hospital ten days before she died.

[1] “Letter to parents,” February 28, 1924, Billings, Montana, Box 2, folder 1. Harriette Eliza Cushman Papers, 1893-1978, Collection 1253, Special Collections, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana. Hereafter cited as Cushman papers.

[2] “Letter to parents,” February 22, 1932, Helena, Montana, Box 2, folder 9. Cushman papers.

[3] Merrill G. Burlingame Papers, 1880-1900, Collection 2245, Box 41, folder 18. Special Collections, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana. (Hereafter cited as Burlingame papers).

[4] “Letter to Parents,” March 1, 1931, Bozeman, Montana, Box 2, folder 8. Cushman papers.

[5] “Letter to parents,” February 2, 1921, San Francisco, California, Box 1, folder 8. Cushman papers

[6] “Letter to parents,” April 23, 1923, Billings, Montana, Box 1, folder 10. Cushman papers.

[7] “Letter to parents,” August 25, 1943, Billings, Montana, Box 6, folder 2. Cushman papers.

[8] “Letter to parents,” February 27, 1925, Plains, Montana. Box 2, folder 2. Cushman papers.

[9] Burlingame papers, Box 41, folder 18.

[10] Montana Extension Service, “Report of the State Extension Poultry Specialist, 1935,” 51. Accession 00021, Box 87, folder 47 Montana State University Archives, Bozeman, Montana. (Hereafter cited as Annual Report).