Call for Presentations and Papers

Gendered Advocacy and Activism, Shaping Institutions and Communities

Rural Women’s Studies Association Triennial Conference

Hosted by Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, Arkansas, USA

May 15-19, 2024

Recent challenges to civil rights in various locations internationally bring to mind equity in rural communities which has a separate set of challenges to those of urban areas. Yet, historically activism rooted in rural areas can result in broader change on both regional and national levels. Challenges activists face in pursuing change include a conglomeration of isolation, underfunded education, failing infrastructures, geography, poverty, demographics, lack of health care, low employment, and low wages. Rural activists then require focus and approaches that address their specific needs. In Worlds Apart, attorney and civil rights advocate, Angela Glover Blackwell stated, “equity is the antidote to the plight of isolated, disinvested communities…including rural communities.” Do activists focus on equity as a goal?

In consideration of recent events and movements, the theme of the 2024 Rural Women’s Studies Association conference, Gendered Advocacy and Activism, Shaping Institutions and Communities, emphasizes the central role that women and individuals of all genders and sexualities have played and continue to play in shaping and reforming our institutions and communities. This potentially includes the exploration of such subthemes as: advocacy, education, agriculture, health, reproductive rights, mental health, LGBTQIA+, politics, poverty, race, ethnicity, religion, and Women’s Rights issues.

Founded in 1997, RWSA is an international association for the advancement and promotion of research on rural women and gender in a historical perspective. RWSA welcomes academic scholars, public historians and archivists, graduate students, and representatives of rural organizations and communities to be association members and conference participants.

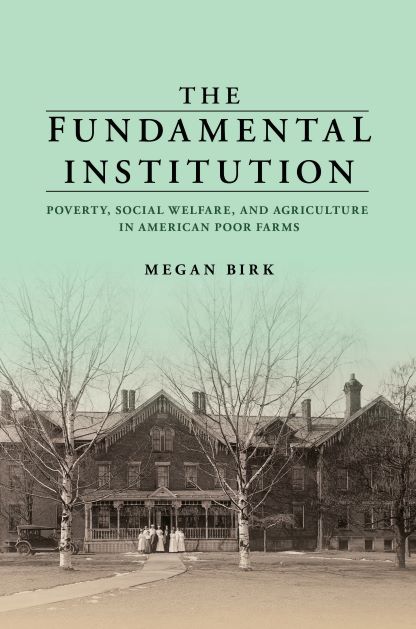

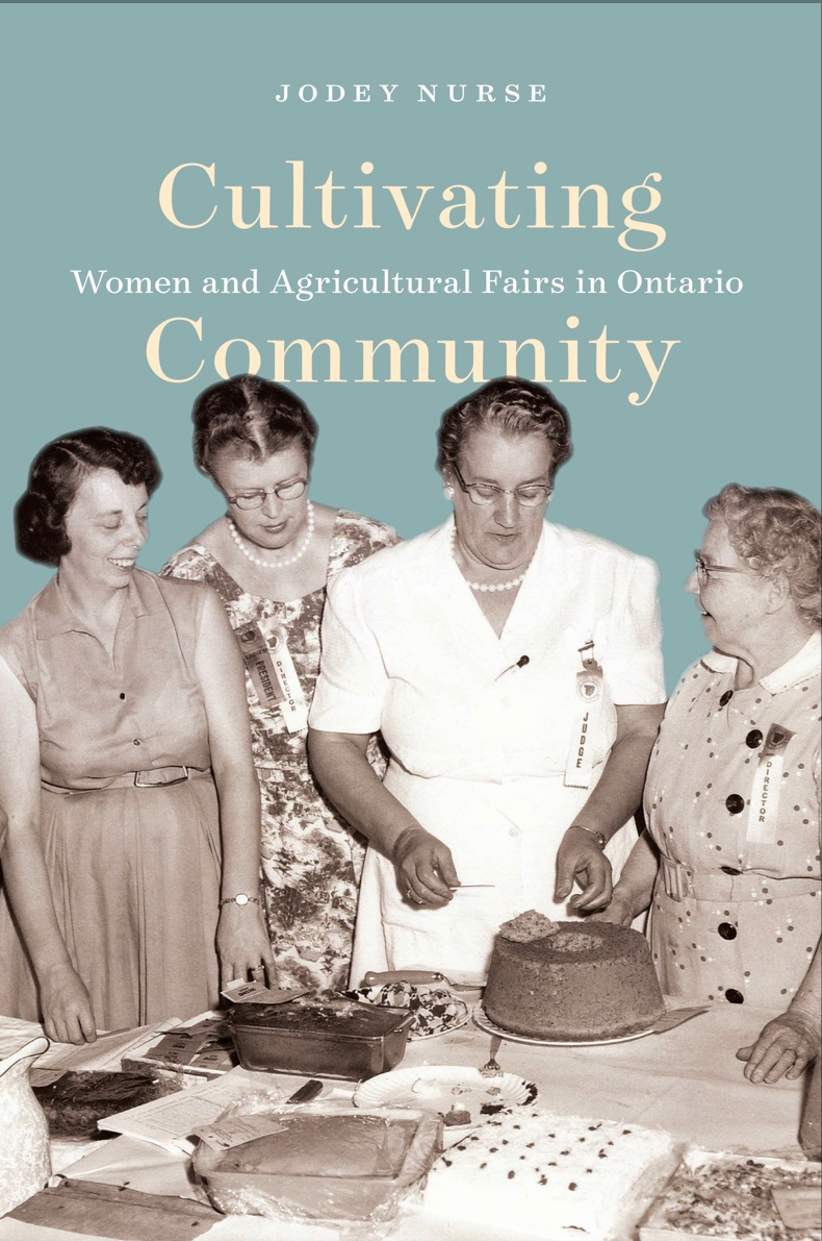

RWSA promotes and advances farm and rural women’s/gender studies from a historical perspective by encouraging research, promoting scholarship, and establishing and maintaining links with organizations that share these goals. Worldwide, the association aims to encourage research, to promote existing and forthcoming scholarship, and to establish and maintain links with contemporary organizations around the interests of rural women, rural communities and the rural environment, including farming and the agricultural sector, from a gender perspective. RWSA welcomes public historians and archivists, graduate students, and representatives of rural organizations and communities as conference participants and members, in addition to academic scholars from diverse fields, including sociology, anthropology, literature and languages, Indigenous Studies, visual and performative arts, and history.

Presentations take many forms at this RWSA conference. Possibilities include workshops, panel sessions, interactive sessions, roundtable discussions, poster presentations, open-mic discussions, performances, readings, and audiovisual presentations.

The theme, Gendered Advocacy and Activism, Shaping Institutions and Communities, encourages exploration of several sub-themes:

- Grassroots activism

- Advocacy

- Women’s rights, including reproductive rights

- LGBTQIA+ rights and identities

- Health, including mental health

- Education

- Politics

- Environment

- Race and ethnicity

Other presentations or papers on any other topic related to rural women/gender/sexuality are also welcome.

Please submit the following information by 1 June 2023:

1. Title of paper/session/workshop/performance (working title is acceptable).

2. 250-word description/abstract of paper or proposed session/workshop, etc.

3. Brief vita/biography of presenter or session participants, and complete contact information for all.

4. Indicate whether or not you grant permission for RWSA to publish your description or abstract on the RWSA blog.

Most concurrent sessions will be 90 minutes. Past sessions have typically included three presentations followed by discussion. If your proposed session diverges from this standard format, please indicate that in your proposal.

We will notify all applicants whether or not we can accommodate your presentation or session by October 2023.

Submissions should be sent electronically to: rw******@gm***.com .

If it is not possible to send your proposal electronically, please send by regular mail to the following address if you are submitting from the Americas:

Cynthia Prescott

Department of History and American Indian Studies

University of North Dakota

221 Centennial Dr., Stop 8096

Grand Forks, ND 58202-8096

USA

Submissions by post from elsewhere in the world should be sent to:

Tanya Watson

24 Owentarglen

Rivervalley, Mallow, Co. Cork, P51WR2E,

Ireland.

For information on travel grants and letters of invitation, contact Cherisse Jones-Branch at cr*****@as****.edu .

For additional information on the RWSA, please go to the organization website, http://www.ohio.edu/history/rwsa/.